OTTAWA—Mired in the worst economic downturn since the Great Depression, the Bank of Canada cited exceptionally high uncertainty for not being able to pinpoint forecasts for economic growth or inflation in its quarterly projections released April 15.

“The outlook is too uncertain at this point to provide a complete forecast,” according to the BoC.

Bank of Canada governor Stephen Poloz said to do so would be “false precision” in his opening statement at the central bank’s press conference.

The bank provided a range of outcomes for gross domestic product (GDP) and inflation, saying that “the timing and strength of the recovery will depend heavily on how the pandemic unfolds and what measures are required to contain it.”

In a departure from its usual quarterly monetary policy report (MPR), the BoC analyzed best- and worst-case scenarios to arrive at ranges for GDP and inflation. It estimates the economy to shrink about 1 to 3 percent in the first quarter of 2020 and 15 to 30 percent in the second quarter from where it ended 2019.

“These estimates suggest that the near-term downturn will be the sharpest on record,” stated the bank.

“Things are so up in the air … we’re almost flying blind,” Steve Ambler, economics professor at Université du Québec à Montréal, told The Epoch Times. Even if forecasts are always wrong, they are still useful, he said.

“It’s just a complete change of style, tone, content, everything else,” Ambler said. “Monetary policy per se is on hold for the time being.”

The BoC expects inflation in consumer prices to fall to close to 0 percent overall in the second quarter, but said some items may rise in price due to lack of supply and a weaker Canadian dollar, which raises the price of imports. The drop in gas prices and in demand more generally “can be expected to dominate in the overall measure of inflation.”

The BoC expects inflation in consumer prices to fall to close to 0 percent overall in the second quarter, but said some items may rise in price due to lack of supply and a weaker Canadian dollar, which raises the price of imports. The drop in gas prices and in demand more generally “can be expected to dominate in the overall measure of inflation.”

Even with unprecedented government support to businesses and households and with the central bank printing money to buy debt and support financial markets, the BoC doesn’t envision inflation spiking. Instead, its scenario analysis shows the risk of prices falling or stagnating as being more likely until at least 2022.

“If you want to stimulate demand in the current circumstances, you basically can’t,” Ambler said. “Large sectors of the economy are in forced lockdown. Traditional monetary policy really can’t stimulate demand in any meaningful sense.”

Poloz pointed to China as a possible example of how consumer demand might recover more slowly than the supply side of the economy. People may start going to work but demand for entertainment and travel could still languish.

“The demand is the thing that could fall short of supply during that recovery phase,” Poloz said, adding that people need to be talked into the recovery.

Ambler said some components of consumer prices are essentially irrelevant now—like travel—but that food prices could spike due to shortages caused by supply chain problems and even a lack of temporary workers to help in farming.

Wide-Ranging Forecasts

The uncertainty around the size of the hit to Canada’s economy in 2020 and around the expected rebound in 2021 is leading to disparities among other forecasters.

On April 14, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) projected that the Canadian economy will fall 6.2 percent in 2020 and then rebound by 4.2 percent in 2021.

BMO estimates that every week of shutdown costs the economy between 0.5 to 0.7 percent of annual GDP. The Bay Street bank forecasts that the Canadian economy will shrink 4.5 percent in 2020—notably worse than the previous biggest drop of 3.2 percent in 1982, but not as dire as the IMF’s projection. BMO forecasts a strong 6.5 percent rebound in 2021.

TD Securities’ forecast is 0.8 percent higher than BMO’s, at -3.7 percent for 2020 with a weaker 2.3 percent rebound for 2021.

The BoC noted that prior to the pandemic, the Canadian economy was in good shape, aside from the energy sector and high household debt levels, and that this resilience will aid in the eventual recovery.

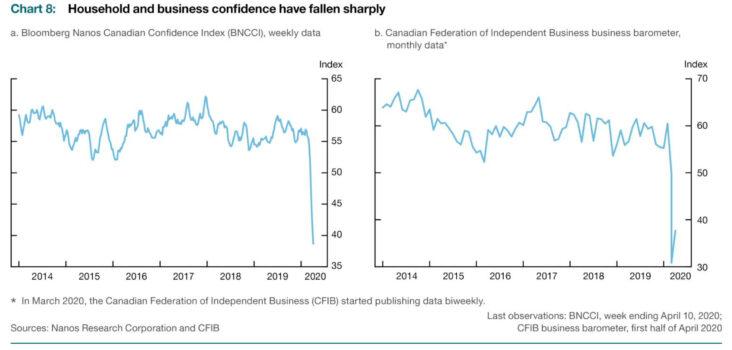

But business and consumer confidence has fallen sharply due to the uncertainty of the duration of the outbreak, and that affects their spending habits.