SYDNEY–Australian Aborigines, among the oldest continual inhabitants of their land in the world, have long been depicted as hunters and gatherers. Mounting evidence, however, suggests they were not primitives but sophisticated cultivators and land managers.

Researcher and author Bruce Pascoe, a Bunurong man from south eastern Australia, searched the accounts of early explorers and settlers for evidence of cultivation and was astounded at what he found.

“I came across repeated references to people building dams and wells, planting, irrigating and harvesting seed, and manipulating the landscape,” he said.

One of the most vivid accounts was from explorer Charles Sturt, who was the first European to penetrate the interior and see the Simpson Desert.

In his 1844-1846 expedition, Sturt was near death, having already lost some of his exploration party, when he came across a group of some 400 Aboriginals.

They saved his life by giving him water, roast duck and cake which had been made from their own grain, Mr Pascoe said. Sturt repeatedly described the cake as the “best cake he had ever eaten”, even after his hunger had been satiated.

“He describes it in great detail, he describes the method of the milling, the flavour, and he even goes as far as to give a short recipe,” Mr Pascoe said in a phone interview.

“They still call it ’the dead heart of Australia' and here he was eating cake made from flour harvested there.”

In another account, explorer and government surveyor Thomas Mitchell describes riding through nine miles of grain crops in his 1830s exploration of black soil country in northern New South Wales.

“Not only had the grain been cut, but it had also been stooped. It had been put into bales throughout this landscape in readiness for threshing,” Mr Pascoe said.

Mr Pascoe, who has written a book, Dark Emu, detailing his findings, says he now believes describing Aborigines as nomadic hunters and gatherers is “a misnomer”.

Aborigines did move according to season and for cultural activities, he says, but many had permanent abodes, with some even maintaining two or three houses. After European occupation, however, their crops would have been destroyed and many would have been forced from their land, giving the appearance of wanderers.

Intensive Cultivation

Mr Pascoe is not alone in his views. Dr Beth Gott, a botanist at Monash University, manages an aboriginal garden at the university and runs courses on aboriginal plants. Her specific area of interest is the yam daisy, or murnong, whose tubular root was the staple food source of Aboriginal communities in Victoria.

Early explorers have described fields of murnong that looked like pastures, she says. Those fields then became major grazing areas for early sheep flocks that quickly decimated the crop.

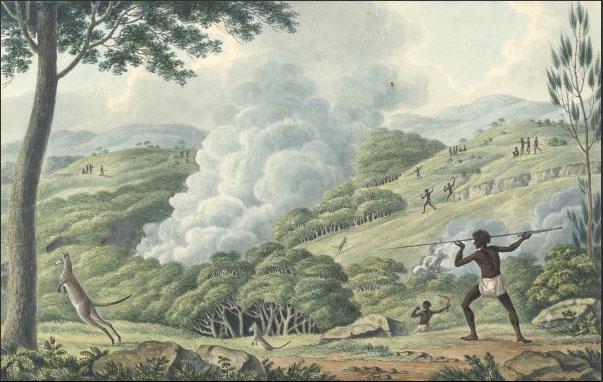

Dr Gott says Aboriginal groups practised land management to cultivate the murnong, which requires a lot of sunlight to thrive. They would burn around the murnong crop on a rotational basis to keep taller plants from dominating, while also fertilising the ground. The burning did not harm the root and was timed when the leaves browned.

“They knew when to burn and to define the burn exactly where they wanted it, eventually producing a mosaic across the countryside in various stages of fire recovery,” Dr Gott said.

Many other plants were cultivated in Australia, including rice – of which there are at least four native varieties – and rock lilies. Dr Gott noted that sustainable farming practices were evident.

The tubers of murnong for example were harvested without destroying the plant; the “grandmother” and the “child” tuber were left while the “mother” was gathered based on its edibility.

“They took care of the plants within the environment in which they grew,” she said.

With occupancy evident some 45,000 years ago, the Australian Aborigines had learned to do what was needed to ensure their survival.

“If they hadn’t done it, they wouldn’t have eaten,” Dr Gott said.

A Single Estate

History professor Bill Gammage believes Aboriginal communities worked as much as they could with the natural environment but ultimately shaped it considerably.

“Where it suited they worked with the country, accepting or consolidating its character, but if it didn’t suit they changed the country, sometimes dramatically, with fire or no fire,” he wrote in an article on the academic website, The Conversation.

Dr Gammage revisited the early records of Australian explorers and artists, as wells as later researchers, who identified extensive land management techniques. He documented his findings in his book The biggest estate on Earth: How Aborigines made Australia.

While it was thought that pastoral scenes of early Australia were presented by early settlers through a romantic lens, it now appears that they were describing exactly what they saw, he says.

Areas of grassland were established to attract animals for easier hunting while areas of bush and trees were maintained to provide shelter for them.

“Feed-shelter associations (‘templates’) must be carefully placed so as not to disrupt each other, as this would make target animals unpredictable and the system pointless,” Dr Gammage said.

“Given how long eucalypts live, templates might take centuries to set up. Each needed several distinct fire regimes, continuously managed and integrated with neighbours, to maintain the necessary conditions for fire-stick farming.”

Dr Gammage believes the system could only work if all groups were a party to it and concludes that it would require continent wide coordination.

“This system could hardly have land boundaries. There could not be a place where it was practised, and next to it a place where it wasn’t. Australia was inevitably a single estate, albeit with many managers ,” he wrote.

Mr Pascoe says he was familiar with Aboriginal aquaculture and irrigation systems but it has taken time to get his head around the scale of land cultivation.

The amount of cooperation across such a huge area and with so many different groups would require a very strong system of governance.

“It had to be very, very powerful in order to convince young people that this was the way to go,” he said.

“Most other civilisations had various levels of dissent from time to time but here it seems there was a consensus on how to manage the land and the people.”

Mr Pascoe says he has received many calls from Aboriginal people recalling cultivation activities and stories. He expects further research will substantiate his claims.