With spring training underway and the 2014 baseball season looming, names and nicknames and terms from the national pastime’s history are cropping up. How did this language originate? Not many would pass a quickee quiz on the topic. But for those of you who wonder about the grade you would get—here are the answers.

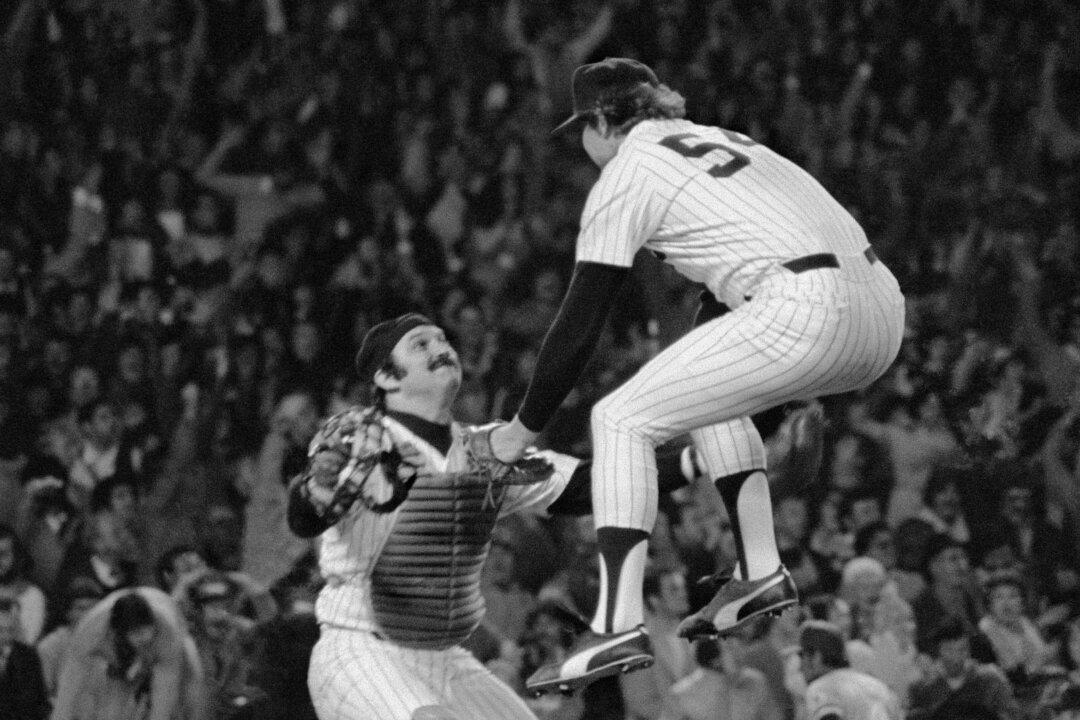

AMAZIN‘ METS: The first run they ever scored came in on a balk. They lost the first nine games they ever played. They finished last their first four seasons. Once they were losing a game, 12-1, and there were two outs in the bottom of the ninth inning. A fan held up a sign that said “PRAY!” There was a walk, and ever hopeful, thousands of voices chanted, “Let’s go Mets.” They were 100-l underdogs to win the pennant in 1969 and incredibly came on to finish the year as World Champions. They picked the name of the best pitcher in their history (Tom Seaver) out of a hat on April Fools’ Day. They were supposed to be the replacement for the Brooklyn Dodgers and the New York Giants. They could have been the New York Continentals or Burros or Skyliners or Skyscrapers or Bees or Rebels or NYB’s or Avengers or even Jets (all runner-up names in a contest to tab the National League New York team that began playing ball in 1962). They’ve never been anything to their fans but amazing-the Amazin’ New York Mets.

BAT DAY: In 1951 Bill Veeck (“as in wreck”) owned the St. Louis Browns, a team that was not the greatest gate attraction in the world. (It’s rumored that one day a fan called up Veeck and asked, “What time does the game start?” Veeck’s alleged reply was, “ What time can you get here?”) Veeck was offered six thousand bats at a nominal fee by a company that was going bankrupt. He took the bats and announced that a free bat would be given to each youngster attending a game accompanied by an adult. That was the beginning of Bat Day. Veeck followed this promotion with Ball Day and Jacket Day and other giveaways. Bat Day, Ball Day, and Jacket Day have all become virtually standard major league baseball promotions.

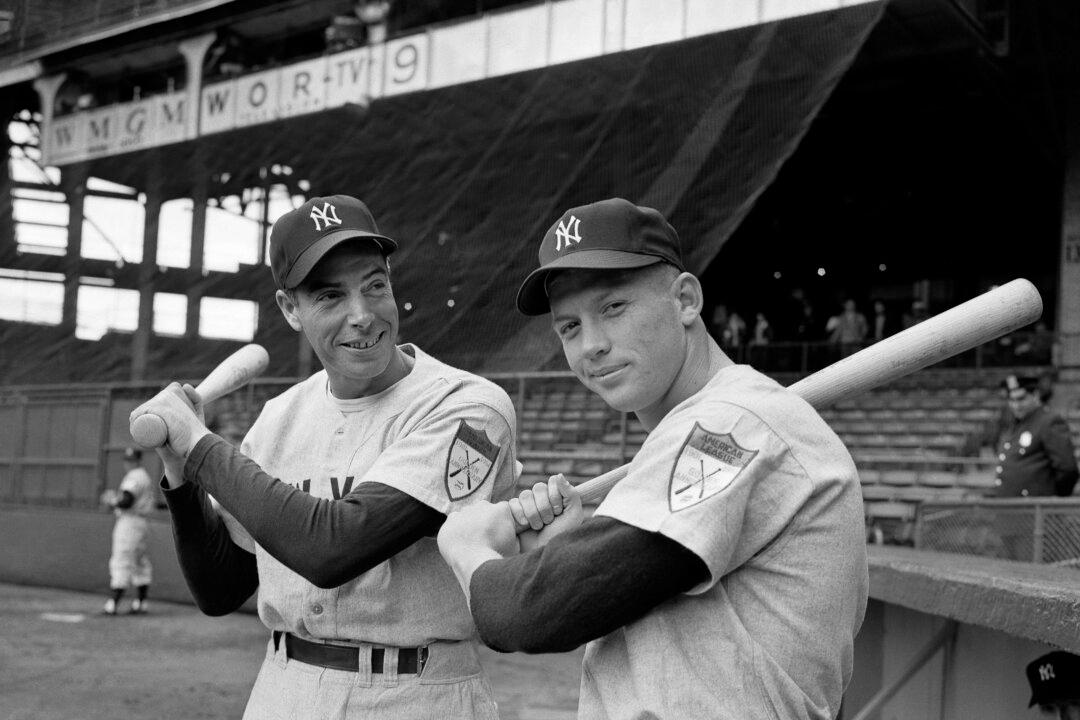

BIG POISON and LITTLE POISON: Paul Waner’s rookie year with the Pittsburgh Pirates was 1926, when he batted .336 and led the league in triples. In one game he cracked out six hits using six different bats. In 1927 the second Waner arrived, brother Lloyd. For 14 years, the Waners formed a potent brother combination in the Pittsburgh lineup. Paul was 5‘8l/2’‘ and weighed 153 pounds. Lloyd was 5’9” and weighed 150 pounds. Paul was dubbed Big Poison even though he was smaller than Lloyd, who was called Little Poison. An older brother even then had privileges. But both players were pure poison for National League pitchers. Slashing left-handed line-drive hitters, the Waners collected 5,611 hits between them. Paul’s lifetime batting average was .333, and he recorded three batting titles. Lloyd posted a career average of .316. They played a combined total of 38 years in the major leagues.

BONEHEAD MERKLE: The phrase “pulling a bonehead play,” or “pulling a boner,” is not only part of the language of baseball, but of all sports and in fact, of the language in general. Its most dramatic derivation goes back to September 9, 1908. Frederick Charles Merkle, a.k.a. George Merkle, was playing his first full game at first base for the New York Giants. It was his second season in the majors; the year before, he had appeared in 15 games. The Giants were in first place and the Cubs were challenging them. The two teams were tied, 1-1, in the bottom of the ninth inning. With two outs, the Giants’ Moose McCormick was on third base and Merkle was on first. Al Bridwell slashed a single to center field, and McCormick crossed the plate with what was apparently the winning run. Merkle, eager to avoid the Polo Grounds crowd that surged onto the playing field, raced directly to the clubhouse instead of following through on the play and touching second base. Amid the pandemonium, Johnny Evers of the Cubs screamed for the baseball, obtained it somehow, stepped on second base, and claimed a forceout on Merkle. When things subsided, umpire Hank O‘Day agreed with Evers. The National League upheld O’Day, Evers and the Cubs, so the run was nullified and the game not counted. Both teams played out their schedules and completed the season tied for first place with 98 wins and 55 losses. A replay of the game was scheduled, and Christy Mathewson, seeking his 38th victory of the season, lost, 4-2, to Three-Finger Brown (q.v.). The Cubs won the pennant. Although Merkle played 16 years in the majors and had a lifetime batting average of .273, he will forever be rooted in sports lore as the man who made the “bonehead” play that lost the 1908 pennant for the Giants, for had he touched second base there would have been no replayed game and the Giants would have won the pennant by one game.

BOO: Name for a day in 1979 of Giants shortstop Johnnie LeMaster, who heard the boo-birds in San Fran. He took his field position wearing “Boo” on his back. LeMaster switched back to his regular jersey after one game.

CAN'T ANYBODY HERE PLAY THIS GAME? In 1960 Casey Stengel managed the New York Yankees to a first-place finish, on the strength of a .630 percentage compiled by winning 97 games and losing 57. By 1962 he was the manager of the New York Mets, a team that finished tenth in a ten-team league. They finished 60 1/2 games out of first place, losing more games (120) than any other team in the 20th century. Richie Ashburn, who batted .306 for the Mets that season and then retired, remembers those days: “It was the only time I went to a ball park in the major leagues and nobody expected you to win.”

A bumbling collection of castoffs, not-quite-ready for-prime-time major league ball players, paycheck collectors, and callow youth, the Mets underwhelmed the opposition. They had Jay Hook, who could talk for hours about why a curve ball curved (he had a Masters degree in engineering) but couldn’t throw one consistently. They had“ Choo-Choo” Coleman, an excellent low-ball catcher, but the team had very few low-ball pitchers. They had “Marvelous Marv” Throneberry, a Mickey Mantle look-a-like in the batter’s box—and that’s where the resemblance ended. Stengel had been spoiled with the likes of Mantle, Maris, Ford, Berra, etc. Day after day he would watch the Mets and be amazed at how they could find newer and more original ways to beat themselves. In desperation—some declare it was on the day he witnessed pitcher Al Jackson go 15 innings yielding but three hits, only to lose the game on two errors committed by Marvelous Marv-Casey bellowed out his plaintive query, “Can’t anybody here play this game?”

CHILI: When he was about 12 years old, Charles Davis was given a not too attractive haircut which led to his getting the nickname “Chili Bowl,” later shortened to “Chili” as the boy became the man and the baseball player “Chili” Davis.

DUGOUT: An area on each side of home plate where players stay while their team is at bat. There is a visitor’s dugout and a home-team dugout. They were originally dug out trenches at the first and third base lines allowing players and coaches to be at field level and not blocking the view of the choice seats behind them.

GIANTS: One sultry summer’s day in 1885, Jim Mutrie, the saber-mustached manager of the New York Gothams, was enjoying himself watching his team winning an important game. Mutrie screamed out with affection, “My big fellows, my giants.” Many of his players were big fellows, and they came to be Giants. For that was how the nickname Giants came to be. And when the New York team left for San Francisco in 1958, Giants, Mutrie’s endearing nickname, went along with it.

JUNK MAN, THE: Eddie Lopat was the premier left-handed pitcher for the New York Yankees in the late 1940’s and through most of the 1950’s. He recalls how he obtained his nickname: “Ben Epstein was a writer for the New York Daily Mirror and a friend of mine from my Little Rock minor league baseball days. He told me in 1948 that he wanted to give me a name that would stay with me forever. ‘I want to see what you think of it—the junk man?’ In those days the writers had more consideration. They checked with players before they called them names. I told him I didn’t care what they called me just as long as I could get the batters out and get paid for it.” Epstein then wrote an article called “The Junkman Cometh,” and as Lopat says, “The rest was history.” The nickname derived from Lopat’s ability to be a successful pitcher by tantalizing the hitters with an assortment of offspeed pitches. This writer and thousands of other baseball fans who saw Lopat pitch bragged more than once that if given a chance, they could hit the “junk” he threw.

ONE-ARMED PETE GRAY: Born Peter J. Wyshner (a.k.a. Pete Gray) on March 6, 1917, Gray was a longtime New York City semipro star who played in 77 games for the St. Louis Browns in 1945. He actually had only one arm and played center field with an unpadded glove. He had an intricate and well developed routine for catching the ball, removing the ball from his glove, and throwing the ball to the infield.

POLO GROUNDS: During the 1880’s, the National League baseball team was known as the New Yorkers. There was another team in town, the New York Metropolitans of the fledgling American Association. Both teams played their season-opening games on a field across from Central Park’s northeastern corner at 110th Street and Fifth Avenue. The land on which they played was owned by New York Herald Tribune publisher James Gordon Bennett. Bennett and his society friends had played polo on that field and that’s how the baseball field came to be known as the Polo Grounds. In 1889 the New York National League team moved its games to a new location at 157th Street and Eighth Avenue. The site was dubbed the new Polo Grounds and eventually was simply called the Polo Grounds. Polo was never played there.

SPLENDID SPLINTER He was also nicknamed the Thumper, because of the power with which he hit the ball, and the Kid, because of his tempestuous attitude—but his main nickname was perhaps the most appropriate. Ted Williams was one of the most splendid players who ever lived, and he could really “splinter” the ball. The handsome slugger compiled a lifetime batting average of .344 and a slugging percentage of .634. Williams blasted 521 career home runs, scored nearly 1,800 runs, and drove in over 1,800 runs. So keen was his batting eye that he walked over 2,000 times while striking out only 709 times. In 1941 he batted .406—the last time any player hit .400 or better. One of the most celebrated moments in the career of the Boston Red Sox slugger took place in the 1946 All-Star Game. Williams came to bat against Rip Sewell and his celebrated “eephus” (blooper) pitch. Williams had already walked in the game and hit a home run. Sewell’s pitch came to the plate in a high arc, and Williams actually trotted out to the pitch, bashing it into the right-field bullpen for a home run. “That was the first homer ever hit off the pitch,” Sewell said later.

“The ball came to the plate in a twenty-foot arc,” recalled Williams. “I didn’t know whether I'd be able to get enough power into that kind of a pitch for a home run.” There was no kind of pitch Williams couldn’t hit for a home run.