Other experts, too, are increasingly wary of engaging with scientists from China.

“There have been other [protest] cases associated with analysis of genetic data, especially in the context of surveillance and/or identification,” according to professor Margaret Kosal, who holds numerous appointments, including at the Georgia Institute of Technology and the Parker H. Petit Institute for Bioengineering and Bioscience.

“For my work dealing with security implications of emerging and disruptive technologies, these studies are some of the most specific, scientific-based, documented open-source exemplars of use of genetics and machine learning [ML] algorithms by [the] PRC [People’s Republic of China] and indicators of capability. I wrestle ethically with questions of in what context, or even if, I should use [for example, cite and reference] them in my own research writing and speaking.”

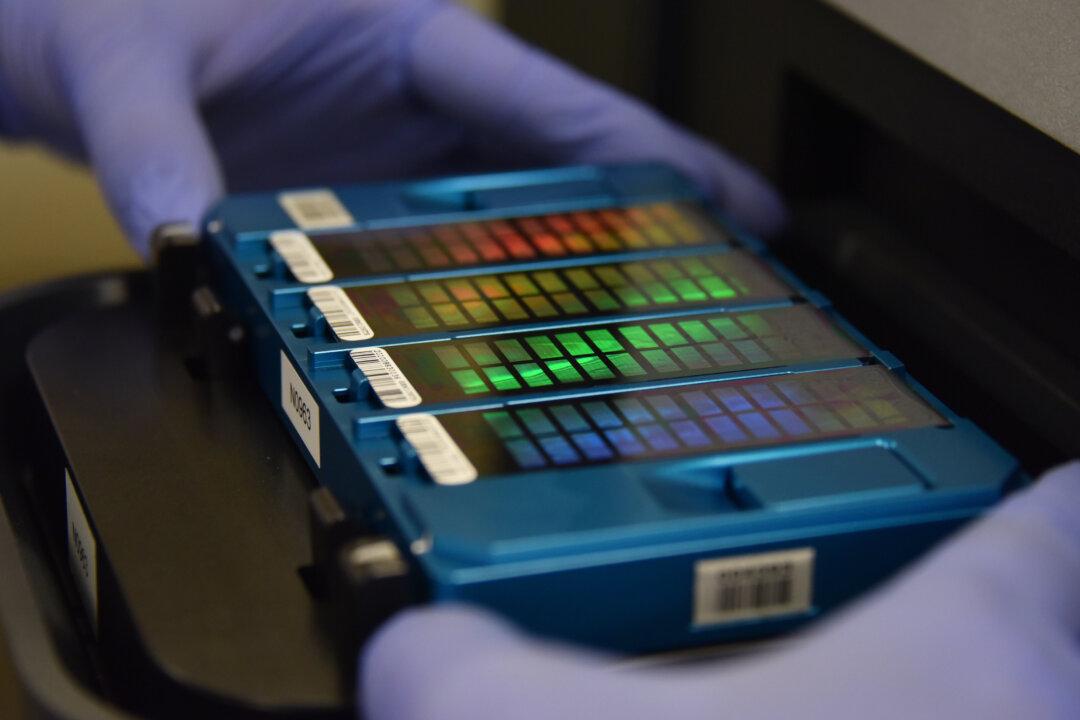

Curtis stated: “We know that forced organ harvesting is occurring [in China]. We know that people are subject to arbitrary arrest, to detention, sometimes to disappearances—sometimes without judicial process. The third thing we know, and this is more recently, is that there is … mass genetic testing across whole populations, minority populations, and particular regions.”

He said that “people are sometimes subjected to medical examinations, they provide blood samples, and one of the things that are done with these blood samples is that one can take DNA from them.”

But China’s DNA collection was previously focused on minorities, and according to Curtis, it allows the Chinese authorities to maintain a data bank of potential organ donors, who could be forced into organ donation.

There is a relative lack of voluntary organ donations in China and mass DNA collection is also opposed in the country. Human rights organizations argue that there is no real consent to DNA collection in a highly authoritarian system where it is difficult to decline. They are also concerned that widespread DNA testing could be used to punish family members of dissidents and activists.

According to The New York Times, police officers in China have demanded blood samples in mass DNA testing of male children in schools. It cites another case in which a 31-year-old male was forced to give a blood sample after being threatened. Mr. Jiang, a computer engineer from northern China, told the Times in a 2019 interview that authorities warned him, “If blood wasn’t collected, we would be listed as a ‘black household.’” If he failed to comply, it ”would deprive him and his family of benefits like the right to travel and go to a hospital,” the report said.

Given the nature of the regime in Beijing, Curtis said: “It is very hard to see why that [forced organ harvesting based on mass DNA collection] would not be happening. Here you have a regime that is collecting samples … from which they can get DNA from all of these people. We know that they have no compunction about arresting people, detaining people. We know that they have no compunction about forced organ harvesting. That brings a uniquely terrible new dimension to this process.”

Curtis argued that the pool of potential donors for forced organ harvesting has expanded in China from executed prisoners, convicted prisoners, to detainees in general. And now Chinese “authorities can go through the DNA banks that they have. They can identify a suitable donor. ... It does not have to be a detainee, because it can be someone just walking on the street, going to work, going to school, at home. There could be a knock on the door, and that person can be detained, taken from their home, taken from their workplace—never seen again because they are a good match for somebody who needs an organ transplant,” he said.

This creates the potential for the entire population of China to be a “human farm of potential organ donors,” according to Curtis, who stressed that there is no evidence of this. But he said: “We do have evidence that forced organ harvesting is happening. We do have evidence of arbitrary detention and people disappearing. And we do have evidence that there is massive DNA collection going on.”

He asked, “Why would the Chinese authorities not engage in forced organ harvesting from Tibetans, Uyghurs, and prisoners, for example, who have their DNA stored in a bank, if a powerful CCP official needs a kidney transplant, and therefore needs to find a good match?”

Curtis said that if gene banks are used for transplants that utilize forced organ harvesting, then “this does not only involve security services.” He continued, “For this to work, doctors have to be involved, genetic sciences and a lot of other people” in a professional scientific and medical network.

Unlike in Britain, where scientists would go to jail for involvement in such unethical medical practices, there is no professional transparency and accountability in China, he said. “There is no mechanism to go up against the state and advocate to uphold an ethical standard if it goes against what the state wants to do.”

Given what he knew about forced genetic testing and forced organ harvesting, Curtis felt increasingly uncomfortable, as editor of a genetics journal, about submissions he received from China. “Why should I trust that the scientists had carried out their research in an ethical way, when I know that the [Chinese] scientific establishment and medical establishment is willing to put up with practices such as this?”

Curtis explained, “What this brings us is a new genetics dimension to this problem.” He said that we should be doing something about this. “I think there is a way that we could seek to influence China’s behavior,” he said. “There are places where there are sensitivities and things that they care about and one of these things is their scientific recognition, and the careers of those in their sciences.”

Curtis raised the question of the routine rejection of scientific papers based on their origin in China. He did this when he was editor of the Annals of Human Genetics, which is based at UCL and published by Wiley.

Curtis, Schulze, Yves Moreau at KU Leuven ESAT-STADIUS in Belgium, and Thomas Wenzel at the Medical University of Vienna in Austria, attempted to publish the letter, titled “China—is it time to consider a boycott?” elsewhere.

The proposal to reject all articles from China contradicts rules frequently found in non-discrimination clauses against discrimination based on national origin. But this is a misguided inclusion when some nations are committing crimes against humanity and genocide, according to the U.N. definition.

Not allowing such discrimination, especially against the world’s most powerful totalitarian state, invites the further growth of its power. Failing to take measures against this state’s genocide and crimes against humanity is to fail to take a stand against these greatest of injustices. Should we not discriminate against genocide? Is non-discrimination in this case not complicity in an exponentially greater discrimination?

Other journals refused to publish the letter, including the Lancet, the British Medical Journal (BMJ), and the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA).

Curtis explained in an email: “According to my contract I had sole responsibility for what was published and I could have simply rejected every submission from China. But I knew this would not be in keeping with what was expected of me. It would not accord with the policies of the publisher and it was also something that the editorial board did not support (it was discussed with them). I realized that it was a personal position that I was taking and so I decided to resign.”

The Annals of Human Genetics was originally called the Annals of Eugenics, the disgraced scientific field of “improving” the human species through breeding out supposed traits of mental illness, criminality, or in the case of Nazi Germany, racial characteristics.

The case of Curtis unfortunately demonstrates that the most ethical of scientists, in fields sometimes lacking in ethics, are the ones forced out of positions of salutary influence.

Curtis continues his work on bringing a more ethical approach to the genetics field, however, both through speaking out publicly against forced genetic collection and forced organ harvesting, and in raising questions about whether a formal medical scientific boycott of cooperation with China should be instituted.

“What that would mean for scientific journals is that we would not consider submissions coming out of China, coming from Chinese doctors and Chinese scientists,” he said. “We would be saying, look, you know your profession is complicit in these practices. We are not going to treat you as our colleagues. We are not going to say that we know that you follow the same ethical practices that we do.”

Curtis argued that this would raise awareness in China’s medical and scientific communities about unethical practices. He wrote in an email, “We are hoping to soon launch a website that will allow doctors and scientists to sign up to a boycott.”

Just after Curtis spoke at the summit, the coalition of five nonprofit groups that organized it, Doctors Against Forced Organ Harvesting (DAFOH) in the United States, CAP Freedom of Conscience in France, the Taiwan Association for International Care of Organ Transplants, the Korea Association for Ethical Organ Transplants in South Korea, and the Transplant Tourism Research Association in Japan, released their “Universal Declaration on Combating and Preventing Forced Organ Harvesting.”

Its Article 9 is directly supportive of Curtis’ proposal, among other prescriptions. It states, “All governments shall (1) urge medical professionals to actively discourage their patients from going to China for transplant surgery; (2) urge medical professionals not to give training in transplant surgery or not to provide the same training in their countries to Chinese doctors or medical personnel; (3) urge medical journals to reject publications about the ‘Chinese experience’ in transplant medicine; (4) not issue visas to Chinese medical professionals seeking training in organ or body tissue transplantation abroad; [and] (5) not participate in international seminars, symposia or conferences of Chinese doctors in the field of transplantation and transplant surgery.”

We do in fact need not only a scientific and medical boycott of China, as Curtis has mooted, but legislation banning scientists and medical professionals from cooperating with foreign medical and scientific establishments that are engaged in highly unethical practices. This applies as much to the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) today, as it should have applied to Nazi Germany in the 1930s and 1940s.

With such legislation, awareness would be raised that the West is serious about its commitment to human rights and its willingness to energetically assert these rights in the face of the overwhelming power of illiberal political parties like the CCP. Awareness would be raised in China, where constraining effects of the law would provide consequences for the CCP’s support and leadership in unethical medical and scientific practices, thus pressuring it to cease forced DNA collection and forced organ harvesting. We must take these issues with the utmost of seriousness in countries that are privileged to enjoy their freedoms, as in the case of the Falun Gong, Uyghurs, and Tibetans in China, they are constitutive of genocide.