Many China observers believe the 10,000-strong gathering of Falun Gong practitioners outside Communist Party headquarters in Beijing 20 years ago this month was the catalyst for the massive suppression unleashed soon after.

In fact, it was a peaceful and orderly appeal despite the large numbers, but it was portrayed by the authorities as laying siege to the central government and used as an excuse to launch a relentless persecution campaign against Falun Gong.

The purpose of the gathering on April 25, 1999, was actually to petition the regime to grant the non-political practice legal status and stop harassing its adherents.

The harassment had started as early as June 1996, when the Propaganda Ministry instructed various levels of government to criticize the practice. Later, Falun Gong books were prohibited from being published or distributed, and police in regions across the country had begun to seize books from practitioners and interfere with their group practice sessions.

Then, a national magazine based in the coastal city of Tianjin published an article slandering Falun Gong, a traditional meditation practice also called Falun Dafa that had 70-100 million adherents by the late 1990s, according to a government survey

This greatly troubled practitioners, as the article had a negative effect on the practice, so some called and wrote to the magazine to request the false report be corrected, while many others went to Tianjin to try to redress the issue in person.

On April 23, riot police came to disperse the practitioners using clubs and high-pressure water cannons, and 45 were arrested. This, in turn, caused practitioners to go to appeal at the Tianjin Municipality. There, officials told them to take their concerns to the State Council Appeals Office on Fuyou Street in Beijing.

“We cannot take responsibility for this matter. Go to Beijing, the Ministry of Public Security already knows about this,” an official said, according to Minghui.org, a website that compiles information on the Falun Gong persecution.

Word spread rapidly through the Falun Gong community, and in good faith, thousands of practitioners from Beijing and other parts of the country made their way to the appeals office, in what was to become the largest spontaneous public gathering since the 1989 student protests on Tiananmen Square.

In Silent Protest

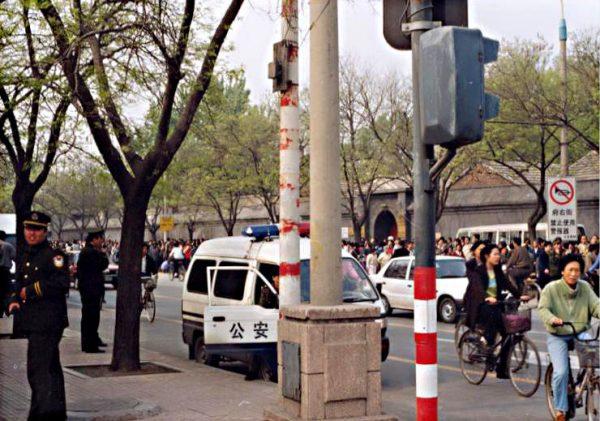

When practitioners began arriving on Fuyou Street early on the morning of April 25, some 1,000 public security personnel and plainclothes officers had already been deployed.Some of the officers were talking on their radios, and some were corralling practitioners toward a designated area. When the practitioners approached the appeals office, some were directed across the street to Zhongnanhai, a complex of buildings that serves as the headquarters of the Chinese Communist Party and the central government.

This put them in a position of surrounding Zhongnanhai. In fact, this tactic was a calculated move that was later used to falsely accuse the crowd of and “encircling” or “besieging” the central government in a threatening way.

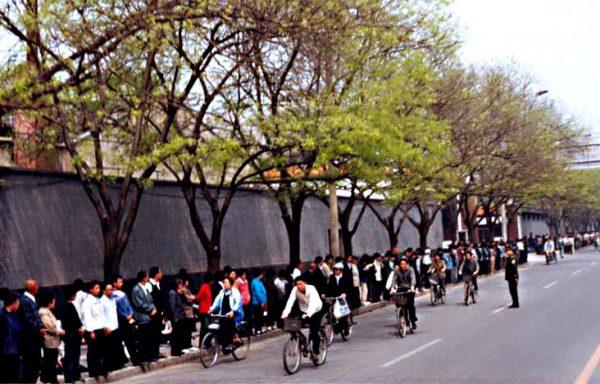

Images captured by ABC showed an orderly assembly of people of all ages stretching for about two kilometers along the tree-lined sidewalks of Fuyou Street and some side streets. Some practiced the slow-moving Falun Gong exercises, while others sat or read. Ample room was left for pedestrians to pass, and the flow of traffic wasn’t interfered with; however, police closed the street to traffic soon after the crowd gathered.

There was no shouting of slogans or waving of banners—in fact, by all accounts the practitioners took pains to be as unobtrusive as possible, even bringing along bags to hold any litter that might be dropped.

“No record, film, or plausible account suggests that the Falun Gong practitioners did anything even faintly provocative during the entire episode, which continued for 16 hours. No littering, smoking, chanting, or speaking to reporters,” writes author and China analyst Ethan Gutmann in the article “An Occurrence on Fuyou Street.”

Those gathered had three requests: release the arrested Tianjin practitioners; allow Falun Gong practitioners a non-hostile environment in which to practice; and lift the ban on publishing Falun Gong books.

A few of the practitioners who gathered at the appeals office were invited inside to speak with then-Premier Zhu Rongji; Zhu later issued an order to release those arrested in Tianjin. Around 9 p.m., a message was passed around among practitioners that the issues were basically resolved and that they could leave.

The crowd dispersed as quietly as they had come, unsuspecting that much greater troubles were lurking on the horizon.

Terror Campaign Begins

Three months later, on July 20, Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leader Jiang Zemin illegally outlawed the practice in a move to consolidate his personal power as well as calm the turmoil occurring within the Party at the time.Jiang used the events of April 25 to “prove” that Falun Gong was both organized and an immediate political threat. But in fact, he had decided to ban the practice before the appeal: he had already established the 6-10 Office—an extralegal, secretive, Gestapo-like organization—to oversee all aspects of the persecution campaign.

All he had to do now was convince the Communist Party Politburo. In a letter to the Politburo written the night of the demonstration and openly published in 2006, Jiang described Falun Gong as a nationwide religious organization with a worldview inimical to that of communism and Marxism. The CCP does not allow nongovernmental organizations to exist beyond its watch; describing Falun Gong as one made it a valid political target.

An hour-long film depicting the demonstration as a terrorist act was released, and state media launched a propaganda blitz portraying the event as a riot.

Gutmann said the allegation that the appeal posed a threat to the regime comes down to blatant Party propaganda, but it is a notion that Western media ran with.

“Because the Western media know so little of Falun Gong, this fiction survives in accounts of April 25. … It is repeated in scholarly works on Falun Gong history, and is regarded almost as the movement’s original sin,” he writes.

“The idea that Falun Gong besieged Zhongnanhai in a threatening way is a direct transmission of the Communist-party line. … Whatever you call the demonstration, it was not specifically targeted at Zhongnanhai, much less was it a siege of the compound. Regardless, for the Chinese audience that Falun Gong is trying to reach, the Party still owns the language and the history.”

The brutal persecution initiated by Jiang was the beginning of a new communist terror campaign the likes of which had not been seen since the Cultural Revolution, and one that has left untold death and suffering in its wake.

“The crackdown was justified with the myth of a day of infamy—April 25—a fiction concocted as a pretext to stage an unprecedented persecution, one that continues to this day,” Gutmann writes.

“April 25, then, was simply the unfolding of an elaborate bait-and-switch, with Falun Gong as the patsy.”