SAN FRANCISCO—Dr. Maria Rivero had worked for 22 years at the Laguna Honda Hospital. When she discovered a misuse of the patient gift fund money, she decided in early 2010, together with her colleague Dr. Derek Kerr, to blow the whistle about it.

Both had to face the consequences common for many whistleblowers: retaliation.

When Rivero put in her complaint and told her superiors about it, she met a “wall of silence,” and she and Kerr were labeled detractors.

She was harassed and her superiors threatened to fire her. Due to daily pressure, she became anxious and depressed and needed to quit her job a few weeks later to get out of this “toxic environment,” Rivero said.

Kerr was fired, ostensibly due to budget cuts, a few days after he contacted the city’s whistleblower program. He had worked more than two decades at Laguna Honda as a hospice physician.

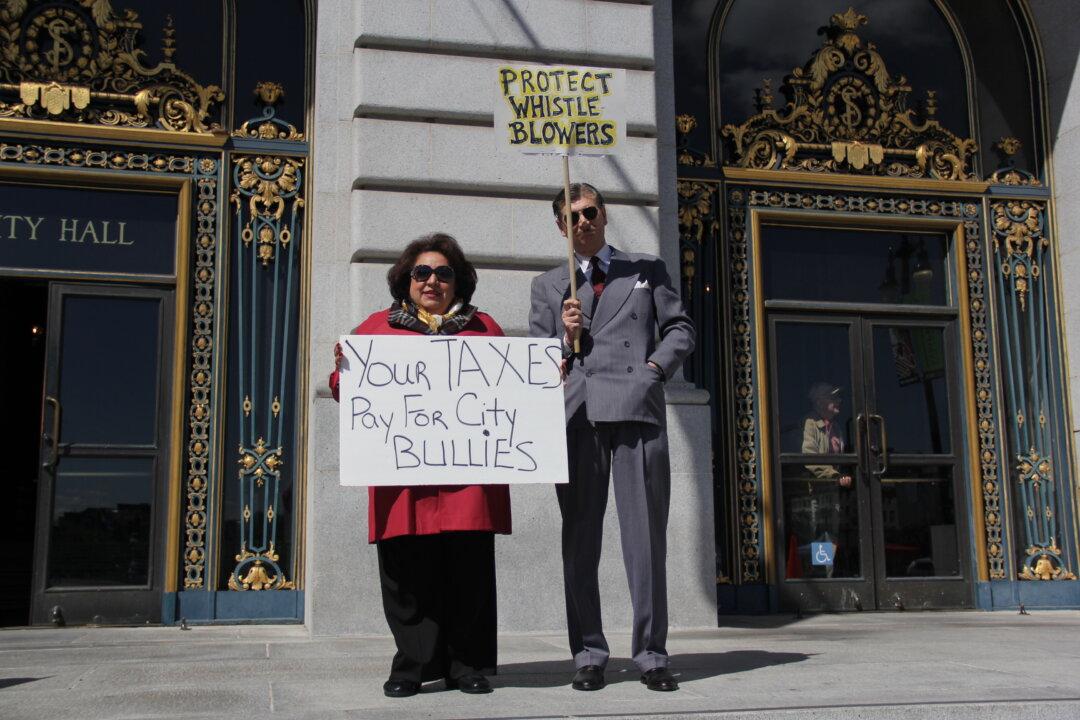

Both Kerr and Rivero attended a rally in front of City Hall on Monday to protest the bullying of city workers and the lack of protection for whistleblowers.

Retaliation is one form of bullying. According to the Workplace Bullying Institute, bullying affects one third of the U.S. workforce.

The institute defines bullying as “repeated, health-harming mistreatment” through verbal abuse, offensive conduct, and work interference.

Current federal and state law protects workers from bullying at the workplace only if they are a member of a “protected status” group, defined by gender, race, religion, ethnicity, and so on, and only if they were bullied by someone who is not a member of such a group.

The institute estimates that 80 percent of workplace bullying is technical legal, for example when a white man bullies a white man, one of the most common forms.

Many speakers at the rally demanded legislation on the state and city level to provide better protection for whistleblowers and other victims of bullying.

An audit at the Laguna Honda hospital has confirmed the misuse of more than $450,000 in donations intended for patients, but which were channeled for staff use, according to the San Francisco Examiner.

With the money returned to the gift fund, the District Attorney’s office never filed a criminal investigation against anyone responsible, including the executive director of Laguna Honda Hospital, who had initiated the misuse, Rivero pointed out.

Kerr sees the situation as systemic in the administration of city departments. “There is a tolerance of incompetence in management, particularly if managers are lackeys,” he said.

“The other problem is dishonesty at every level,” he added. “A dishonest manager here is not seen as a problem by the people on top if they are similarly dishonest.”

Kerr tried to go through the city’s Ethics Commission, but it dismissed his case. Only by suing the city could he prove that was retaliated against for whistleblowing, he said.

More than two years after filing lawsuits, the city settled with Kerr and awarded him $750,000.

According to figures from the city’s Attorney’s office, compiled by the Stop Workplace Bullying Group, more than 100 settlements cost the city $10.3 million between 2007 and 2012 for city employees who filed lawsuits against prohibited personnel actions.