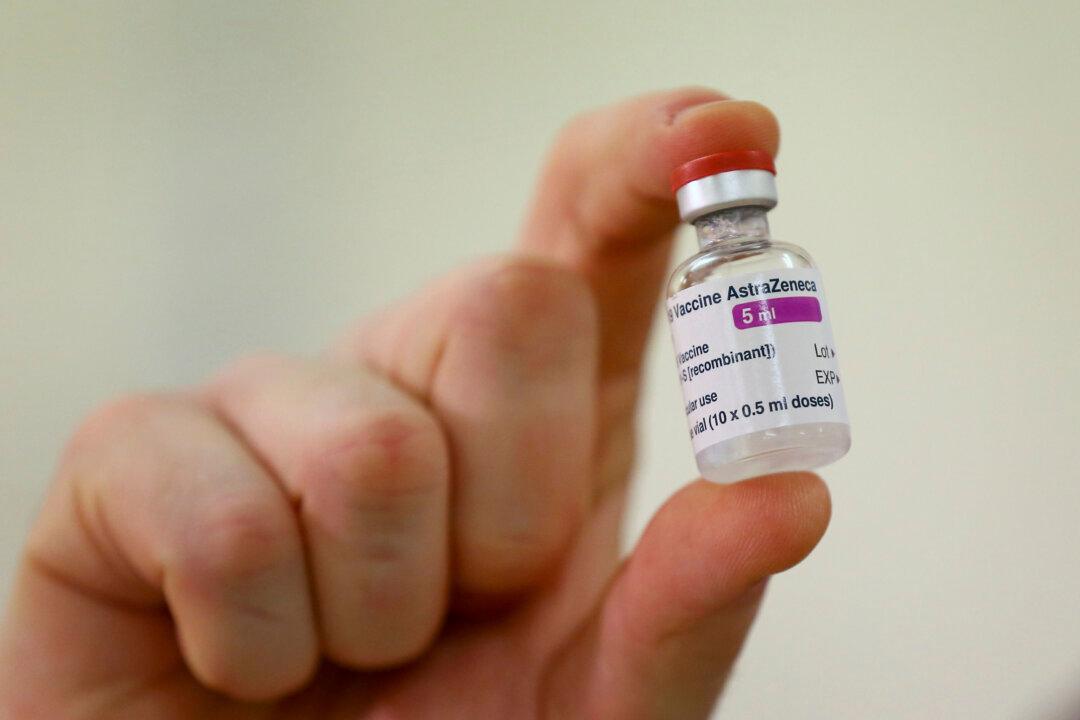

AstraZeneca and Oxford University aim to have an updated vaccine to address the different CCP virus variants by the autumn, according to an executive for the UK-based drugmaker.

Research chief Mene Pangalos said they wanted a next-generation vaccine “as rapidly as possible” to tackle new variants of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) virus, commonly called the novel coronavirus.