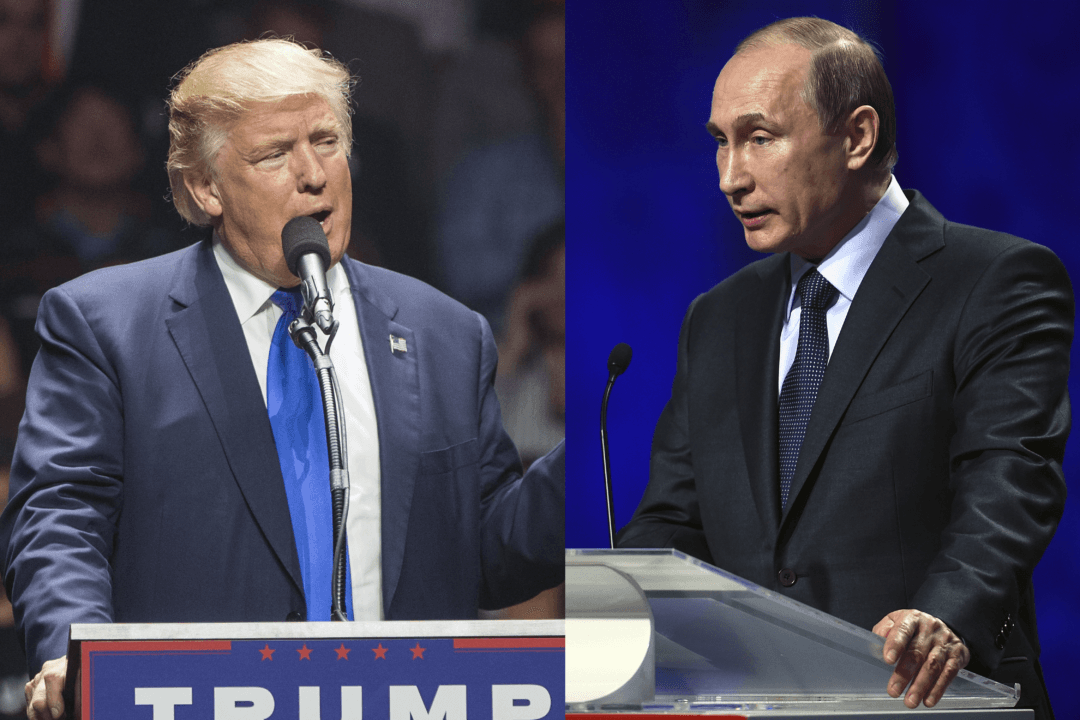

Shortly after Donald Trump was announced as the U.S. president-elect on Nov. 9, Russian President Vladimir Putin sent his congratulations, and shared his hope that he and Trump could “work together to lift Russian–U.S. relations out of the current crisis.”

Days later, on Nov. 14, Trump and Putin had a phone call, during which they “expressed support for active joint efforts to normalize relations and pursue constructive cooperation on the broadest possible range of issues,” according to a Kremlin press release.

While Trump and Putin may share the wish to repair ties between their countries, doing this will likely be a difficult and delicate process.

“The risks of mistakes or miscalculations in U.S.–Russia and NATO–Russia relations are unacceptably high,” said Sir Adam Thomson, director of the European Leadership Network, a London-based think tank focused on defense and security issues.

Thomson, who is a former British ambassador to NATO, believes that improved U.S.–Russia ties could on both sides mean “greater prosperity, lower defense costs, more collaboration on shared regional problems, and less NATO–Russia tension.”

He said in an email this issue is pressing because “the confrontation since Russia annexed Crimea is arguably more dangerous than at any time since the 1960s.”

“But it depends how it’s done,” he said. “Nervous European allies wouldn’t thank future President Trump for deciding matters affecting NATO over their heads. Russians would want constraints on what they perceive as U.S. interventionism.”

The diplomatic situation for the two nations could easily fall back to where it was in the 2000s, Thomson said, and there is a large gap between what each side regards as “acceptable behavior.”

“There’s no magic wand to wave to make this better and no alternative to the painstaking rebuilding of trust, transparency, and accountability,” he said. “Sloppy diplomacy in the short term could only lead to greater mutual unhappiness later.”

According to James Carden, executive editor for the American Committee for East-West Accord, even if Trump and Putin share a hope to repair relations and build closer ties, several external factors could easily derail their efforts.

“I think that it is not entirely realistic to think that Trump will be able to singlehandedly pursue a detente with Russia,” said Carden, who is also a former adviser to the U.S.-Russia Presidential Commission at the U.S. State Department, in an email.

Many people within Trump’s team—including his CIA chief, Rep. Michael Pompeo, his national security adviser, Gen. Michael Flynn, and his deputy national security adviser, K.T. McFarland—seem to be in favor of discarding the Iran nuclear deal.

That would “greatly upset the Russian government, which has close ties to Iran and is a signatory to the deal,” said Carden, noting some on Trump’s team, such as Flynn, may otherwise support closer U.S.–Russia ties.

According to Fred Harrison, an economist and author who worked to transition Russia to a free economy near the fall of the Soviet Union, Trump’s views “aren’t aligned with what his closest aides seem to be preferring ... which is to be hostile to Russia and most of its friends in the Middle East.”

This ties to a deeper problem, which Thomson, Carden, and Harrison pointed out: The United States and Russia are on different sides of very divided global alliances. The United States is backing NATO troop deployments along the Russian border, has many disputes with Iran, and is backing rebel forces in Syria, for example. Russia, meanwhile, is opposing NATO troops deployed along its border, has close ties with Iran, and is backing Syrian government forces who are fighting the rebels.

Efforts between Trump and Putin to build closer ties will likely hit on each side’s sensitive policies with other nations.

Carden believes Trump will have trouble pulling out of engagements started under President Barack Obama, just as Obama found himself stuck with engagements started by former President George W. Bush, such as the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.