We cannot know where the next deadly health threats will come from, according to the top Centers for Disease Control and Prevention official. There are three top health dangers, said Tom Frieden, head of the CDC.

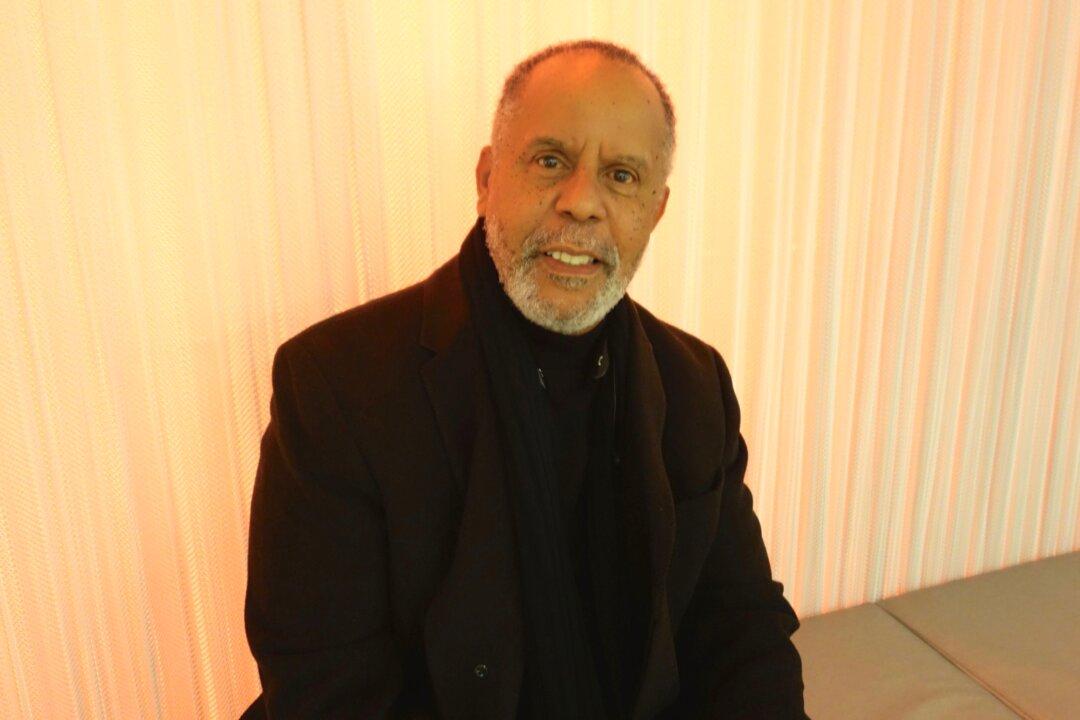

Emerging infectious diseases are health threat number one. “On average, one new (disease) organism is found every year, said Friedan. He spoke on June 1 at the 4th Atlanta Summit on Global Health in Latin America and the Caribbean, hosted by the Word Affairs Council of Atlanta. ”It can come from anywhere. No one expected the first pandemic of the 21st century to come from Mexico, but it did, H1N1 influenza.”

The second is antibiotic resistance. As many doctors have warned, we are in danger of entering a post-antibiotic world. Freiden, a doctor, said he has treated patients for whom it is already a post-antibiotic world. Those patients had “organisms that responded to no antibiotics.” Changes in how antibiotics are used in medicine and in the food supply are essential.

The third health threat was even more nightmarish, and combined the first two, new organisms and antibiotic resistance. “Intentionally created organisms,” might be used as weapons, said Friedan, or might be genetically engineered with good intentions and then run amok.

Preparing

“Ebola was a reminder that the next thing we face is probably not going to be the thing we’re preparing for, and that’s why it’s so important that we prepare the system,” he said.

The way to prepare for the unimaginable is to strengthen global health systems, according to Frieden. It is also necessary to strengthen indigenous health systems. He said the world has to be able to surge and help a region that is overwhelmed by a health crisis. This is true, and the countries in West Africa needed outside help to contain the 2014-2015 Ebola outbreak.

But a surge is not always an intelligent surge. A June 3 ProPublica story that said the American Red Cross failed to help people in Haiti after the earthquake made me think of how outside surges can go wrong. According to the story, one of its key mistakes was failing to hire local people for its projects. They would have known local conditions, laws, needs, customs, and languages. But Red Cross officials discounted them.

Dr. Virginia Floyd of Morehouse School of Medicine asked one of the panels of doctors and officials at the summit how much they work with local traditional healers and lay midwives in Latin America. In order to reach people effectively, it is essential to understand and respect health care structures that already exist. Some of the doctors said they did work with local healers, and noted how valuable it is to do that. As trusted members of the community, they are ideal conduits for health information.

During lunch, she said that she began to study traditional healers, expecting to debunk them. She said she was humbled and inspired when she found she could learn from them.

With a W. K. Kellogg Foundation National Leadership Fellowship grant, Floyd studied traditional medicine in Africa, Latin America, and the Caribbean, and in Native American nations here. “The first thing I learned is how poorly trained I am as a healer. I am a good technician, but I don’t have a clue about healing your soul. It has brought me full circle ... Through my studies, I’ve realized that indigenous knowledge is true science,” she said, in her biography on the National Institutes of Health web site.

Any surge and any health education program must flow both ways, with respect and compassion.