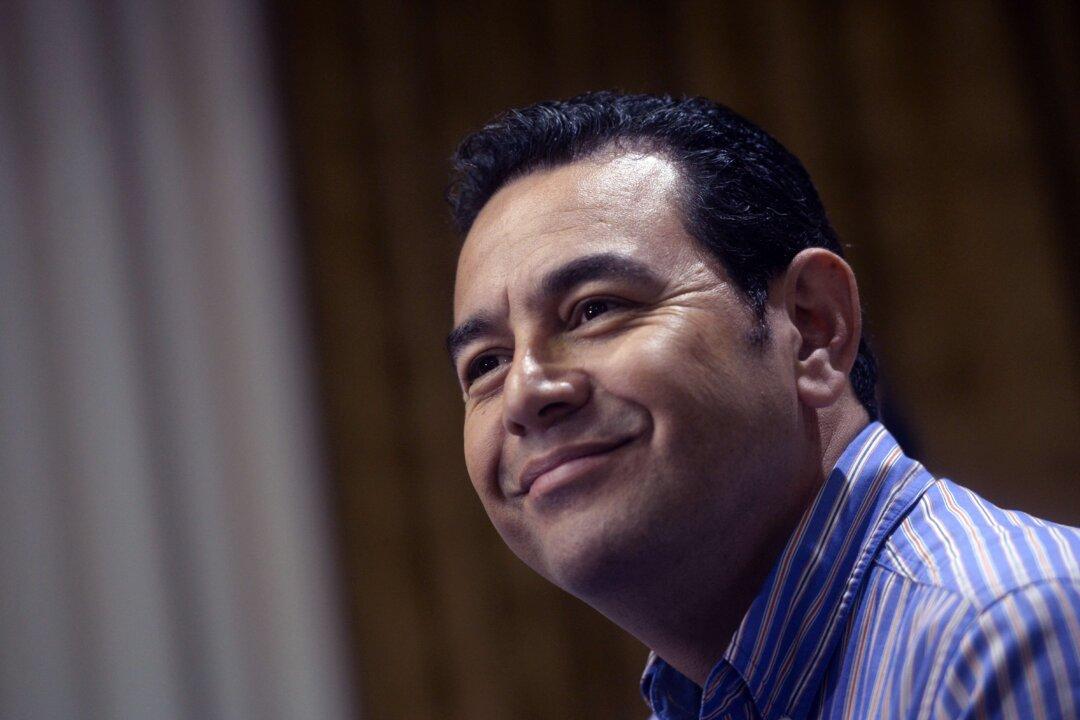

GUATEMALA CITY—Now that former comedian Jimmy Morales has ridden a tide of voter frustration to win Guatemala’s presidency, it remained unclear Monday about what political neophyte might do once in office.

So far he’s given few clues, beyond hinting at reviving a dormant border dispute with neighboring Belize, or attaching GPS locating devices to teachers to ensure they’re in class.

Morales’ campaign was heavy on style and light on concrete policy proposals and as landslide vote numbers rolled in on Sunday night, his campaign headquarters looked a lot like a TV variety show, with a band and dancers.

His biggest campaign pledge—like that of nearly all other candidates—was to fight the entrenched corruption that forced the resignation of his predecessor, Otto Perez Molina, but Morales has spoken little about his own party’s ties to some of the most conservative sectors of Guatemala’s military, which has been struggling to avoid being held accountable for massacres committed during the country’s 1960-1996 civil war.

“Jimmy Morales has no concrete plans to fight corruption, or anything else, for that matter. He just doesn’t have any,” said political analyst Renzo Rosal, who thinks the average voter went for Morales because “it’s better to have him, than the other gang of thieves.”

He predicted that Morales, whose nationalistic National Convergence Front won few seats in Congress, will wind up cobbling together alliances with the very ruling elite that was targeted by mass anti-corruption protests this summer.

National Convergence itself was founded by retired army officers, some of whom have been implicated in rights abuses during the 1960-1996 civil war that pitted the army against leftist guerrillas. Former military dictator Efrain Rios Montt is fighting genocide charges for his role in the conflict, in which 200,000 died.

Morales has sought to distance himself from the officers who founded the party, but one of them, Col. Edgar Ovalle, was a close campaign adviser and will head the party’s tiny, 11-member contingent in the 158-seat Congress.

Morales caused alarm in neighboring Belize, which has had a long territorial dispute with Guatemala, when he appeared on a television cooking show and said, “We are on the point of losing Belize.”

As he concentrated on chopping a tomato, Morales told host Beatriz Colmenares that Guatemala can still go to international courts where “we can fight for that territory, or at least a part of that territory,” though he clearly was speaking only of diplomatic action.

“It seems like a joke,” political analyst Carlos Mendoza said of reviving the border conflict. “He has to start showing he’s serious, and that starts with putting together a professional governing team that doesn’t have any stains on its honor.”

The 46-year-old Morales, who is to assume the presidency Jan. 14 and has never held political office, said he would work with a transition team to study economic issues and work on development-oriented policies.

Officials results showed him winning around 68 percent of the votes with 97 percent of polling stations tallied, swamping the vote total of former first lady Sandra Torres, who conceded defeat.

Morales’ own comments on the campaign trail have left some wondering whether to take seriously everything he says.

Until this year he was perhaps best known for TV skits portraying him in blackface or Indian garb, and he appears in no hurry to let people forget his past as a comedian.

“For 20 years I have made you laugh,” he said. “I promise that as president I won’t make you cry.”

His skits—some of which feature him speaking in a bumbling, fake Indian accent—didn’t leave everyone in this majority-Indian country laughing.

“Jimmy Morales has made a lasting contribution to prejudice and the image of the inferiority of Indians,” said Indian congressman Amílcar Pop, who said the comedian could get away with such skits and still get elected president only because Guatemala “is awash in deeply rooted racism.”

The runoff came a month and a half after Perez Molina resigned and was jailed in connection with a sprawling customs scandal. His former vice president has also been jailed in the multimillion-dollar graft and fraud scheme.

Alejandro Maldonado Aguirre, who replaced Baldetti as vice president after she resigned, assumed the country’s top job when Perez Molina quit.

Though the street protests have died down since Perez Molina’s resignation, many Guatemalans remain fed up with corruption and politics as usual, and Morales will face pressure to deliver immediately on demands for reform.

During his campaign, Morales promised to keep Attorney General Thelma Aldana, a key figure in the investigation, as well as a U.N. commission that was key to unravelling the scandal. He also vowed to strengthen oversight of government agencies.

Election officials and international observers said the vote came off without violence.

“They were very calm elections,” said Juan Pablo Cordazzoli, chief of the Organization of American States observer mission. “There were no serious incidents like in the first round.”