Many countries try to make their products more competitive in international markets. Some subsidize exports directly and indirectly (China), some have very lax labor laws (Bangladesh), some devalue their currency (Europe, Japan), and some do all of the above just to boost exports and discourage imports.

The United States has engaged in currency wars with Europe, China, and Japan and devalued the dollar during the Federal Reserve’s quantitative easing programs after 2009. It didn’t help much to close the trade deficit.

This is why President Donald Trump is now proposing a more radical concept: the border adjustment tax, or BAT. True to its name, the BAT would adjust the price for both exports and imports, but would do so through corporate taxes.

Imports

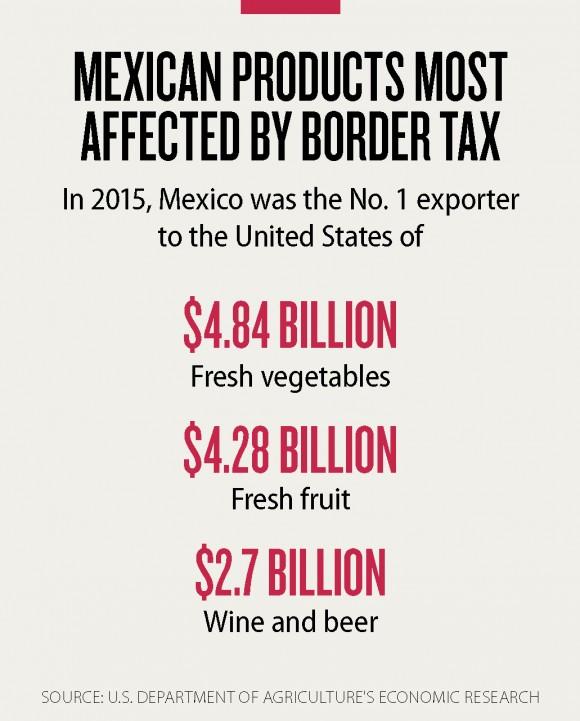

Under the BAT plan, importers of Mexican or Chinese goods, for example, would pay a 20 percent tax on merchandise sold in the United States, making products like tequila, fresh fruit, and iPhones more expensive, although it is not yet clear which countries would be affected. Trump indicated that the tax could be levied on Mexico to pay for the southern border protection wall.

Importers would try to pass on the tax to consumers if they could, leading to a rise in domestic prices. All other things being equal, the 20 percent import tax proposed would raise the consumer price index by about 5 percent, according to Deutsche Bank calculations.

However, consumers would have a choice: They could either pay much higher prices for the imported products they have gotten used to, if there isn’t a domestic replacement (think Louis Vuitton bags); or they could switch to local products, which may be only slightly more expensive, in the case of domestically produced fruits and vegetables. The importers may also decide to pass on only part of the tax, leaving consumers only a little bit worse off.