Almost a century before Columbus sailed the ocean blue to America, Chinese admiral Zheng began the first of seven expeditions to explore the southern seas. Together with his 30,000 sailors and 300-ship fleet, Zheng’s travels took him through the Malay and Indonesian islands, along the Indian and Arabian coasts, all the way down to the Cape of Good Hope—the southern tip of Africa.

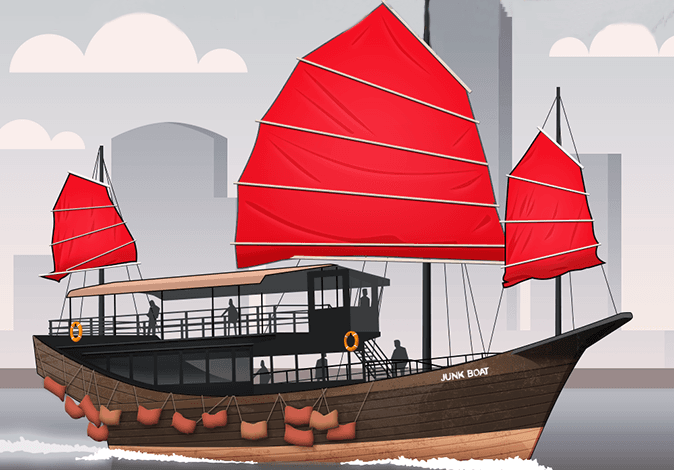

Courtesy of HotelClub