Was May 2016 the month that faith in print newspapers finally died?

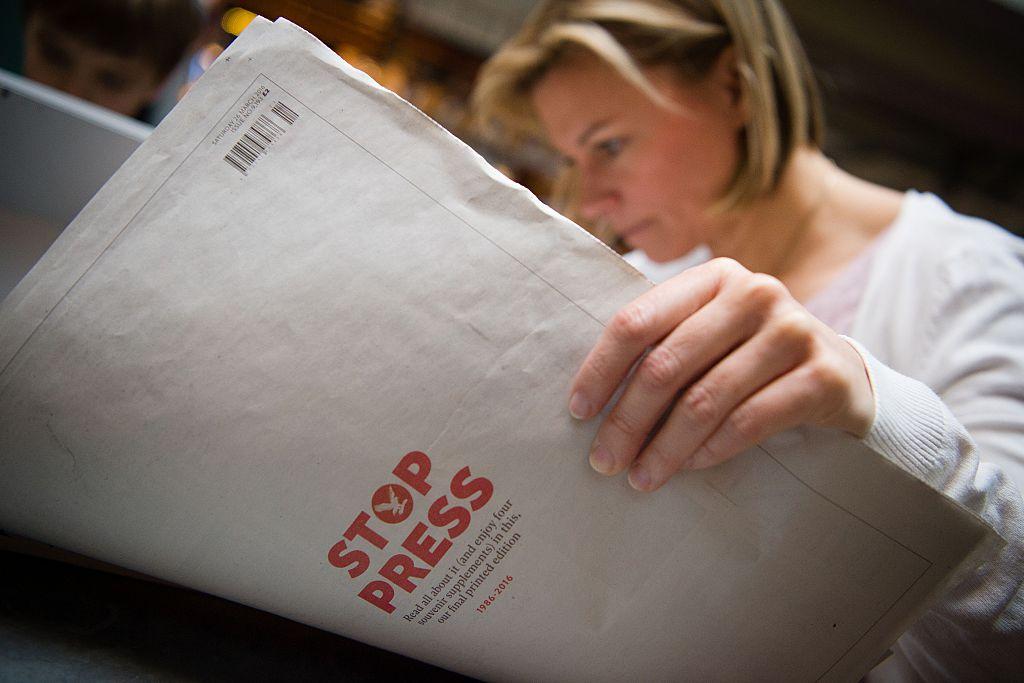

On May 6, The New Day, a tabloid print-only newspaper launched by publisher Trinity Mirror in the U.K., shut down. The paper was the first new national daily newspaper in the U.K. for 30 years. It closed after just nine weeks.

The New Day seemed like a last-ditch attempt to sail a boat of print against the tidal wave of online news.

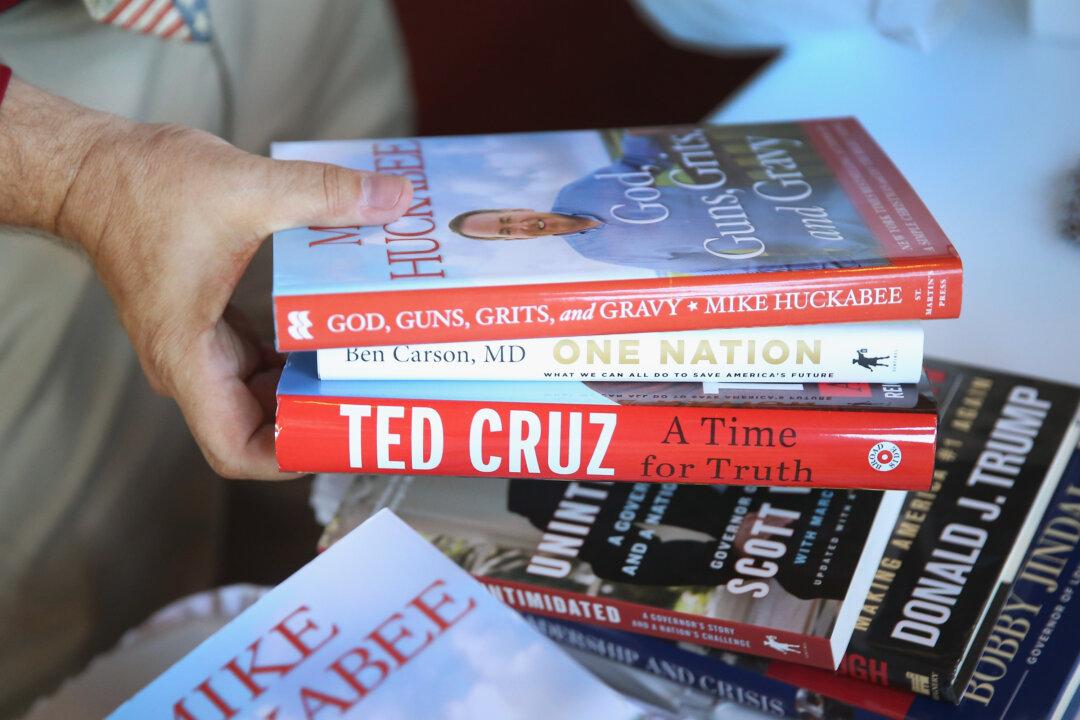

This is just one episode in the dramatic upheaval taking place in the world of journalism that also has seen the shutting down of once established newspapers as well as the emergence of the “citizen journalist” and the popularity of instant, real-time, unmediated news on digital and social media.

Much of this information is self-promoting, unedited and not fact-checked. The current freewheeling world of news seems like journalistic hell to many in a business where American newsrooms shrank by 40 percent between 2007 and 2015.

But as our research shows, the decline of print journalism will not be the end of news. Not only does this reassure the two of us about the “crisis in journalism." Our many years of studying the story of news from the 17th century on make us positive about the future. Change, not stability, has been the steady state of news over the long arc of history.

News Isn’t the Same as Journalism

The root of the present pessimism lies, we believe, in the failure of reporters, editors and scholars to draw a distinction between journalism and news.

Reams have been written, for example, about how journalism needs a 21st-century creed or must adopt values of transparency instead of objectivity.

Journalism is a type of news reporting that has existed for a relatively brief period.

Professional journalism is younger than professional baseball and psychoanalysis. While the term journalism emerged in the early 19th century, it established professional codes, education, and associations only in the early 20th century. The first school of journalism in the United States, for example, was established at the University of Missouri in 1908.

News, on the other hand, has been with us for centuries.

News existed before the concepts of fairness and objectivity, before anyone thought a newspaper should have editors and reporters.