The 2016 election has encompassed a breadth of issues—immigration, national security, even Supreme Court politics. But what about the workplace?

Not a single candidate has made it a priority to address labor policy.

Yet the workplace is an integral part of daily life: Americans work almost 35 hours a week on average, longer than their counterparts in the rest of the developed world—Australia comes in second place at 32.4 hours per week. Adults employed full-time report working an average of 47 hours per week. And nearly 40 percent of workers report logging more than 50 hours on the job.

Overall, Americans aged 25 to 54 spend more time working than sleeping or eating.

Yet barely 50 percent of nonunion employees are content with their workplace recognition—that is, the recognition they receive at work for their accomplishments. For union members, that number is an abysmal 35 percent. When barely one-third of union members even feel appreciated on the job, it begs the question: How do we help them?

One place to start is employee rights. It’s not rocket science to suggest that amplifying worker voice might boost workplace satisfaction. Think about it: If union members thought their representatives were truly listening to them, wouldn’t more than 35 percent of them feel appreciated?

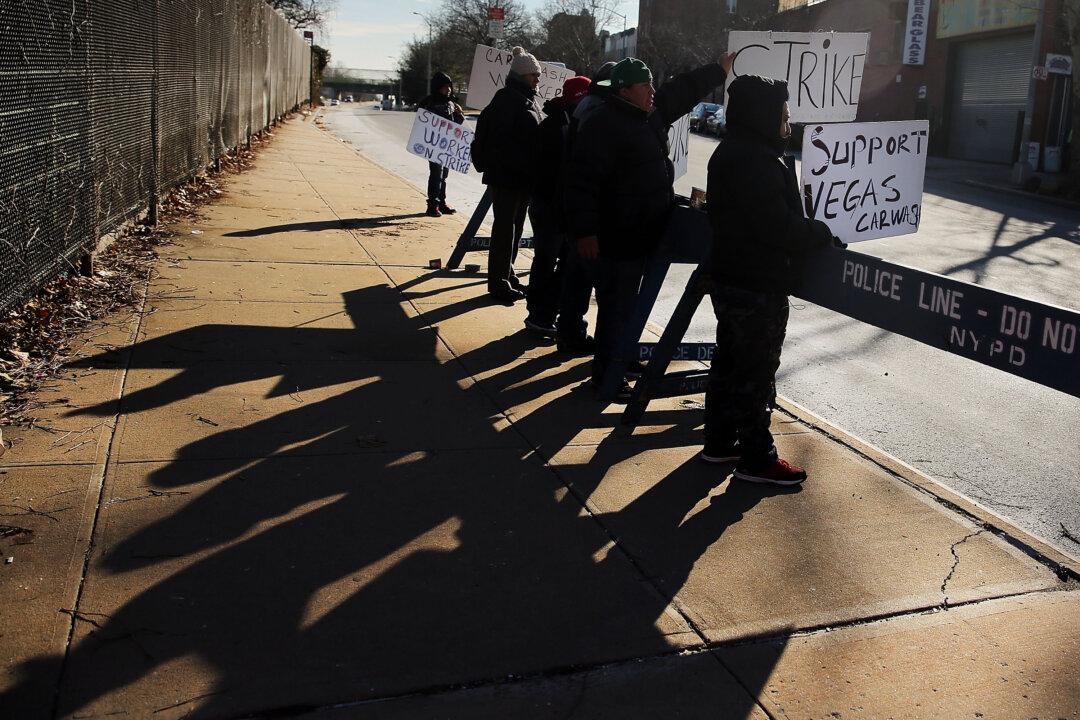

Under current labor law, union members aren’t even guaranteed secret ballot elections—whether they’re mulling union representation or considering a strike vote. In about 40 percent of union recognition “elections,” labor organizers rely on publicly staged “card check” procedures which supplant private votes and circumvent the democratic process. These public sign-up displays leave employees (and employers) vulnerable to union threats, bullying, and other pressure tactics aimed at forcing Big Labor’s agenda on the workforce.