WASHINGTON—How do you know when you are obsessed with something? The dictionary definition states you have an idea or thought that is constantly on your mind.

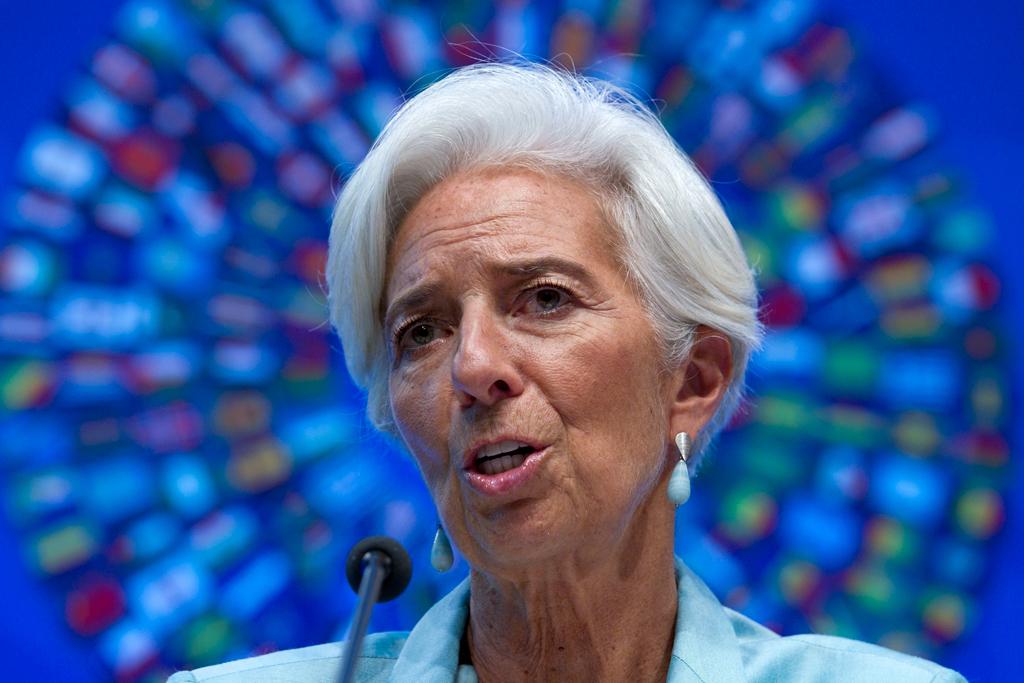

At its annual meetings last week, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) showed it is absolutely obsessed with economic growth. During the presentation of the World Economic Outlook and its prediction for global growth, the word “growth” occurred 37 times, more than any other. Add another 22 occurrences during the press conference of Managing Director Christine Lagarde and 16 during a conference regarding financial stability, and you can safely say the institution is obsessed with growth.

“My hope at the end of the annual meetings is that each finance minister, each governor of the central bank, will go back home thinking what can I do in order to propel that growth, which is currently too low for too long, benefiting too few,” Lagarde said at a conference on Oct. 6.

Growth Isn’t Necessary

Economic growth is good in principle. Companies invest and generate a return on the capital invested through increased economic output and productivity. More jobs, more goods, more of everything.

However, it is worthwhile to note that an economy doesn’t need to grow under all circumstances and at any price, especially not when narrowly defined as growth in GDP, a flawed statistical concept. This is mostly true for developed economies: Like a tree that has reached its full height, the economy doesn’t need to grow to provide for all of its citizens.

The oldest tree in the world is located in Sweden and is called Old Tjikko. Scientists say it’s 9,550 years old. It stopped growing a long time ago and is in great shape. It just settled into a natural rhythm without the ambition to grow into the sky.

This principle is working in places like Japan with a shrinking population, where total GDP has hardly budged over the last 10 years, but GDP per capita went up because of increases in productivity. There is the problem of distribution of income, but that’s a different problem and also present when the economy is growing at 10 percent, like in China over the past decade.