Most times of the year it’s a cute quiet place in Northern Bavaria—normal life, normal people, but when the Wagner Festival starts, life itself becomes theater—you will find laurel wreaths for Wagner in the backyard of his villa and next to his gravestone a little one reading: “Here rests and wakes Wagner’s dog” with a little bone with a red bow decoration.

People will scramble in front of the box office to get one of the few returned tickets or pay black market prices to get into the holy hall.

They will endure up to five hours of sitting on bare wooden or spartanly upholstered seats to watch a performance. They will jump into their suits at the parking lot after driving hundreds of kilometers just to see a second or third act of Tristan and Isolde.

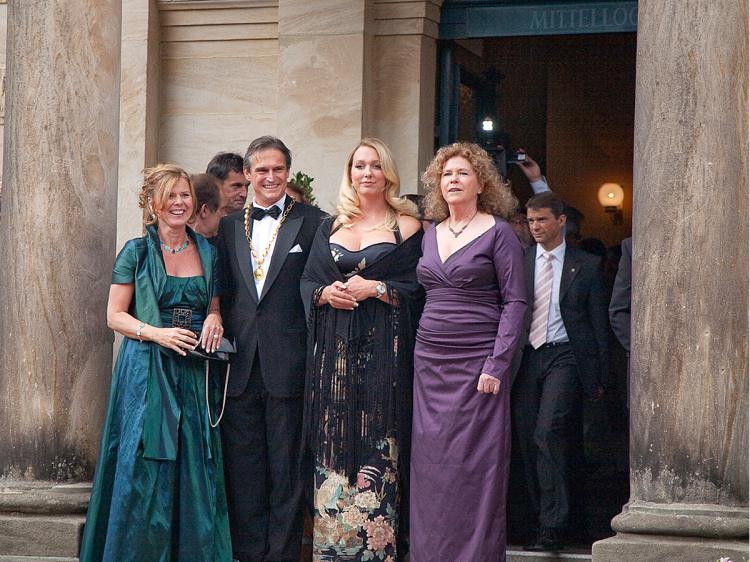

Last Saturday the hype began again, starting with the arrival of the VIPs at the Bayreuth Festival Theater House, nicknamed the “Green Hill.” Crowds of Bayreuth citizens with their families plus a decent army of media people gathered beside the red carpet. The attraction of the year was that after 57 years of chairing the event, grandson of the composer Wolfgang Wagner passed the position to his daughters Katharina (31) and Eva Wagner-Pasquier (64). The applause for the Wagner sisters was big but also a gesture of local patriotism—a little bit scary.

While Bayreuth has seen glorious days especially from the 50s to the 80s, its artistic star began to sink in the mid 90s, when old Wolfgang tried to keep the festival trendy by inviting avant-garde and much debated people to work there—including Heiner Müller, Christoph Marthaler (who directed this opening night Tristan) and Christoph Schlingensief—directors that were in vogue in spoken theater and film, but had never done operas before.

The pressure to be an innovative world leader has done some harm to the mother of all festivals, which was founded by Richard Wagner as an independent alternative to the repertoire opera business of his time.

The decision to keep the chair in the family has been much debated, as critical voices believed that it would be better for the artistic quality of the festival not to be run by the Wagner heirs—as the whole quarrel of the successorship has shadowed the splendor of the festival.

“I think the decision was more a politically than an artistically motivated one,” said Alexander Ehlers, a lawyer from Munich and member of the Friends of Bayreuth who are one of the festivals financial sponsors. “I personally thought of Bayreuth always as something solely dedicated to the arts. Now it shall become a brand—I have the feeling that it is now more an issue of commercializing an idea—and that’s not very thrilling to me.”

“I loved Wagner from my childhood on,” he said. And that’s why they are here. The question if Katharina and Eva will get the festival back on track to its old splendor could make you melancholic—but people came here to listen to the music and to dream of a better world.

Anna Wild, a doctor of medicine from Bayreuth explained the special fascination. “That’s the complete artwork, the maximum effort of the artists. The music that because of the acoustics is nowhere more beautiful than here,” she said.

Willi Bergmann, ex-banker from Munich, who was so enchanted by the Bayreuth flair, said that he and his wife had almost forgotten about modern directing. “The atmosphere, the acoustics, the impression. The audience is different from ordinary operas—it’s very quiet during the performance.”

Later at the state reception at Neues Schloss in the city, host Bavarian Minister-President Horst Seehofer thanked Wolfgang Wagner (who didn’t attend the event) and called his era as festival leader an “undoubtedly grand, formative and splendid” one.

Katharina and Eva were standing with him on the podium, but didn’t take the chance to speak—although the guests were mainly employees of the festival and the city of Bayreuth together with their families.

Far more talkative were the guests, included the VIPs who were eagerly giving interviews while drinking and eating:

German Minister of Economics Guttenberg called the Marthaler directing of Tristan und Isolde an arguable yet touching directing.” The Minister of Cultural for Great Britain Ben Bradshaw said, he especially liked “the 50s-like prudery of the illustration.”

Not prudish at all was the comment of chanteuse and former Munich state ballet dancer Margot Werner (an old Bayreuth fan) she praised the vocal quality of American tenor Robert Dean Smith who sang, “Especially in the third act tremendously beautiful.” Irene Theorin as Isolde as well as conductor Peter Schneider received high marks from her. But regarding the stage setting, the diva said, “Here I don’t want to say anything. You can’t bring a love act on stage like this. You can’t do that—That’s taking people’s illusions—Tristan in the bed of a psychiatric hospital—I don’t want to see that.”

The last smashing insight of the evening was the unintentional comment of an insider who affirmed the rumor of what a cleaning lady had already mentioned to me in the afternoon—a certain hero keeps on singing although his voice is in decline … that’s because an affair with guess who years ago brought him a contract over several seasons—and now they can’t get rid of him. And that’s Bayreuth, too.