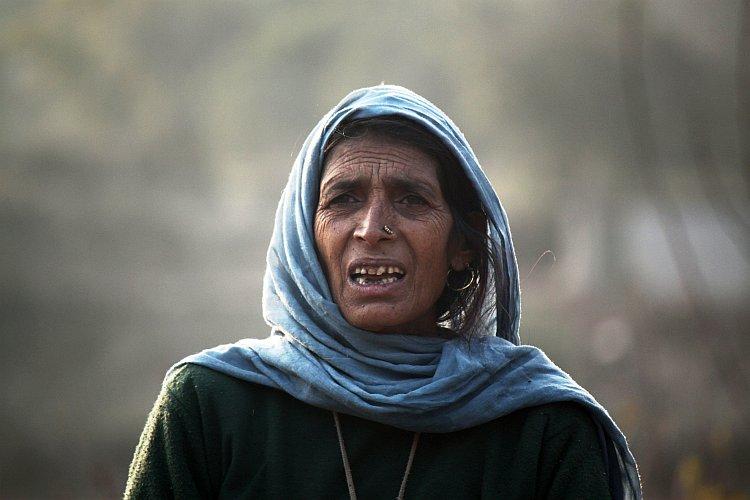

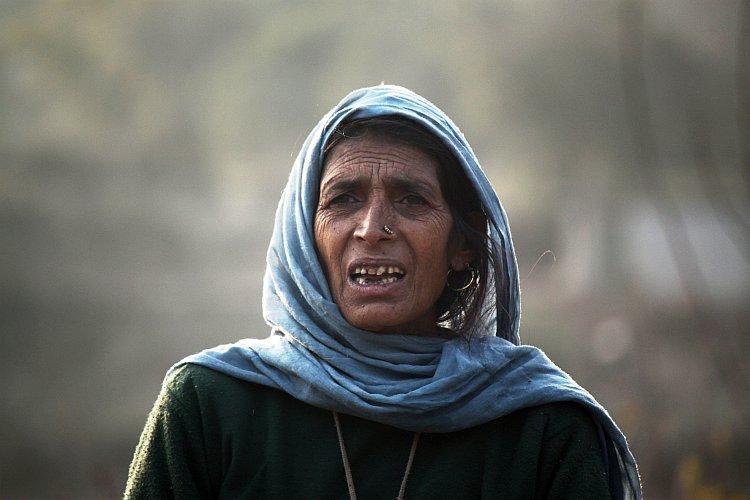

JAMMU, India—Women living in communities in the disputed border region between India and Pakistan have been suffering for decades, though their stories often go unheard amid the clatter of diplomacy and the ongoing militancy in the region.

The conflict between the two neighboring states over the disputed region of Jammu and Kashmir has seen many lives torn apart. Families were divided when the border of Kashmir was drawn in 1947–1949 and redrawn in 1965 and 1971. Although every member of the families became a victim of the division, women have been hit especially hard.

“Women residing on the contested border have endured immensely as a consequence of the six-decade conflict between India and Pakistan,” says Seema Shekhawat, from the University of Mumbai.

Those hardships include being frequently displaced, facing firing and shelling, earning a livelihood from cultivating land with mines, and the general unease of abnormality of life too close to a tense and volatile border, she said.

Amnesty International notes women in the area also face rape and other sexual abuse.

Deep-rooted social gender biases and poverty make life extra hard for women on these disputed borders. Even the region is difficult, being extremely mountainous with few people.

Shekhawat says the voice of women is crucial to understanding the issue.

“They are not only the victims of the division but suffer more acutely due to their very location in a society in which everything, including their rights, are seen through the prism of the patriarchal system,” says Shekhawat.

Many of the communities remain backward with low development, with many only having seen roads and transport appear in the past two decades. Heavy snow in the winters further isolates regions at higher altitudes.

“Farhana,” the factious name of a woman who fears reprisals from her community and militants, knows how difficult that life can be. A Kashmiri, she was born in the difficult Himalayan ranges of Lohai Malhar in the town of Billawar in the Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir. Her difficult life in the dangerous region took a turn for the worse with the death of her husband.

“One day my husband had some pain and there was no hospital nearby where we could take him. He died within twenty-four hours,” Farhana said.

Young widows in this region often end up as servants for the huge joint family clans and mistresses to their dead husband’s brothers. However, with the help of relatives, Farhana, managed to flee to the lower Shivalik ranges, covering the difficult journey mostly on foot with her two sons, and started a new life there away from gender-related vulnerability and fresh cross-border insurgency in the region.

“It had become important to leave my village in Lohia Malhar. The atmosphere had become very dangerous,” Farhana said.

Her troubles however did not end here. One day, her eldest son, then 15, went missing. In the mountains of Jammu and Kashmir, when a young boy disappears, it is most likely he has fallen into illegal border operations. Just last year he miraculously reappeared, nine years after he went missing.

“For nine years every day and night I prayed for his return,” says Farhana.

The nine years were traumatizing for Farhana. Not only had she lost a son, but she was also frequently visited and questioned by police as to his whereabouts. Whenever she was questioned, Farhana remained evasive saying in the local dialect, “O bar chalieera ha” (he had gone out).

“He returned last year and I got him married so that he can settle in life. He has a child now.” She smiles and points at the small shoes lying on the veranda of her new concrete house in the lowlands.

Farhana’s youngest son works six months per year in a cold storage room in Mumbai and the rest of the year he works on the small piece of land his mother purchased selling milk.

Dressed in jeans and sneakers he was going out with his friends to play cricket. “I have two cows and one buffalo. I raised my kids working in the cattle sheds and farms of other people here. I always tell my sons that it’s acceptable to eat only once in a day but it’s bad to eat with money earned the wrong way,” says Farhana.

Farhana doesn’t want her daughter-in-law to meet her same fate, so Farhana is pleased her son’s wife has applied to go to college. “There should be more job avenues for women like us. My daughter-in-law should get educated and should get a job.”

Without the same access to work as men, and because of their fewer rights, women like Farhana have suffered tremendously due to massive security agencies, vulnerable villages, and militants.

When the long-closed traditional routes between the two countries were recently reopened and fresh bus service began, many women came through with stories of the paradoxes and tribulations caused by the often-changing borders.

In one such bus between Poonch in India and Rawalakote in Pakistan was Rabia Bi, alias Satya Devi. She was one of the countless women who were direct victims of the 1947 war between Pakistan and India and subsequent border politics between the two hostile neighbors. Her story has been captured in the book “Women in Indian Borderlands.”

Rabia was just 10 years old when her Hindu family was forced to migrate from Pakistan to India. She got separated from her family’s caravan when it was chased by marauders and was later picked up by an old Muslim woman who married Rabia to her son. She was converted to Islam and given a new identity.

“I’m caught by destiny in its mold. Now I have to spend the rest of my life with him (husband), and with my family there. Who knows better than us or our families that these contours have not been drawn on geographical territories but they so brutally pass through our lives,” Rabia Bi (Satya Devi) said in her book.

Sixty years on Rabia, then a wife, mother and grandmother, visited her surviving siblings, a brother and a sister, and other members of her extended family living in the Poonch District of India.

According to professor Shekhawat, the opening of some of the traditional routes has made it possible for some families—but not all—to be reunited.

“There is a need to open all the traditional routes to facilitate the reunion of divided families. The tragic tales of border women makes the case for humanity to be given due importance rather than stubborn politics of territory and strategic thinking,” she said.

According to Shekhawat the borders must be made a point of contact and become “the sites where not only states meet, but also people.”