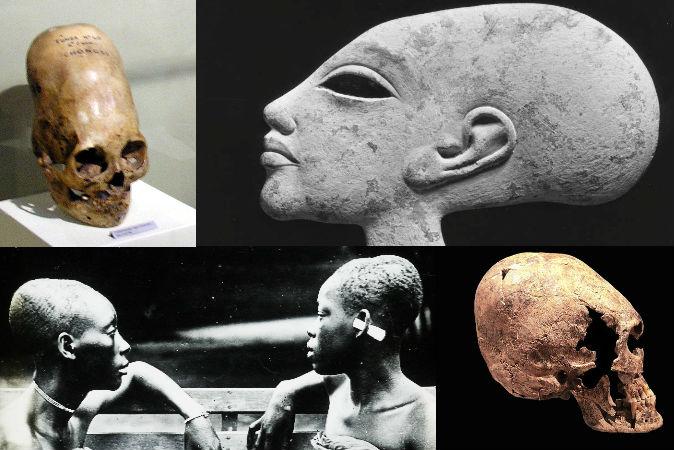

Elongated skulls have been found in ancient burial grounds around the world. Many are the result of a practice of intentionally deforming the skull with binding applied during the early years of a child’s life. Some may be explained by natural deformity. Yet enough mystery is left in relation to some of the skulls for various theories to arise.

Could the elongated skulls in Paracas, Peru, for example, come from a human-like species never before studied?

Paracas, Peru

A case of skulls from the Andean Paracas culture, as seen in the National Museum of the Archaeology, Anthropology, and History of Peru. (Wikimedia Commons)

Some of the most famous elongated skulls are those found in Paracas on the coast of Peru. The skulls are believed to be from 3,000 to 2,000 years old.

Brien Foerster, assistant director of the Paracas History Museum in Paracas, announced in February that a geneticist analyzed the first flesh sample from the skulls and found that segments of its DNA do not match any known human or human-like species from the past.

The results are preliminary, and Foerster said he made the announcement to gain public interest, and thus funding to continue analysis on more samples.

Though Foerster did not name the geneticist, he said this geneticist is in the United States, has all the right credentials, and does contract work for the American government.

Foerester has taken a keen interest in elongated skulls and done much independent research over the years. He told Ancient Origins in a taped interview (see below) in February that about 5 to 10 percent of the hundreds of elongated skulls he has seen from around the world do not appear to be the result of intentional deformation. The binding techniques usually leave a flattened surface on part of the skull, but some of the skulls he has seen appear quite natural.

Foerster’s credibility has been questioned by some. He does not appear to have an advanced degree or formal archaeological training. Though he is the assistant director of the Paracas History Museum, this is a privately owned museum, and some point out that it stands to gain from the publicity.

Epoch Times will be waiting to hear more, and perhaps further DNA testing and public testimonial from geneticists will shed more light on the matter.

Egypt’s Pharaoh Akhenaten

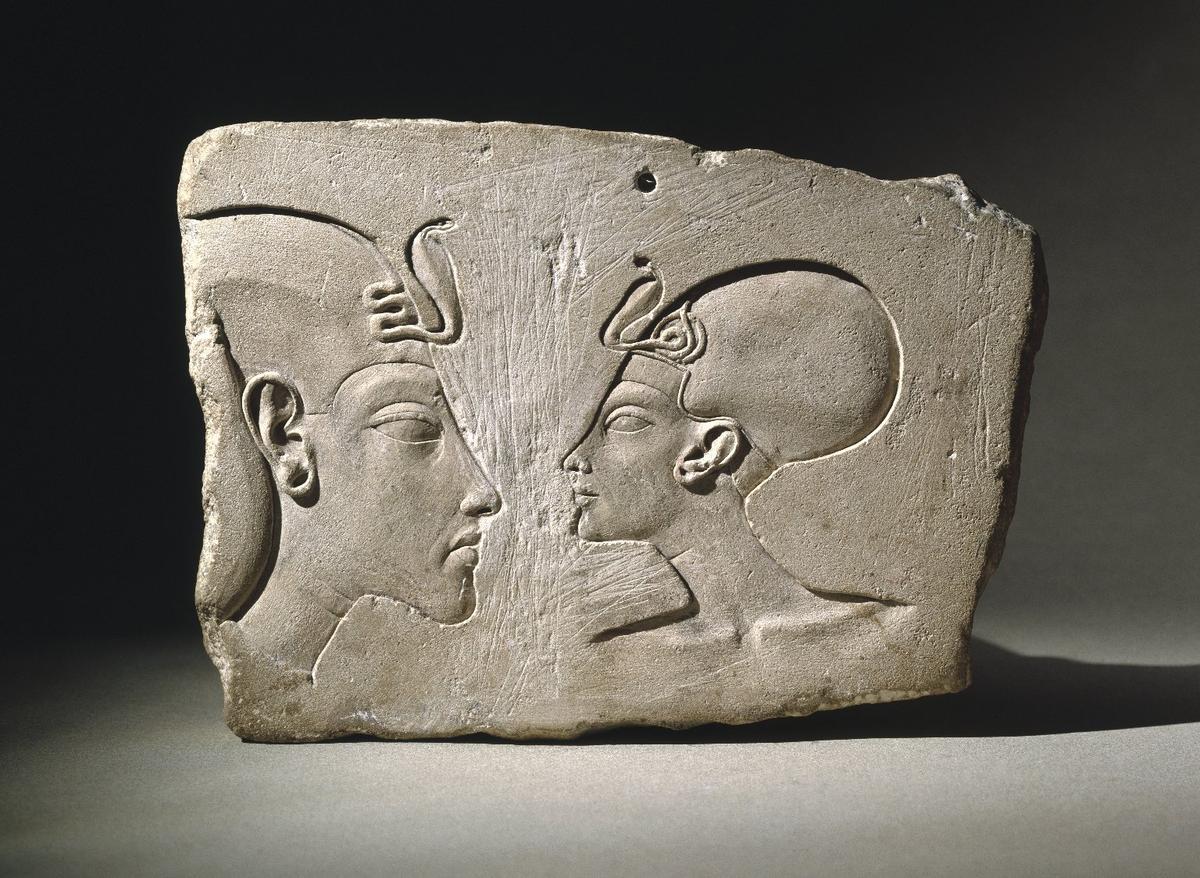

The Wilbour Plaque, ca. 1352–1336 B.C., depicts Akhenaten and Nefertiti late in their reign. (Wikimedia Commons)

The skull of one of ancient Egypt’s most mysterious kings, Akhenaten, is depicted as elongated. This is anomalous, not customary.

The University of Maryland School of Medicine co-sponsored a conference in 2008 specifically aimed at exploring theories about Akhenaten’s physiology.

A university news release from the time sums up some of the questions asked: “Were his artisans following his orders to employ an artistic style for some religious purpose? Or did he really look this bizarre, and if so, why?”

Not only did Akhenaten have an elongated skull, he also had a long neck, long fingers, thick thighs, feminine attributes, and other strange features.

Yale University School of Medicine, Irwin M. Braverman, M.D., said at the conference that the pharaoh may have had two disorders simultaneously. One, craniosynostosis, may explain the elongated skull. There are no records of Egyptians practicing intentional deformation of the skull, yet Akhenaten’s children are also depicted with deformed skulls. With craniosynostosis, fibrous joints of the head fuse at an early age and interfere with skull formation.

Dr. Braverman explained some of the other oddities as resulting from aromatase excess syndrome. This syndrome tips the hormonal balance in favor of estrogen, “leading to the feminization of men, advanced sexual development in girls,” according to the news release. The pharaoh’s daughters are shown with breasts at a very young age, again suggesting the syndrome was passed on genetically.

Prominent Canadian Egyptologist and archaeologist Donald B. Redford, Ph.D., said the pharaoh’s physiology may have more to do with a shift in artistic style after the third year of the king’s reign, when he began worshiping the sun god Aten.

Eastern Europeans Emulated the Huns

The practice of deforming skulls may have been spread through Europe by the Huns. Dominated peoples may have wanted to emulate their conquerors, as skull elongation was often associated with social class.

Researchers at the University of Debrecen and College of Nyiregyhaza in Hungary published a study of elongated skulls from the Carpathian Basin in East-Central Europe in the Journal of Neurosurgery in April outlining this theory.

They said that the Huns had picked up the practice from the Alan-Turkish people, and “Thus the Huns can only be considered to be the transmitters and not the developers of this tradition.”

They wrote: “It seems possible that this custom, which is associated with the finds in the Carpathian Basin, first appeared in the Kalmykia steppe, later in the Crimea, from where it spread to Central and Western Europe by way of the Hun migration. Neither the cranial find described presently nor the special literature on the subject furnish convincing evidence that the cranial deformation resulted in any chronic neurological disorder.”

Follow @TaraMacIsaac on Twitter and visit the Epoch Times Beyond Science page on Facebook to continue exploring the new frontiers of science!