The Los Angeles Times headline reads, “Oil Glut, Price Collapse Spreads Across World Economies: As producers squirm, other nations rejoice.” That headline describes the current situation perfectly, but it appeared on March 2, 1986—almost three decades ago.

In a story published days later, Los Angeles Times reporter Don Cook stated, “The critical issue ... is the outright state of economic warfare declared by the Saudis.” Events leading up to these stories were remarkably similar to those of today.

The oil glut started building in the early 1980s when soaring oil prices drove expanded non-OPEC production and weakened demand. Slowing economic activity in industrialized countries exacerbated the glut. Efforts by the Saudis to tighten markets were stymied as other OPEC members habitually failed to adhere to their allocated quotas, leaving the kingdom as the sole swing producer.

After five years of seeing their market share drop, the Saudis had enough. Within hours of Oil Minister Sheik Ahmed Zaki Yamani’s vow to end the erosion of his country’s market share, prices plummeted from $30/barrel to below $10. It would be almost 20 years later, in 2005, before real (inflation-adjusted) oil prices finally climbed back to pre-collapse levels.

I stepped down as founding CEO of EnCana Corporation in 2005, also the year that, after three decades dedicated to the building of the company into Canada’s largest oil and gas producer. The 1980s price collapse had taught me the importance of building our company’s asset base upon resources having the lowest possible development and operating costs. Even as oil prices hit $60/barrel, we were still using a price of half that amount to test the financial resiliency of our development projects.

Since retiring, I’ve watched in amazement as oil prices continued their climb to over $100/barrel. Even more amazing has been the mandating of so many projects requiring sustained high oil prices to be economically viable. Were the lessons of the 1980s forgotten in a euphoric cash-rich drive for growth? Or could it be that the current generation of industry leaders aren’t old enough to have experienced those lessons?

The last time the Saudis became fed up with diminishing market share, it took 20 years for oil prices to recover. Then they doubled again to more than to over $100/barrel in the next eight years. No one knows if such high prices will ever be seen again, but projects based on the higher quality resources can achieve good investment returns at much lower price levels.

Rather than risking shareholder capital on projects needing unsustainably inflated prices to be financially viable, prudent forecasting and cost discipline will need to rule. This reality will drive a fundamental sorting out of industry players based on the quality of their assets and technological expertise.

Those with projects that can yield acceptable risk-adjusted returns at prices at the lower end of the scale will gain investor support, while the owners of higher cost assets pray for salvation from the Saudis. That’s an unlikely prospect because putting the fear of high oil price forecasts into the industry’s psyche is precisely the Saudi’s goal.

Longer term, there’s one factor that ensures a strong future for oil producers. Every barrel produced must be replaced if global production is to be sustained. Tomorrow morning, there will be 94 million fewer barrels of oil than existed this morning. And despite moderating demand among industrialized countries, the International Energy Agency (IEA) forecasts developing world growth will drive global demand to 120 million barrels per day by 2040, while the current global capacity surplus is only 4 million barrels per day.

No one knows how long it will take, but the coming corporate player retrenchment combined with global demand growth will, once again, see the Canadian oil sector humming. It will be a stronger, more resilient industry. And just maybe, history lessons will have become compulsory.

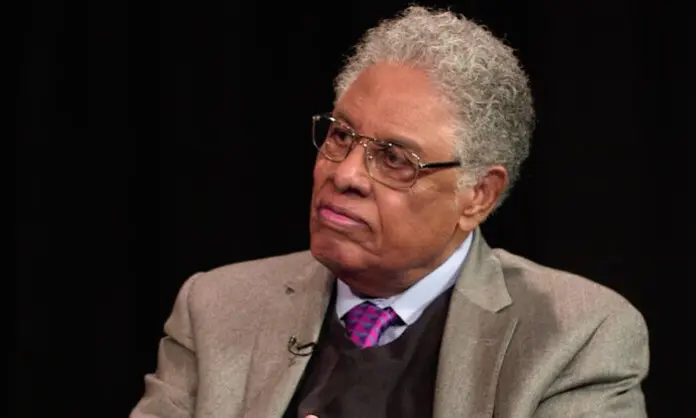

Gwyn Morgan is a retired Canadian business leader who has been a director of five global corporations. This article previously published on TroyMedia.com.

Opinion

We Should Have Seen an Oil Price Collapse Coming

An oil well owned an operated by Apache Corporation in the Permian Basin in Garden City, Texas, on Feb. 5, 2015. Spencer Platt/Getty Images

|Updated:

Gwyn Morgan devoted three decades to building North America’s leading oil and gas company. When he stepped down as founding CEO in 2006, EnCana Corporation had an enterprise value of approximately $60 billion. Gwyn has served as a director of five global corporations including HSBC. He was appointed a Member of the Order of Canada in 2011.

Author’s Selected Articles