With his only weapons being ingenuity, an authoritative air, a savvy understanding of the enemy, and most of all unflinching courage, Raoul Wallenberg managed to save an estimated 100,000 Hungarian Jews from Hitler’s gas chambers during the waning months of World War II.

The son of a prominent Swedish family of respected bankers, diplomats, and politicians, Wallenberg entered Hungary at the request of the United States War Refugee Board and the Swedish government in July 1944, undercover as a Swedish diplomat.

On January 17, 1945, just six months after he began his mission, Wallenberg was captured by Russian soldiers. He was never heard from again.

This spring marks the 65th anniversary of Wallenberg’s mission to Hungary, and a group of Canadians who have been working to uncover what became of the brave Swede are hoping the mystery surrounding his disappearance will soon be solved.

Wallenberg’s mission was to rescue as many of Hungary’s Jews as possible from Nazi extermination. At the time of his arrival in Budapest there were only 230,000 Jews left; Adolf Eichmann, the so-called architect of the Holocaust, had already sent the other 400,000 to the gas chambers.

In the middle of enemy territory and under the noses of the German soldiers, Wallenberg handed out fake passports he had designed to Jews who were crammed onto trains and on foot in 125-mile “death marches.” They were then hustled to waiting international Red Cross trucks or cars marked in Swedish colours and taken to safe houses.

“He was a great hero of the war and I think that knowing what happened to him would help in remembering what he did,” says David Matas, a Winnipeg-based international human rights lawyer and Wallenberg researcher.

“It’s also simply a matter of justice to him in his memory. I think after he did so much to help so many people we owe it to him and his family to do what we can to help in finding out what happened to him.”

Matas says there’s a “wide variety of conflicting strings of evidence” pointing in many different directions, including that Wallenberg was shot, stabbed, poisoned, or died of a heart attack.

The Russian government has been accused of stonewalling attempts to discover what happened to Wallenberg after his capture and subsequent imprisonment in the notorious Lubyanka prison.

Immediately after the war, the USSR said Wallenberg died in Hungary of a motor vehicle accident, says Matas. Then in 1957 they said he had died in 1947 of a heart attack. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Moscow said he was murdered in 1947 but did not say how.

For years, however, there were numerous reports from former gulag prisoners who claimed to have seen, heard of, or communicated with Wallenberg in various Russian prisons after 1947.

“The Soviet Union has always had a position about Wallenberg. The trouble is the position kept on changing over time and the subsequent position contradicted the earlier position. So it’s just this constant shift of conflicting positions without any real evidence behind any of them,” Matas says.

Matas authored a report on Wallenberg in1998, financed by the Department of Foreign Affairs under then-Foreign Affairs Minister Lloyd Axworthy.

“The conclusion of my report was that the answer to the question of what happened to Wallenberg is not known but it is knowable,” he says.

He found that the primary difficulty in determining Wallenberg’s fate is the inability of independent researchers to access Russian confidential archives.

However, Vladimir Lapchin, senior councilor with the Russian Embassy in Ottawa, says what documentation there is on Wallenberg was made available to researchers in the early 1990s.

“There is nothing new since,” he says. “There are just documents confirming that he was in prison and that’s it. Was he shot, was he executed—there are no documents about this.”

He says allegations of a cover-up by Moscow are unfounded. “People try to find the black cat in the black room even if there is no black cat.”

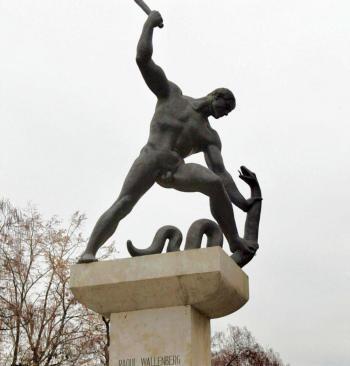

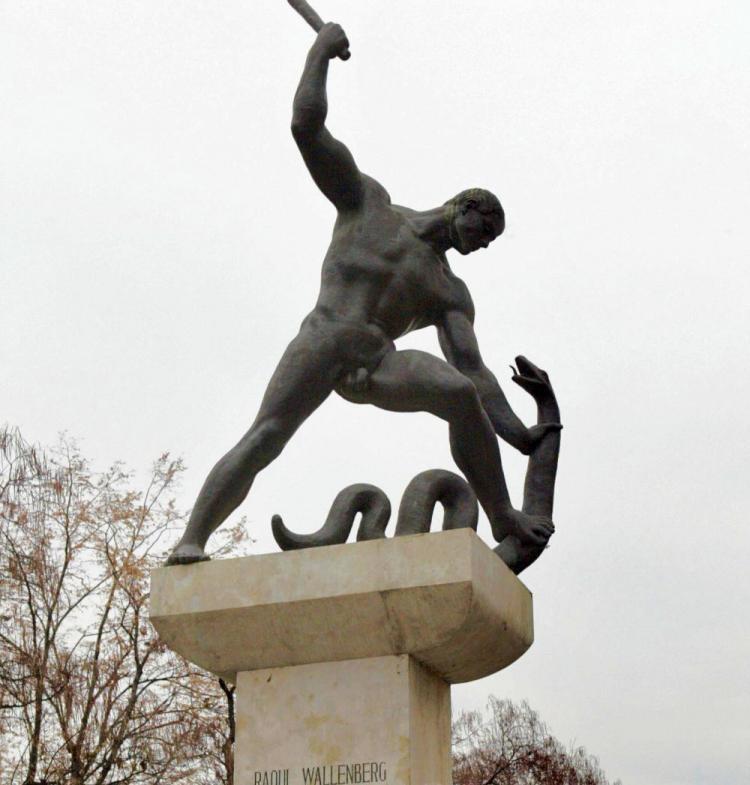

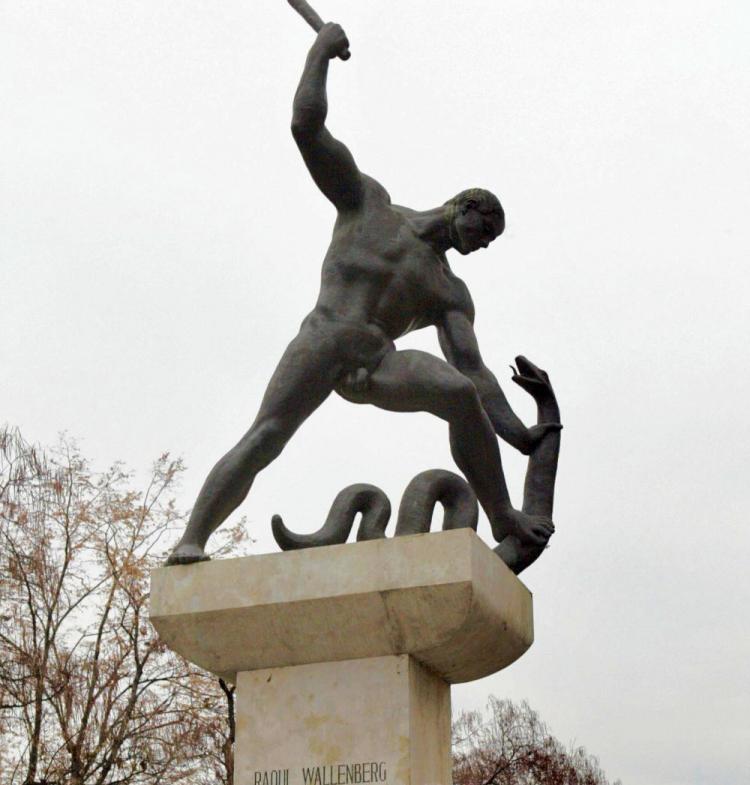

Nominated twice for the Nobel Peace Prize, Wallenberg is an honourary citizen in four countries including Canada and the United States. There are monuments to him in 12 countries while commemorative stamps have been issued in eight. He has also been the subject of numerous books and films.

Canada has declared January 17, the day he disappeared, as Raoul Wallenberg Day, and there are commemorative parks in several Canadian cities. It is largely thanks to Ottawa resident Vera Gara’s efforts that Raoul Wallenberg Park was built in Ottawa.

Gara, herself a survivor of the Nazi death camps, has been involved with the “Wallenberg project” since 1986. She says there’s a new and promising lead currently being investigated.

Wallenberg researchers have asked the Hungarian Embassy for help in obtaining information on three men, one of whom shared a cell with Wallenberg’s assistant in Lefortovo prison prior to 1947.

The other two men worked in the Hungarian resistance movement, which had direct contact with Wallenberg. All three are known to have worked with Wallenberg in Budapest in 1944.

Consular official Imre Helyes said in her reply that “it is possible” the Hungarian National Archive could have some material relating to the three men and that, upon receiving more information, “researchers in the Archive may be able to determine what sources of information may exist there.”

Gara sees this as a positive sign.

“I’m very optimistic,” she says. “My feeling is something is happening, and it has to be now. Quite frankly it has to be now, because there has to be closure on this.”

Speaking at a dinner to commemorate Wallenberg’s heroism in April, Wallenberg researcher and former MP David Kilgour was critical of Hungary, Sweden, and the U.S. for not doing more to find out what became of the war hero.

Wallenberg and his team rescued more than one-third of all Jews saved by the U.S. War Refugee Board, he said. “Until his seizure, he was the board’s best asset. Yet successive U.S. administrations have offered little more than tokenism since 1945 in solving the mystery of his disappearance.”

Kilgour told The Epoch Times that Canada should also be more active in uncovering the truth about Wallenberg’s fate—especially after the incident in which the St. Louis, a ship loaded with Jews fleeing the Holocaust, was not allowed to land on Canadian shores.

“We did so little to help the Jewish people before the war, and in a small way this is what we should be trying to do to try to make up for that terrible injustice [to the people aboard the St. Louis].”

At one point, Wallenberg studied architecture at the University of Michigan, where he was known for his good humour, energy, and “anti-snobism,” according to Kilgour.

During vacations, he hitchhiked around the U.S., Mexico, and Canada. After graduating, he spent some time in South Africa and the Middle East. It was in Palestine (now Israel) that Wallenberg, a Christian, first met Jews fleeing Hitler’s Germany.

Kilgour hopes the mystery of Wallenberg’s fate will be solved while his two siblings are still alive.

“The truth will come out. It’s just whether it’s going to come out before all Wallenberg’s siblings are dead. It would be nice if it could come out now rather than 25 years from now.”

The son of a prominent Swedish family of respected bankers, diplomats, and politicians, Wallenberg entered Hungary at the request of the United States War Refugee Board and the Swedish government in July 1944, undercover as a Swedish diplomat.

On January 17, 1945, just six months after he began his mission, Wallenberg was captured by Russian soldiers. He was never heard from again.

This spring marks the 65th anniversary of Wallenberg’s mission to Hungary, and a group of Canadians who have been working to uncover what became of the brave Swede are hoping the mystery surrounding his disappearance will soon be solved.

Wallenberg’s mission was to rescue as many of Hungary’s Jews as possible from Nazi extermination. At the time of his arrival in Budapest there were only 230,000 Jews left; Adolf Eichmann, the so-called architect of the Holocaust, had already sent the other 400,000 to the gas chambers.

In the middle of enemy territory and under the noses of the German soldiers, Wallenberg handed out fake passports he had designed to Jews who were crammed onto trains and on foot in 125-mile “death marches.” They were then hustled to waiting international Red Cross trucks or cars marked in Swedish colours and taken to safe houses.

“He was a great hero of the war and I think that knowing what happened to him would help in remembering what he did,” says David Matas, a Winnipeg-based international human rights lawyer and Wallenberg researcher.

“It’s also simply a matter of justice to him in his memory. I think after he did so much to help so many people we owe it to him and his family to do what we can to help in finding out what happened to him.”

Matas says there’s a “wide variety of conflicting strings of evidence” pointing in many different directions, including that Wallenberg was shot, stabbed, poisoned, or died of a heart attack.

The Russian government has been accused of stonewalling attempts to discover what happened to Wallenberg after his capture and subsequent imprisonment in the notorious Lubyanka prison.

Immediately after the war, the USSR said Wallenberg died in Hungary of a motor vehicle accident, says Matas. Then in 1957 they said he had died in 1947 of a heart attack. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Moscow said he was murdered in 1947 but did not say how.

For years, however, there were numerous reports from former gulag prisoners who claimed to have seen, heard of, or communicated with Wallenberg in various Russian prisons after 1947.

“The Soviet Union has always had a position about Wallenberg. The trouble is the position kept on changing over time and the subsequent position contradicted the earlier position. So it’s just this constant shift of conflicting positions without any real evidence behind any of them,” Matas says.

Matas authored a report on Wallenberg in1998, financed by the Department of Foreign Affairs under then-Foreign Affairs Minister Lloyd Axworthy.

“The conclusion of my report was that the answer to the question of what happened to Wallenberg is not known but it is knowable,” he says.

He found that the primary difficulty in determining Wallenberg’s fate is the inability of independent researchers to access Russian confidential archives.

However, Vladimir Lapchin, senior councilor with the Russian Embassy in Ottawa, says what documentation there is on Wallenberg was made available to researchers in the early 1990s.

“There is nothing new since,” he says. “There are just documents confirming that he was in prison and that’s it. Was he shot, was he executed—there are no documents about this.”

He says allegations of a cover-up by Moscow are unfounded. “People try to find the black cat in the black room even if there is no black cat.”

Nominated twice for the Nobel Peace Prize, Wallenberg is an honourary citizen in four countries including Canada and the United States. There are monuments to him in 12 countries while commemorative stamps have been issued in eight. He has also been the subject of numerous books and films.

Canada has declared January 17, the day he disappeared, as Raoul Wallenberg Day, and there are commemorative parks in several Canadian cities. It is largely thanks to Ottawa resident Vera Gara’s efforts that Raoul Wallenberg Park was built in Ottawa.

Gara, herself a survivor of the Nazi death camps, has been involved with the “Wallenberg project” since 1986. She says there’s a new and promising lead currently being investigated.

Wallenberg researchers have asked the Hungarian Embassy for help in obtaining information on three men, one of whom shared a cell with Wallenberg’s assistant in Lefortovo prison prior to 1947.

The other two men worked in the Hungarian resistance movement, which had direct contact with Wallenberg. All three are known to have worked with Wallenberg in Budapest in 1944.

Consular official Imre Helyes said in her reply that “it is possible” the Hungarian National Archive could have some material relating to the three men and that, upon receiving more information, “researchers in the Archive may be able to determine what sources of information may exist there.”

Gara sees this as a positive sign.

“I’m very optimistic,” she says. “My feeling is something is happening, and it has to be now. Quite frankly it has to be now, because there has to be closure on this.”

Speaking at a dinner to commemorate Wallenberg’s heroism in April, Wallenberg researcher and former MP David Kilgour was critical of Hungary, Sweden, and the U.S. for not doing more to find out what became of the war hero.

Wallenberg and his team rescued more than one-third of all Jews saved by the U.S. War Refugee Board, he said. “Until his seizure, he was the board’s best asset. Yet successive U.S. administrations have offered little more than tokenism since 1945 in solving the mystery of his disappearance.”

Kilgour told The Epoch Times that Canada should also be more active in uncovering the truth about Wallenberg’s fate—especially after the incident in which the St. Louis, a ship loaded with Jews fleeing the Holocaust, was not allowed to land on Canadian shores.

“We did so little to help the Jewish people before the war, and in a small way this is what we should be trying to do to try to make up for that terrible injustice [to the people aboard the St. Louis].”

At one point, Wallenberg studied architecture at the University of Michigan, where he was known for his good humour, energy, and “anti-snobism,” according to Kilgour.

During vacations, he hitchhiked around the U.S., Mexico, and Canada. After graduating, he spent some time in South Africa and the Middle East. It was in Palestine (now Israel) that Wallenberg, a Christian, first met Jews fleeing Hitler’s Germany.

Kilgour hopes the mystery of Wallenberg’s fate will be solved while his two siblings are still alive.

“The truth will come out. It’s just whether it’s going to come out before all Wallenberg’s siblings are dead. It would be nice if it could come out now rather than 25 years from now.”