PONTE VEDRA BEACH, Fla.—A band of researchers barely notice as the sun peeps over the Atlantic Ocean, sending orange streaks shooting across jagged gray clouds.

It’s treasure they’re seeking.

So as they set out across wave-smoothed sand, they’re focused only on spotting clues that will lead them to their prize.

Every morning from April 15 until Oct. 31, so-called turtle patrols embark on a similar quest across Florida coastlines.

In cooperation with the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC), they document, monitor, study, and try to protect the nests of five species of sea turtles that venture onto the state’s beaches.

All are officially listed as threatened or endangered. There are seven sea turtle species worldwide.

When the time is right for nesting, a female turtle crawls from the waves at night and lays her eggs—usually about 115 at a time—in a hole she digs in Florida’s sugary beach sand.

But Florida’s beaches don’t make the gentlest nurseries for baby turtles.

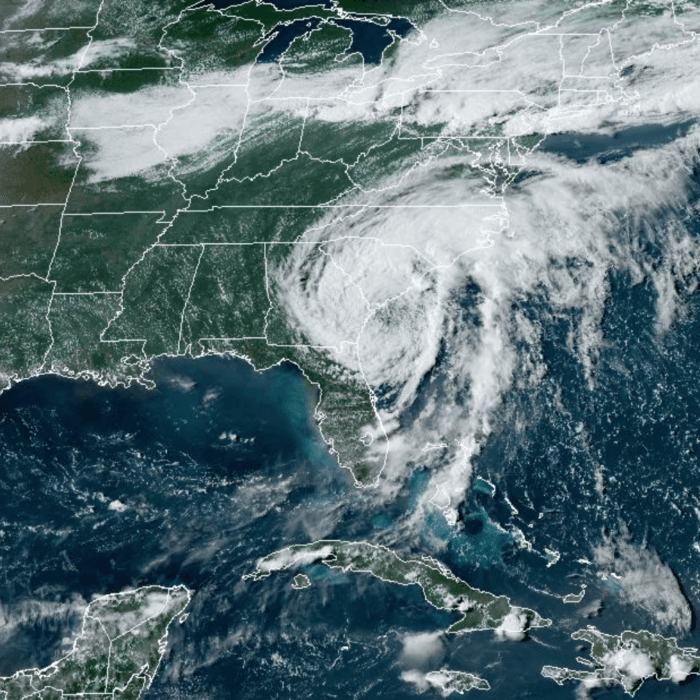

Severe storms periodically lash dunes concealing turtle nests, as Hurricane Debby did on Aug. 5.

Debby was the fourth named storm of the 2024 Atlantic hurricane season, which began on June 1 and runs through Nov. 30.

In May, forecasters with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration predicted that this year would bring “above-normal hurricane activity in the Atlantic.”

They blamed “near-record warm ocean temperatures,” along with “La Nina conditions in the Pacific, reduced Atlantic trade winds and less wind shear.”

The 2023 hurricane season brought strong weather to Florida, too. It ranked fourth for most named storms since 1950. There were 20.

Seven evolved into hurricanes; three intensified into major hurricanes.

Only Hurricane Idalia made landfall, thrashing Keaton Beach, Florida, as a Category 3 storm and causing storm surges of seven to 12 feet of water in low-lying areas.

The weakest hurricanes, with winds of 74 to 95 miles per hour, are Category 1 storms. The most violent are the Category 5 systems, leaving swaths of destruction caused by winds greater than 155 miles per hour.

But despite the harsh weather spiraling around and across Florida, sea turtles—protected by both Florida and federal law—seem to be thriving.

Last year was a record year for sea turtle nests in Florida.

“Every year we do lose some sea turtle nests to hurricanes,” said Lucas Meers, coordinator for the Mickler’s Landing Turtle Patrol.

“I am a little bit concerned with the higher intensity of hurricanes [predicted] earlier in the season.”

But mother sea turtles seem to know the risks instinctively, according to Justin Perrault, vice president of research at Loggerhead Marinelife Center.

So they don’t put all their eggs in one basket, so to speak.

“Sea turtles can nest multiple times in one year,” Meers said.

High Stakes Forensics

On this day, a few minutes into their daily hike, volunteers on patrol with Meers spot the prize they sought.A set of tracks stretches from the surf to a dune and back to the water.

To the uninformed beach walker, the pattern suggests that a small child perched behind a teeny steering wheel may have driven a battery-operated car across the sand in a large, wavering loop.

But turtle enthusiasts immediately know what happened here.

A female sea turtle lumbered out of the water, possibly crawling onto land for the first time in years. Males don’t leave the surf.

With plodding determination, she churned the beach sand with alternating flippers, slowly dragging her 300-pound body to the spot deemed best for a nest.

Instantly, Meers identified the species of turtle that was here. Loggerhead.

Meers instructed his team, “Take photos of everything before touching anything.”

Unlike loggerheads, green turtles move both flippers in unison, leaving a distinctly different pattern in the sand.

A leatherback leaves tracks so far apart that Meers—who’s 6 feet, 3 inches tall—can lie between them, with his feet within one flipper’s marks and his head within the other flipper’s perforations in the sand.

Today’s tracks end at a barely visible depression along a low dune, then loop back to the ocean.

‘Hot Chicks and Cool Dudes’

It’s clear that the mother turtle crawled back to the waves after her hours-long task. She won’t return to check on or care for the clutch of about 115 eggs.

Although lacking in maternal instinct, sea turtles are prolific. They may build six to eight nests in one nesting season. They nest one season every two to three years.

Ping pong ball-sized eggs are left in a three-foot-deep hole in a pile the turtle covers completely.

The eggs are incubated by the warm sand, usually emerging in about 55 days.

In especially hot and dry weather, hatching could occur 10 days earlier. Or the youngsters could emerge after 55 days if it has been rainy.

When nests get particularly warm, mostly female hatchlings will emerge. When there are cooler temperatures, the sex of the hatchlings will be mostly male.

“Think hot chicks and cool dudes,” Meers said, grinning.

And if a hurricane lashes the beach and rising water covers the nest, the “washover” won’t necessarily harm the developing turtles, he said.

So far this year, there are fewer nests.

But there have been more “false crawls,” a term for when a female comes onto the beach, then retreats back into the surf without laying eggs.

Those turtles may be finding that the beaches are too hard-packed after “renourishment” projects, during which millions of dollars are spent on building back eroded dunes, Meers said.

Female turtles seem to prefer beaches with softer sand, where it’s easier to dig, he said.

But researchers aren’t worried by the downturn this season.

“You’re looking at turtle species that take a long, a long time to reach sexual maturity, so you need to look at generational trends,” Meers said.

“Over decades is what you’re looking for with these population trends. Just because we had a record year last year, and we have an average year this year, that doesn’t mean the numbers are crashing.

Man on a Mission

For 14 years, Meers has combed beaches at daybreak for evidence of sea turtle activity. For the past four, he’s been a paid researcher holding a permit with FWC to collect data on turtles.He now organizes a team of dozens of volunteers to scour a 4.6-mile stretch of remote beach behind upscale homes that stay vacant much of the year.

Growing up shy, Meers wouldn’t have dreamed of managing a team of people devoted to helping turtles.

But at Jacksonville University, while studying biology and marine science, he discovered his passion.

He said, chuckling, “I came out of my shell.”

Disturbing sea turtles and their nests is a crime punishable by a fine of up to $100,000 and a year in prison.

But turtle patrollers have special governmental permission.

Under strict rules, they document details and mark each nest in an effort to keep them from being disturbed by humans or lost in a storm.

When his team finds a new nest, they dig down about a foot to remove one freshly laid egg. It’s passed along to scientists studying the genetics of nesting turtles.

With it, they’ll be able to tell which other nests have been created by the same mother turtle.

They’re not sure yet whether mother turtles return to the beach where they hatched to lay their eggs. But it does seem that they return to the same beaches year after year.

The egg studies have revealed that younger turtles may spread their nests across 500 miles of beaches. Older turtles seem to prefer a stretch of beach about one to two miles long.

At a newly discovered nest, volunteers placed wooden stakes around the nest and created a barrier with tape. They also posted a sign warning of penalties for disturbing the nest.

Most of the time, the team’s efforts to delineate nests keep away miscreants, Meers said. But not always.

If they don’t mark the nests on the morning after they’re created, there will be no way to detect them and protect them, he said.

Within hours, the new nests will be smooth, flat, and undetectable. Mother turtles seem to want it that way.

So the team takes pictures and measurements of other stakes they tap into the sand farther back on the dunes.

If a hurricane strikes and markers surrounding the nest are washed away, measurements and photos could help them find the nest again.

“When hurricanes come in and bring in the low pressure and the tide, especially if it’s paired with the high tide, we‘ll get captive waves that wash out the nest completely and it’ll totally decimate the beach, totally take out all the nests,” Meers said.

All they can do is hope that doesn’t happen.

With the new nest documented, the team hikes on. Now they’re seeking a nest that showed signs that hatchlings had emerged a few days earlier.

Today, they’ll do what’s known as an “evaluation.”

Researchers don’t approach nests for several days after the emergence of young. That’s in case more hatchlings are still making their way out in what seems to be a cooperative process.

At night, hatchlings work together to push through the heavy wet sand, Meers said. They stop their frenzied movement when it starts to get hot during the day. They start again at nightfall when it cools.

Interaction with hatchlings, even by researchers, is discouraged out of concern that it will disrupt the turtles’ behavior and development in ways not yet understood.

At the evaluation site, all that remains are four stakes encircled by a strand of orange tape and a slight depression in the sand.

Emanating from the depression are little, parallel tracks made by tiny flippers, with a smooth line in the middle made by the tiny turtle’s plastron.

The Best Nest

Volunteer Abby Kuhn drops to the sand and begins to dig, eventually pulling out one fragmented egg after another. Meers sorts them.They know there were 113 eggs in this nest because it was relocated. They aim to account for all of the eggs to determine how many babies emerged.

The mother turtle originally laid these eggs on a stretch of beach farther north that’s undergoing dune renourishment.

Bulldozers needed to push the powdery sand back up into gentle hills that can serve as crucial barriers between the surf and seaside buildings. Workers needed to replace washed-away native plants, helpful in holding dunes in place.

A turtle nest built there would have been crushed in the process.

So the turtle patrol team moved it.

Shell Shocked

Then, at a site deemed safer, they do their best to replicate the depth and the upside-down lightbulb shape of the original hole dug by the turtle.Then they place each egg in the new nest mimicking its original orientation.

Because the embryos have begun to develop, putting them back in a new position could keep the hatchlings from climbing out, Meers says.

Suddenly, there’s a surprise. A true treasure.

Gently, Kuhn lifts out a loggerhead hatchling smaller than the palm of her hand. Then there’s another found trapped at the bottom of the hole. Then another.

It’s unusual, but this was a nest built by humans, not a mother turtle, Meers says, shrugging.

Humans don’t know all the secrets to successful nest construction.

A few minutes later, the tiny turtles are pointed in the direction of the surf and released. Instinct kicks in, and they flap their front flippers frenetically, dragging themselves slowly but steadily toward the lapping waves.

Gulls, excited about a potential meal, scream overhead, darting and swooping.

But the researchers don’t intervene.

Scientists believe that the process of crawling to the water’s edge may help baby turtles properly imprint on the beach where they hatched. The effort also may build their strength for the journey that lies ahead, Meers said.

As the hatchlings set out, morning beach walkers gather, keeping their distance, to watch the rare daytime spectacle.

All at once, they gasp, then groan with disappointment as a gull scoops up a baby turtle a few feet from the lapping surf.

Moments later, they cheer together when the hatchling drops from the bird’s beak unharmed. Splashing down into the water, it swims away.

Within a few minutes, all the hatchlings have reached their first destination. Lapping waves push them back, then pull them out, until they all disappear.

They still face a perilous journey.

Now, they’ll have to swim about 50–100 miles to reach the Sargasso Sea, where they’ll grow from the relative safety of floating islands of sargassum seaweed.

In 17 to 35 years, the surviving females will crawl back onto land for the first time, finally mature enough to make their own nests.

Will they be drawn to the place where they were hatched?

Turtles in Florida

Making up about 95 percent of the nests on Florida beaches are the slow-swimming loggerheads. Adults often weigh 275 pounds or more and sport shells about three feet long.More rarely, turtle patrols find nests of other species, including green turtles, about the same size as loggerheads. They were prized by early European settlers for their meat, eggs, and fat, used to make a tasty turtle soup.

Smaller hawksbill turtles attract poachers who turn their shells into jewelry and hair decorations.

Leatherbacks—up to 10 feet long and weighing up to a ton—can travel thousands of miles from their preferred beaches in Florida. The behemoths can dive 3,000 feet below the ocean’s surface searching for meals of jellyfish.

Finding nests of the rarest turtles always sparks excitement among turtle patrol teams.

But sometimes they make other discoveries even more unexpected.

Meers’s team once found a kilo of cocaine and turned it over to law enforcement. Another team found 70 pounds of the drug and 40 pounds of marijuana.

How Beach Visitors Can Help Turtles

Sea turtle nests are found more rarely on beaches as far north as North Carolina, Meers said. And one nest was reported even farther north, in Maryland.For visitors to Florida beaches, Meers offers this advice: “What you can do to help protect turtles is keep the beach clean, dark, and flat.”

Trash left behind, even just tiny pieces, can be mistaken by turtles as food and can lead to choking or entanglement.

Lights left on near beaches can cause hatchlings, which usually emerge at night, to go in the wrong direction and fail to make it to the water, he said.

And beachgoers should fill all the holes they’ve dug in the sand and knock down sand castles when they leave. Both can block or trap baby turtles on their race to the water.

“They already have to contend with a ton of predators,” Meers said. “And then once they get into the water, they have to [avoid] sharks, fish. They’re little protein packs for the entire food chain.

“But we want to reduce their challenges as much as possible.”

In June, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis signed into law a measure meant to help turtles and other sea life by banning the intentional release of balloons.

When balloons pop and drift down, the remnants can be mistaken for food by sea turtles and other creatures. Even cows have died from ingesting balloons. Balloon strings can be deadly, too, causing entanglement, drowning, and strangulation.

Already, volunteers are picking up fewer balloons on their daily patrols that happen rain or shine, Meers said.

And Floridians seem to have caught the vision and have developed “a culture of respect” for marine life.

“People generally don’t mess with sea turtle nests,” Meers said. “When they see a sea turtle nest on the beach, they respect it, for the most part.”

Florida organizations and governments have preached about the importance of wildlife conservation for decades, he said. And it’s catching on.

But turtles bring something else to the equation, according to Meers. He calls it the “cuteness factor.”

“People just love what little baby sea turtles look like,” he said. “I mean, how could you not love a baby sea turtle?”

They are, after all, a Florida treasure.