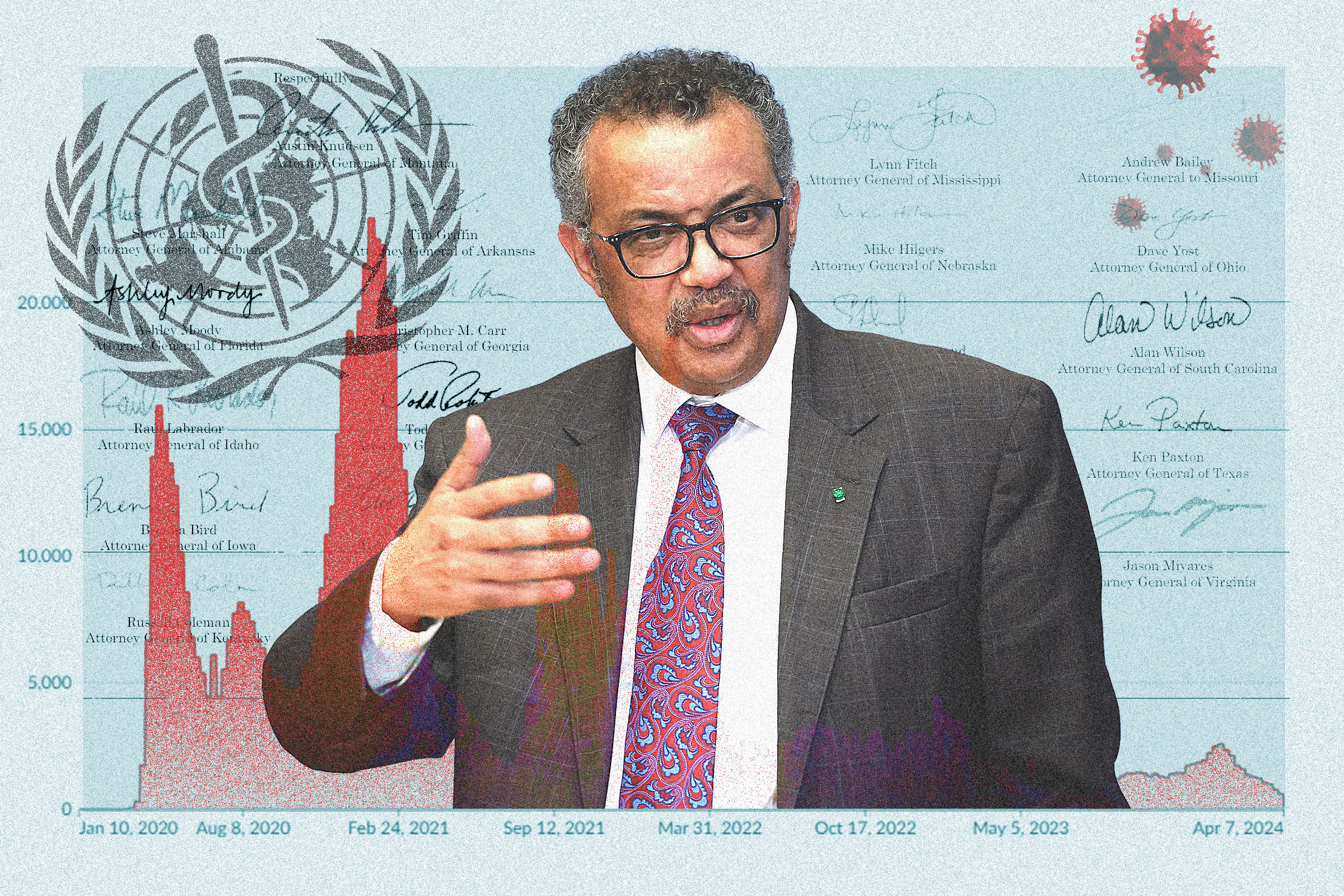

The World Health Organization (WHO) has watered down some provisions of its pandemic agreements ahead of the upcoming World Health Assembly on May 27. Critics in the United States, however, say the changes don’t do enough to address the concerns over the policy.

Provisions in prior drafts of the WHO pandemic treaty and International Health Regulations (IHR) together aimed to effectively centralize and increase the power of the WHO if it declares a “health emergency.”