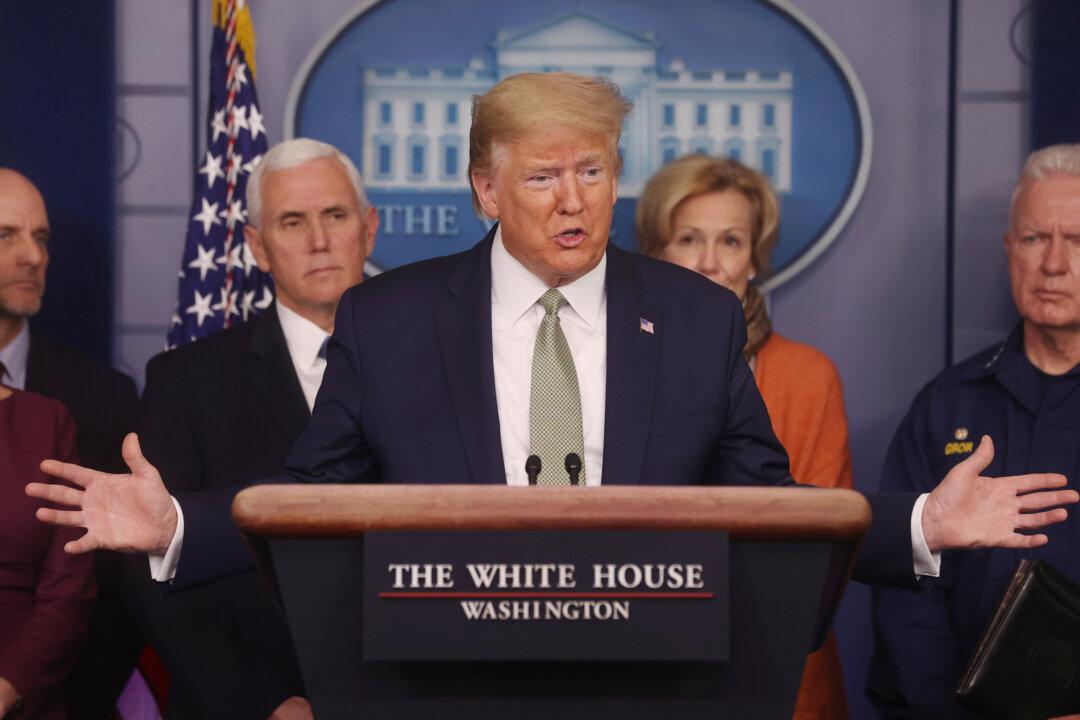

President Donald Trump focused attention on possible treatments for the new coronavirus on Thursday, citing potential use of a drug long used to treat malaria and some other approaches still in testing.

At a White House news conference, Trump and Food and Drug Administration Commissioner Dr. Stephen Hahn cited the malaria drug chloroquine, along with remdesivir, an experimental antiviral from Gilead Sciences, and possibly using plasma from survivors of COVID-19, the disease the new virus causes.