A fluctuating tilt in a planet’s orbit doesn’t rule out the possibility of life, new research shows. In fact, sometimes it helps.

That’s because such “tilt-a-worlds,” as astronomers sometimes call them—turned from their orbital plane by the influence of companion planets—are less likely than fixed-spin planets to freeze over because heat from their host star is more evenly distributed.

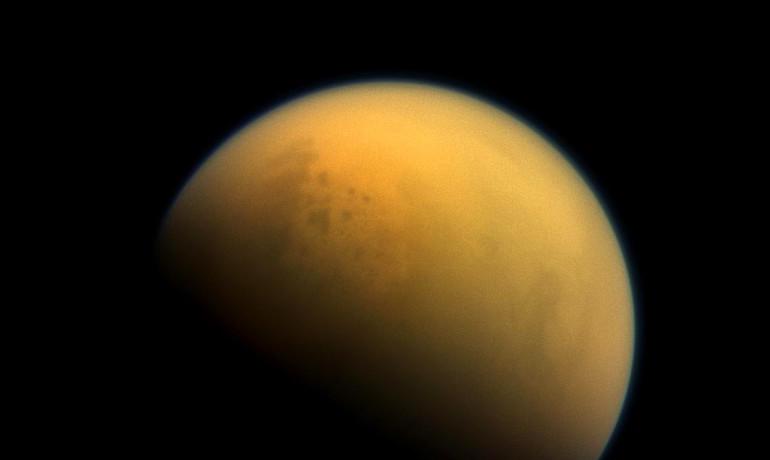

This happens only at the outer edge of a star’s habitable zone, the swath of space around it where rocky worlds could maintain liquid water at their surface, a necessary condition for life. Further out, a “snowball state” of global ice becomes inevitable—and life impossible.

The findings expand the perceived habitable zone by 10 to 20 percent. And that in turn dramatically increases the number of worlds considered potentially right for life.

Such a tilt-a-world becomes potentially habitable because its spin would cause poles to occasionally point toward the host star, causing ice caps to quickly melt.

“Without this sort of ‘home base’ for ice, global glaciation is more difficult,” says Rory Barnes, an astronomer at University of Washington. “So the rapid tilting of an exoplanet actually increases the likelihood that there might be liquid water on a planet’s surface.”

Off-Kilter Planets

Earth and its neighbor planets occupy roughly the same plane in space. But there is evidence of systems whose planets ride along at angles to each other, Barnes says. As such, “they can tug on each other from above or below, changing their poles’ direction compared to the host star.”

For the study, published online in the journal Astrobiology, the team used computer simulations to reproduce such off-kilter planetary alignments, wondering, “what an Earthlike planet might do if it had similar neighbors,” Barnes says.

Their findings also argue against the long-held view among astronomers and astrobiologists that a planet needs the stabilizing influence of a large moon—like Earth has—to have a chance at hosting life.

“We’re finding that planets don’t have to have a stable tilt to be habitable,” Barnes says. Minus the moon, Earth’s tilt, now at a fairly stable 23.5 degrees, might increase by 10 degrees or so. Climates might fluctuate, but life would still be possible.

‘A Lot of Real Estate’

“This study suggests the presence of a large moon might inhibit life, at least at the edge of the habitable zone.”

Expanding the habitable zone might almost double the number of potentially habitable planets in the galaxy, says first author John Armstrong.

Applying the research and its expanded habitable zone to our own celestial neighborhood for context, “would give the ability to put Earth, say, past the orbit of Mars and still be habitable at least some of the time—and that’s a lot of real estate.”

Victoria Meadows, Thomas Quinn and Jonathan Breiner of the University of Washington and Shawn Domagal-Goldman of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center are coauthors of the study. The NASA Astrobiology Institute provided funding.

Source: University of Washington. Republished from Futurity.org under Creative Commons License 3.0.