LDN 483 [1] is located about 700 light-years away in the constellation of Serpens (The Serpent). The cloud contains enough dusty material to completely block the visible light from background stars. Particularly dense molecular clouds, like LDN 483, qualify as dark nebulae because of this obscuring property. The starless nature of LDN 483 and its ilk would suggest that they are sites where stars cannot take root and grow. But in fact the opposite is true: dark nebulae offer the most fertile environments for eventual star formation.

Astronomers studying star formation in LDN 483 have discovered some of the youngest observable kinds of baby stars buried in LDN 483’s shrouded interior. These gestating stars can be thought of as still being in the womb, having not yet been born as complete, albeit immature, stars.

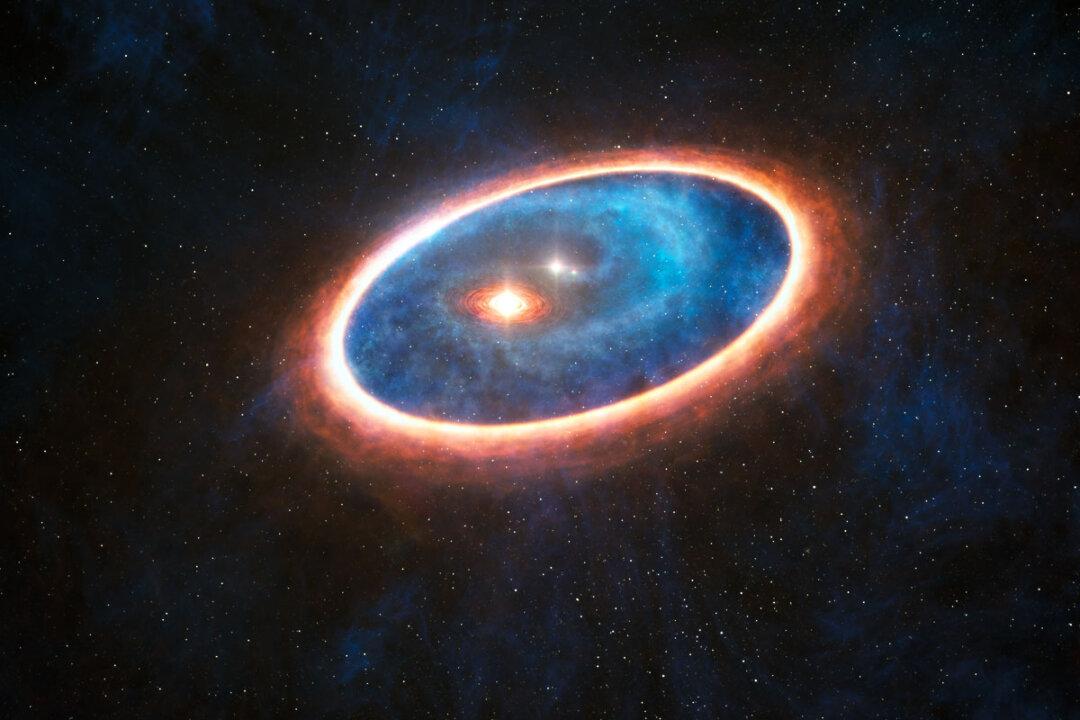

In this first stage of stellar development, the star-to-be is just a ball of gas and dust contracting under the force of gravity within the surrounding molecular cloud. The protostar is still quite cool — about –250 degrees Celsius — and shines only in long-wavelength submillimetre light [2]. Yet temperature and pressure are beginning to increase in the fledgling star’s core.

This earliest period of star growth lasts a mere thousands of years, an astonishingly short amount of time in astronomical terms, given that stars typically live for millions or billions of years. In the following stages, over the course of several million years, the protostar will grow warmer and denser. Its emission will increase in energy along the way, graduating from mainly cold, far-infrared light to near-infrared and finally to visible light. The once-dim protostar will have then become a fully luminous star.

As more and more stars emerge from the inky depths of LDN 483, the dark nebula will disperse further and lose its opacity. The missing background stars that are currently hidden will then come into view — but only after the passage of millions of years, and they will be outshone by the bright young-born stars in the cloud [3].

Notes

[1] The Lynds Dark Nebula catalogue was compiled by the American astronomer Beverly Turner Lynds, and published in 1962. These dark nebulae were found from visual inspection of the Palomar Sky Survey photographic plates.

[2] The Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), operated in part by ESO, observes in submillimetre and millimetre light and is ideal for the study of such very young stars in molecular clouds.

[3] Such a young open star cluster can be seen here, and a more mature one here.