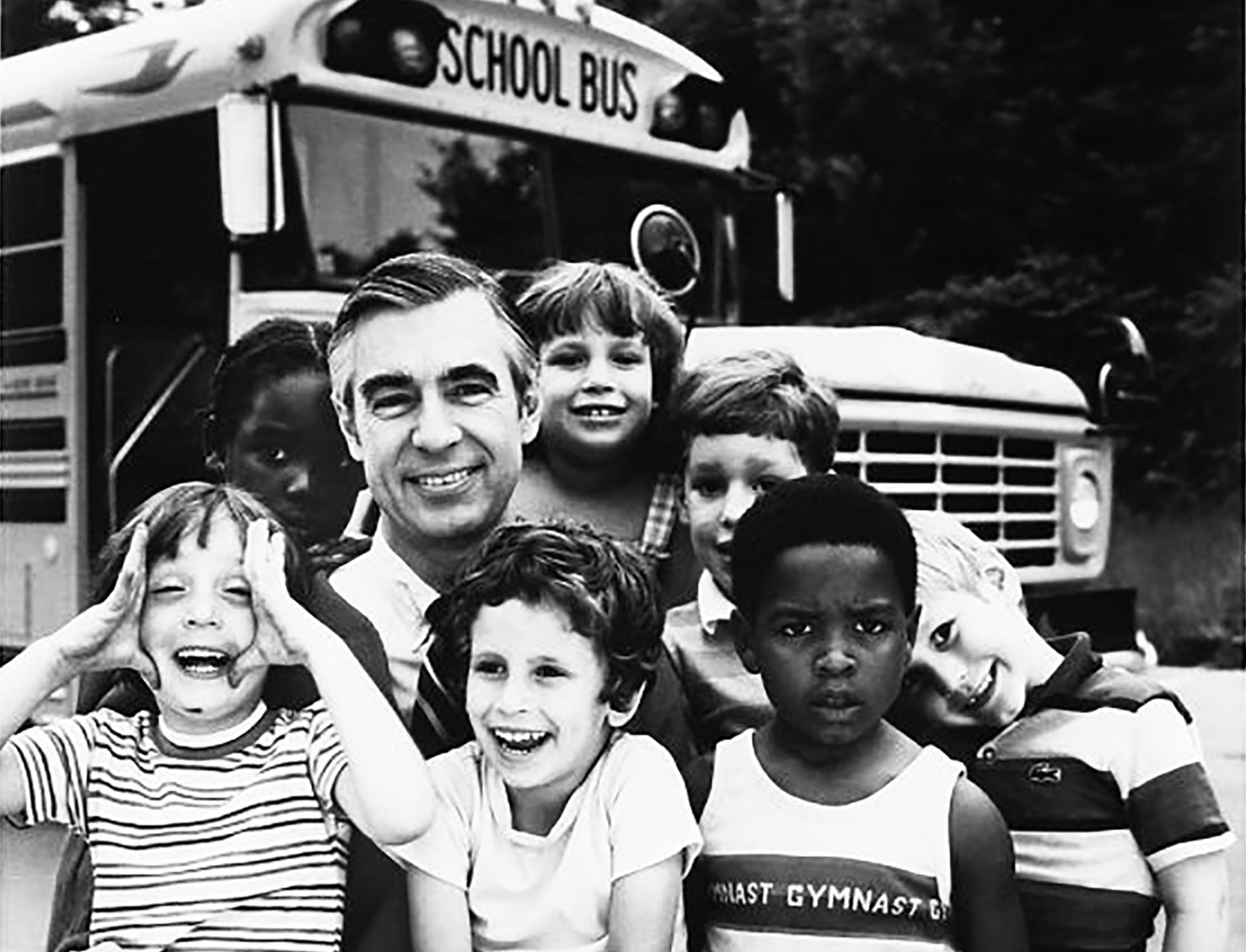

From 1968 to 2001, tens of millions of Americans, most of them children, watched “Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood” on television. He enthralled the preschool set, puzzled many adults—was this guy for real?—and was so one-of-kind that comedians such as Eddie Murphy parodied him.

Behind his famous pair of sneakers and cardigan sweater, Fred Rogers (1928–2003) was a man of many talents and gifts. He was a musician and songwriter, composing most of the songs used on his show. Although he never headed up a church, he was an ordained Presbyterian minister and a lifelong reader of the Bible. He studied child psychology and was a pioneer in children’s television.