For a Dozen American Carpenters and Wood Enthusiasts on an 11-day Tour of Switzerland, the Best Sights Are Well Off the Beaten Track.

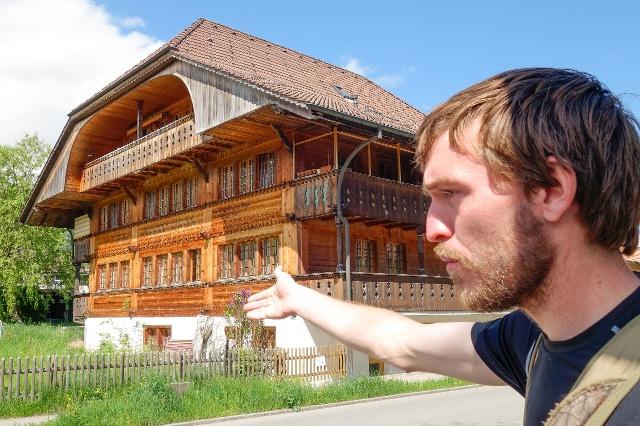

“That’s one – that’s one of the buildings!” grins David Bähler, visibly tickled to see the handiwork of one of his ancestors. The timber framed house from the 1700s is adorned with geraniums, cowbells and red gingham curtains. In other words, it couldn’t look much more Swiss.

Bähler is a 26-year-old carpenter from Indiana in the American Midwest, but his roots are in canton Bern. He’s a member of the fourth generation of Swiss descendants born in the US after his forebears – Anabaptists – fled for religious as well as economic reasons.