LONDON—Prime Minister David Cameron sought Monday, July 20, to dissuade young Muslims from joining the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS), saying they would only become “cannon fodder.”

Cameron announced new powers designed to put those who radicalize young people “out of action,” together with plans to allow parents to cancel their children’s passports to prevent them from traveling abroad to join a radical group. The measures are meant to crush the infrastructure that has made it possible for as many as 700 young Britons to join radicals abroad, he said.

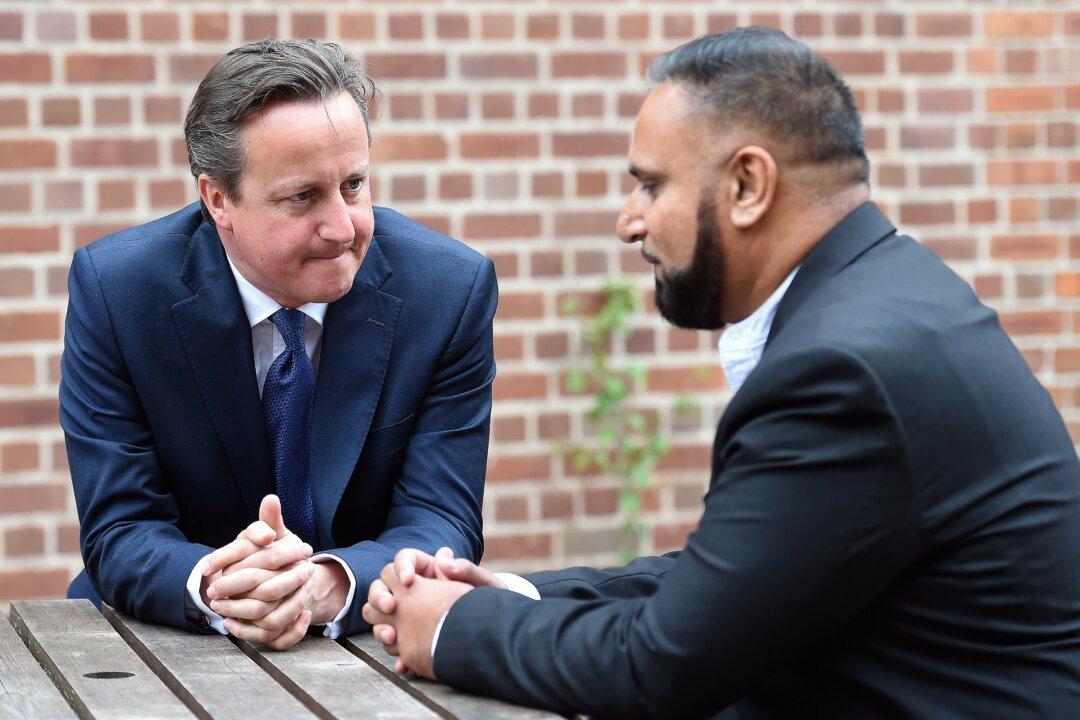

In a wide-ranging speech that targeted the ideology of extremism, Cameron chose a school in Birmingham, a center of the Muslim community in Britain, to argue that it was time to counter the narrative that has attracted so many young people to the ISIS group, also known as ISIL. Britain must “de-glamourize” such groups by making the young aware of the stark reality of life under their control, he said.