The host nations of major sporting tournaments like the football World Cup are usually obsessed with the international status and prestige that comes with holding these events. However, the impact that these tournaments have on the host society itself is more interesting.

I witnessed first-hand the impact on the 2002 World Cup on South Korea, which it co-hosted with Japan. The heroics of its football team in reaching the semi-finals – the first Asian team to do so – energised the country and restored a national pride battered by a century of occupation, Cold War and authoritarian governance.

In 2014, Brazil approaches the World Cup in a different position. It is the spiritual torch-bearer of world football and an emerging economic power, but also as a nation divided by protests, cost-of-living pressures, socioeconomic inequality and corruption. South Korea 2002 makes for an interesting comparison to explore what this year’s World Cup might mean for Brazilian society.

The South Korea I encountered as an exchange student in 2002 was less vibrant and cosmopolitan than it is today. Its fledgling democracy was barely a decade old. Corruption stemming from its rapid development phase, anti-communist ideological rigidity and social conservatism were the norm.

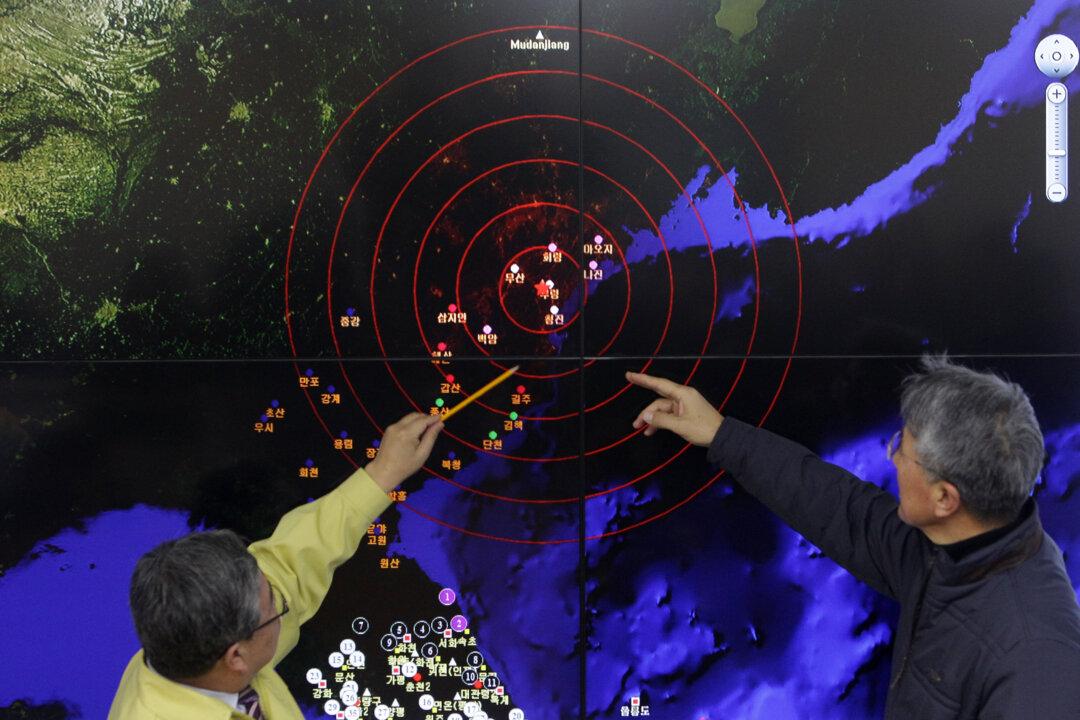

South Korea’s democratic transition was punctuated by traumatic events such as the first nuclear crisis with North Korea in 1994 and the 1997 Asian financial crisis. Rapid economic development had brought material prosperity as well as social uncertainties as established orders began to change.

To a foreign observer like me, South Korea was an insular place, exhibiting elements of both xenophobia and deep-seated and dignified pride. The World Cup changed this negativity in a profound way. A positive national feeling erupted as the country, through its football team, realised it could be more than the plaything of more powerful nations.

To be immersed in this transformation was electric. I will never forget sitting in Busan Stadium for South Korea’s opening match with Poland, awestruck by the stirring sound of 80,000 Koreans chanting “dae han minguk” (Republic of Korea). Nor will I forget the delirium following Ahn Jong Wan’s golden goal in extra time against Italy, and Korea’s penalty shootout quarter-final victory over Spain.

Hundreds of thousands of Koreans took to the streets to support their team, uniting the nation. The tournament provided an outlet for a new South Korea – proud, confident and cosmopolitan – which reflected the country’s ascendance as an important economic, political and social actor on the world stage.

On the surface, the 2014 World Cup and 2016 Olympics should be Brazil’s coming-out party too. Brazil is rich in natural resources, with a rising middle class and solid economic fundamentals. Many Brazilians want to show the world that they are a first-world country, keenly aware that despite their growing economic might, they still do not enjoy developed world status.

Despite the national team being a five-time World Cup winner and perennial tournament favourite, all is not well in Brazil as the cup approaches. Country-wide protests in June last year drew global attention to Brazil’s deep socioeconomic divisions.

Preparations for the World Cup and the 2016 Olympics have emphasised in a highly visible way the corruption and nepotism of the Brazilian business class, along with popular frustration at the inadequacy of basic services, despite high rates of tax. The situation has been further exacerbated by rising land values and costs of living driven by tournament-related urban development.

The protests have also been noteworthy in the way that they have mobilised people across class boundaries to unite against corruption that seems to proliferate with impunity. Proposed legal changes to strip public prosecutors of their investigative powers (PEC37) and give Congress the power to overturn Supreme Court decisions were so breathtaking in their scope that even the most comfortable of Brazilians took notice.

Protest organisers plan to continue their demonstrations through the tournament. Violence between civilians and police in Rio de Janeiro’s favelas has reportedly increased in recent weeks as police attempt to improve security ahead of the tournament.

How well the Brazilian team performs may be a critical factor. In the same way as the South Korean team’s success in 2002 enabled that country to unite and transcend its baggage, so Brazil’s leaders hope success in the coming tournament might relieve some pressure from the protest movement. The pressure on the team to perform is immense.

The ultimate legacy of the World Cup may be more than a series of expensive stadiums. With a national election in October and the Olympics in 2016 to come, the World Cup may be a coming-of-age experience for Brazil, but more so in coming to terms with its internal contradictions rather than the attainment of international status.

Benjamin Habib does not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has no relevant affiliations. This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Thank you to Johannah Hopgood for her assistance with this article.