Whistleblowers should be hailed as heroes but are all too often stigmatized, harassed, marginalized and blacklisted for life, says the former public servant who blew the whistle on the federal sponsorship scandal.

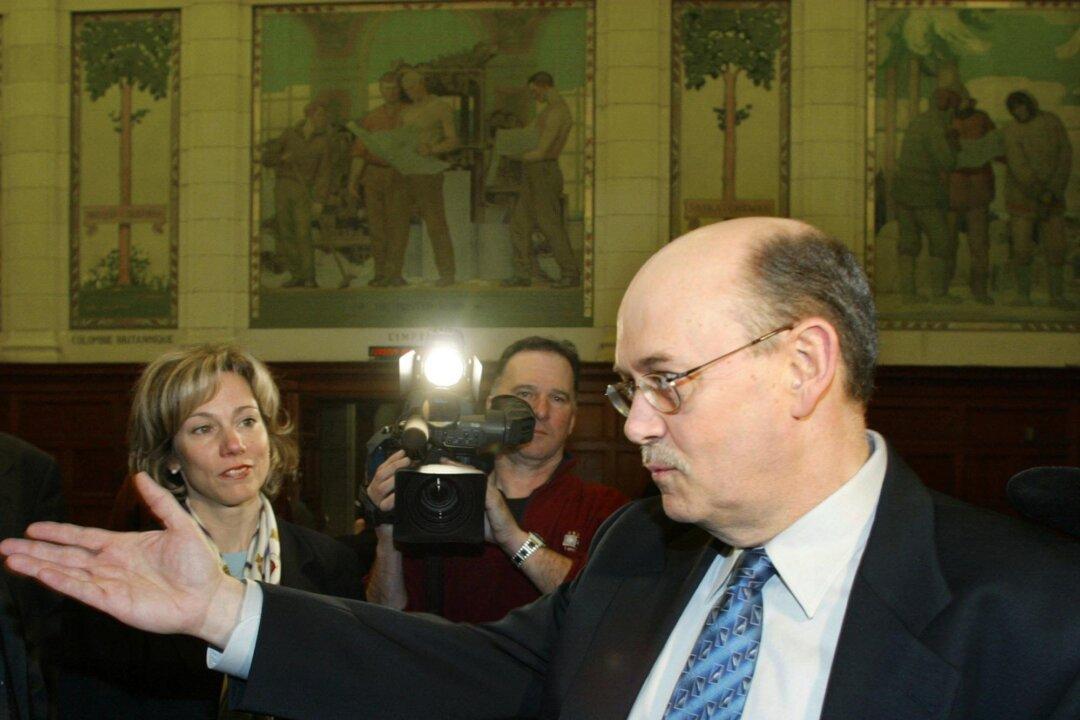

In 2004, former Public Works bureaucrat Allan Cutler triggered one of the biggest political scandals in modern Canadian history when he revealed that millions in public funds were being misdirected to Liberal-friendly advertising firms—a scandal that contributed to the Liberal party’s defeat two years later in the federal election.

Cutler was vilified, monitored, threatened, and demoted, before being finally vindicated by a 2006 inquiry into the scandal.

But Cutler’s battle has never really stopped. The stress of the ordeal damaged his health and forced him into early retirement. His reputation as a whistleblower consistently blocks him from professional and personal opportunities, he says.

“My life is totally different because of what I went through,” says Cutler, adding that many whistleblowers share a similarly traumatic experience.

“The consequences for whistleblowers range from being dead-ended in a job to being fired, to your health permanently destroyed, your self-confidence ruined, nervous breakdowns, suicide. It’s a whole range of things.”

A committed anti-corruption champion, Cutler formed the non-profit group Canadians for Accountability (C4A) in 2008 to actively assist whistleblowers, improve legislation, and raise awareness.

He says there have been at least two instances where former whistleblowers have asked to have their information removed from the C4A website because the connection was hurting their career opportunities.

“The whistleblower, who did the right thing, is regarded with suspicion. Instead of being lauded for exposing corruption, he now needs to cover up his involvement due to the stigma of being a whistleblower,” he wrote in a recent op-ed.

Cutler estimates about 70 percent of whistleblowers who come to C4A for help are public servants. In his experience it’s the culture of the organization, both in the public and private sectors, that most often keeps employees from blowing the whistle—and ostracizes the ones who do step forward.

“They all believe in whistleblowing, in doing the right thing, until it affects them,” he says. “It’s [seen as] an evil thing to break the culture of an organization.”

Protection Lacking

It’s no secret that whistleblowers around the world face bullying. A recent study by the U.S.-based Ethics Resource Center found an 85 percent increase in retaliation against whistleblowers between 2007 and 2012.

But Canada lags behind other developed countries in whistleblower protection due to severely weak or non-existent legislation, Cutler notes.

The latest legislation, the 2007 Public Servants Disclosure Protection Act (PSDPA), introduced in the wake of the sponsorship scandal, has been widely criticized for being narrow in scope, unrealistic, and fundamentally weak. The Federal Accountability Initiative for Reform, a charity that supports whistleblowers, lists more than two dozen significant shortcomings in the act on its website.

In addition, the agency created to administer the PSDPA, the Office of the Public Sector Integrity Commissioner (OPSIC), has itself been plagued by controversy. To date, OPSIC has found only eight instances of wrongdoing in over 600 potential cases.

A comprehensive national whistleblower protection law is desperately needed in Canada, says Cutler, both for the private and public sectors. But equally important is to change the culture and stigma around whistleblowing. Instead of being regarded as snitches, tattletales, or traitors, organizations need to view whistleblowers as an asset.

Cutler likens the stigma to that of women’s rights, smoking laws, or drunk driving—it can take decades to shift cultural perceptions.

“The sensitivity is there, the awareness is there, but the acceptance of the whistleblower is not there, and that could take another 20 years,” he says, adding that awareness increased significantly after the sponsorship scandal.

Whistleblower Award

On March 31, C4A will hold its seventh annual Golden Whistle Award, which recognizes an individual who has done a service to Canada “in the pursuit of truth and accountability.”

This year’s recipient is Sylvie Therrien, a former Employment Insurance investigator for the federal government. Therrien exposed so-called “fraud quotas” last year when she leaked documents showing that the government instructed EI investigators to crack down on about $485,000 in EI fraud each year, part of a plan to save money by cutting benefits.

She says she was penalized for not meeting her monthly quota, and was encouraged by managers to bend the rules to find savings.

Last year’s award winner was Evan Vokes, a professional materials engineer at TransCanada Pipelines. He was fired by the company after raising concerns that the failure to follow code and regulation was key in the catastrophic failure of a pipeline.

Other past winners include Perry Dunlop, who exposed the sexual abuse of minors in Cornwall, Ontario, and Sean Bruyea, a Gulf War veteran who was harassed by Veteran’s Affairs officials after he became a vocal critic of the New Veterans Charter.