During Pope Francis’ recent tour of Mexico, he denounced the country’s illicit drug trade, while calling for social programs to lift up the poor.

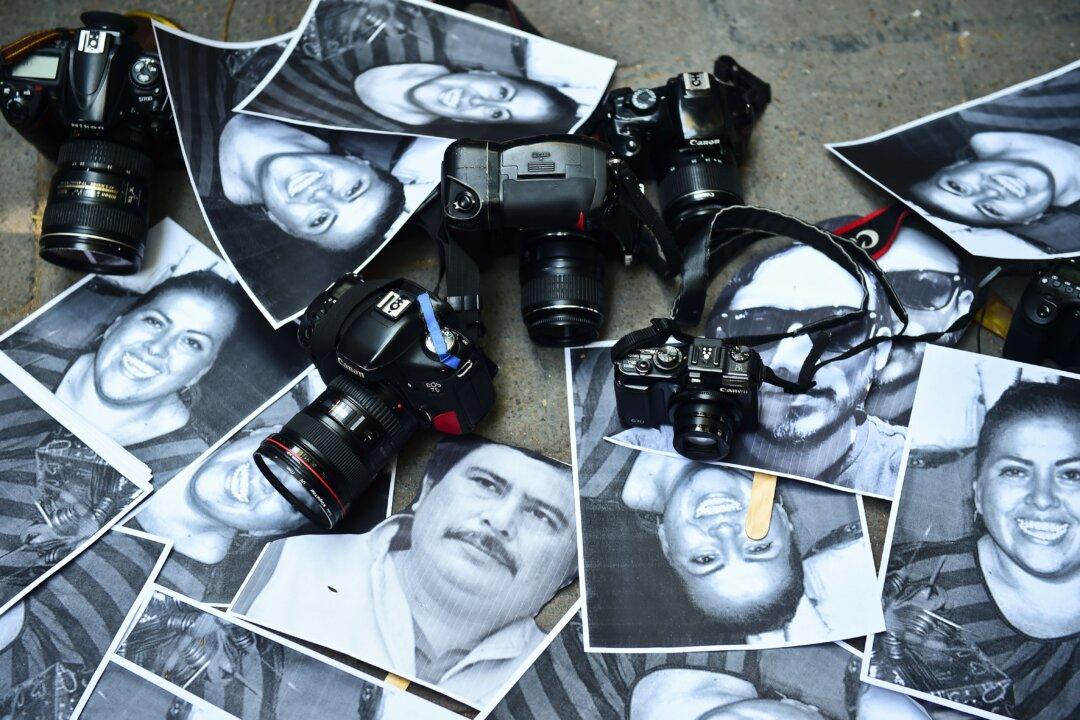

One thing he didn’t explicitly touch on: the precarious situation Mexican journalists find themselves in. In fact, on Feb. 9—four days before the pope’s arrival—the body of El Sol de Orizaba crime reporter Anabel Flores was found on the side of a highway. It was the third murder of a Mexican journalist in 2016.

In the crossfire of drug violence and government corruption, Mexico is one of the world's most dangerous places for journalists.