What does it say about our society when one hedge fund manager makes a bigger income than the whole population of Springfield, Ohio, or Burbank, Calif.?

A population of 100,000 is substantial. Five states don’t even have one metropolis that large. Some cities that size, like Fargo, N.D., are their state’s biggest. Others, like Lansing, Mich., are state capitals.

About 100,000 people live in Rochester, Minn., home of the Mayo Clinic. The same goes for Burbank, Calif., and Springfield, Ohio.

Most of America’s cities of 100,000 now share one uncomfortable reality.

Consider this, Lansing: You work hard. Most of your 40,000-plus households have at least one full-time wage earner or business owner. Many have more than one. Some of your Michiganders work multiple jobs. They teach kindergarten, fight fires, fill cavities, tend to the sick, design software, build websites, unclog drains, and cook and serve countless restaurant meals.

Of course those folks don’t all take home the same paychecks. That’s how our American society is structured. Your compensation is the measure of the value our society places on the work you do.

Rightly or wrongly, America values the work of some folks more than the work of others. We value the work of Rochester’s doctors more highly than the work of the nurses who assist them, for instance.

What value does our society place on the work of all your citizens collectively, Fargo? About $3.5 billion. That sounds like a fortune, Burbank, but remember that you all had to put in over 100 million hours to earn that $3.5 billion.

Remarkably, Springfield, our society places that same $3.5 billion value on the work of just one man.

Meet David Tepper. He raked in $3.5 billion last year for his work. Of course, he likely pocketed additional income from investments in the form of interest and dividends. But for his work alone he collected $3.5 billion in compensation.

That’s right, Lansing. The 100 million hours you put into all of the classes you teach, the fires you fight, the cavities you fill, the restaurant meals you prepare and serve, the cars you repair, the drains you unclog, the illnesses you treat, the crimes you stop, and the lives you save are assigned a total monetary value equal to the work of just one man.

Never heard of this Tepper guy? Would you like to know what he does?

He moves money around. You see, Fargo, he’s a hedge fund manager. The founder of Appaloosa Management takes care of the investments of millionaires and billionaires, deciding when to buy and when to sell, and when to borrow to buy even more assets.

And that work, Rochester, is valued as highly by our society as the work of all your citizens, combined.

Now, consider this, Springfield: Last year, Tepper had to buy 2,190 meals for himself and his ex-wife-to-be from his personal revenue, just like the people of Springfield had to buy over 128 million meals from the same pile of dough. (His three children are in their 20s.)

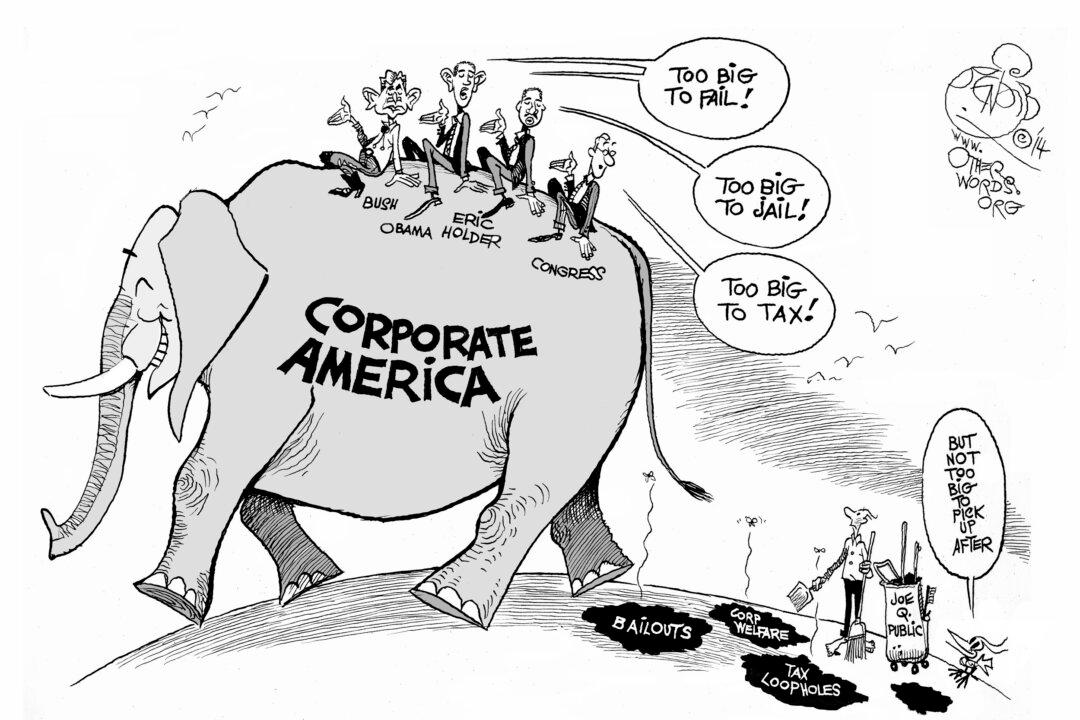

And Tepper’s total tax bill wasn’t appreciably higher than that of all the people of Springfield combined. Our society has decided that it would be a mistake to tax this so-called job creator heavily.

So, Burbank, guess who had more income left last year, after taxes and living expenses—Tepper, or your entire population? That’s right, Mr. T did. And after several years of this, I bet you can guess who will control more wealth.

What does this say about our society’s values?

I have nothing against David Tepper personally. He may be the nation’s highest-paid hedge fund manager, but he’s actually given generously to Feeding America and other charities with his mammoth income. I admire that.

Yet when a society equates the work of one man and the residents of an entire city, has that society lost its way? And when that society taxes the income he could never spend at roughly the same rate it taxes the income on which the people of an entire city depend to feed and clothe their families, has that society gone mad?

Bob Lord, a veteran tax lawyer, practices and blogs in Phoenix, Ariz. He is an Institute for Policy Studies associate fellow. This article previously published in OtherWords.org.