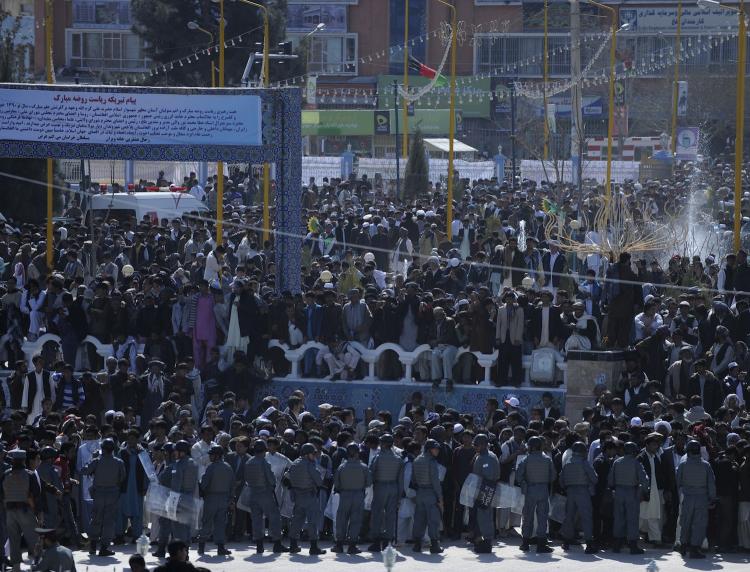

Leading up to the 2014 withdrawal from Afghanistan, U.S. and coalition forces are faced with the challenge of leaving the country in a self-sustained state. This means not only training Afghan security forces to hold their own against al-Qaeda, but also building a stable and recognized government.

This is difficult in a country that was left largely untouched by history. It was left as a buffer zone between Russia and England, when the English were in India. Its isolation was accentuated by the former Afghan monarchy that tried to keep foreigners out of the country.

A fundamental problem in building an Afghan government, however, is its culture of ethnic tribes and warlords. The United States is trying to build a united government in a country whose people are not united, according to Drew Berquist, former U.S. intelligence officer, and author of “The Maverick Experiment.”

“Just like with anything, people are stronger as one. Afghans don’t see the value in that,” Berquist said in an earlier interview with The Epoch Times.

The Afghan people identify themselves with their tribes—the Pashtun, the Uzbek—“and not as Afghans,” Berquist said.

The Afghan government, headed by President Hamid Karzai, has borne a heavy burden as it tries to win the favor of a nation that views it as being part of a foreign occupation.

Berquist believes the pressure on Karzai will be reduced as coalition forces begin their withdrawal process in July, “Because he’s not going to have as many people knocking his door down saying ‘Hey, get this huge military installment down the road and out of here.’”

Success in Afghanistan is divided into three main areas: fighting insurgency, building a mature military and police force, and building a stable government. According to Gen. David Petraeus, commander of U.S. and NATO forces in Afghanistan, the United States is currently on track to fulfill those duties by 2014, according to Department of State (DOS) news service America.gov.

U.S. and NATO forces in Afghanistan focused much of 2011 on pushing the Taliban from the southern part of the country.

The Taliban still poses a threat—particularly against the Afghan government, which it has made a primary target. In addition to trying to expel foreign forces, the Taliban objective is to “overthrow the government and, for some groups, to restore an Islamist regime,” states a report from The International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS).

“Bolstered by a perception among the Afghan population that foreign forces will soon leave, the Taliban’s tactics include assassination and intimidation of officials,” the report states. “They seek to neutralize government institutions, local tribal leaders and religious chiefs, and to introduce their own ’shadow' administration in contested areas.”

Making a scene by attacking high-profile individuals is part of the Taliban scare tactic to make the Afghan people question who will rule the country once coalition forces withdraw. According to IISS, assassinations of Afghan officials increased in 2010.

Prior to the 2010 operations in southern Afghanistan, the Taliban’s intimidation strategy “succeeded in convincing much of the population of southern Afghanistan that the Taliban maintains the capability to carry out its threats and that neither the Afghan government nor the coalition can protect them,” states a report from the Institute for the Study of War.

The Taliban is also leveraging the 2014 troop withdrawal. Among its slogans is, “The West has the clocks ... but the Taliban have the time,” according to a report from retired Four-Star Gen. Barry McCaffrey.

Read more...A Foreign Culture

The battle for perception—part of the U.S. campaign to “win hearts and minds,” and its COIN counterinsurgency strategy—will ultimately determine which governing force the Afghan people recognize.

This campaign has taken a blow from widespread reports of corruption within the Afghan government. “Partly because many Afghans view the central government as ‘predatory,’ many Afghans and international donors have lost faith in Karzai’s leadership,” states a report from the Congressional Research Service (CRS).

Attempts to mend the situation, coupled with its being broadcast to the world, have also crossed cultural lines that have offended the Karzai administration.

“During 2010, Obama administration criticism of the shortcomings of the Karzai government, particularly its corruption, caused substantial frictions in U.S.-Karzai relations,” states the CRS report.

Karzai taking offense points to a larger issue the United States is facing—they don’t fully understand the Afghan culture.

“I haven’t talked to Karzai since January 2008, but the reason is [that] we humiliated him in public” said Jere Van Dyk in an earlier interview with The Epoch Times. He added, in Afghan culture, “honor counts for everything. A man’s pride.”

Van Dyk lived with the mujahedeen in 1980s while they fought the Soviets, and spent 45 days in a Taliban prison in 2008. He recounted the experience in his book, “Captive, My Time As A Prisoner Of The Taliban.”

Van Dyk shares the same perception as Berquist: “Why is the United States having such a hard time? It’s because the Afghans are divided. Deep down they are not committed to this idea of a Western democracy.”

Berquist noted, “We need to help build their nation if it’s going to work, but the original plan was not to go into nation building. The original plan was to go in and rout out the Taliban and Al-Qaeda and weaken them at their home.”

He added, however, that the situation is not as bad as it often sounds. “Especially in intelligence, which is my piece of the pie, we don’t report our successes,” Berquist said. “I think the perception that things are spiraling out of control is false. We have a pretty good footing there.”

This is difficult in a country that was left largely untouched by history. It was left as a buffer zone between Russia and England, when the English were in India. Its isolation was accentuated by the former Afghan monarchy that tried to keep foreigners out of the country.

A fundamental problem in building an Afghan government, however, is its culture of ethnic tribes and warlords. The United States is trying to build a united government in a country whose people are not united, according to Drew Berquist, former U.S. intelligence officer, and author of “The Maverick Experiment.”

“Just like with anything, people are stronger as one. Afghans don’t see the value in that,” Berquist said in an earlier interview with The Epoch Times.

The Afghan people identify themselves with their tribes—the Pashtun, the Uzbek—“and not as Afghans,” Berquist said.

The Afghan government, headed by President Hamid Karzai, has borne a heavy burden as it tries to win the favor of a nation that views it as being part of a foreign occupation.

Berquist believes the pressure on Karzai will be reduced as coalition forces begin their withdrawal process in July, “Because he’s not going to have as many people knocking his door down saying ‘Hey, get this huge military installment down the road and out of here.’”

Success in Afghanistan is divided into three main areas: fighting insurgency, building a mature military and police force, and building a stable government. According to Gen. David Petraeus, commander of U.S. and NATO forces in Afghanistan, the United States is currently on track to fulfill those duties by 2014, according to Department of State (DOS) news service America.gov.

U.S. and NATO forces in Afghanistan focused much of 2011 on pushing the Taliban from the southern part of the country.

The Taliban still poses a threat—particularly against the Afghan government, which it has made a primary target. In addition to trying to expel foreign forces, the Taliban objective is to “overthrow the government and, for some groups, to restore an Islamist regime,” states a report from The International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS).

“Bolstered by a perception among the Afghan population that foreign forces will soon leave, the Taliban’s tactics include assassination and intimidation of officials,” the report states. “They seek to neutralize government institutions, local tribal leaders and religious chiefs, and to introduce their own ’shadow' administration in contested areas.”

Making a scene by attacking high-profile individuals is part of the Taliban scare tactic to make the Afghan people question who will rule the country once coalition forces withdraw. According to IISS, assassinations of Afghan officials increased in 2010.

Prior to the 2010 operations in southern Afghanistan, the Taliban’s intimidation strategy “succeeded in convincing much of the population of southern Afghanistan that the Taliban maintains the capability to carry out its threats and that neither the Afghan government nor the coalition can protect them,” states a report from the Institute for the Study of War.

The Taliban is also leveraging the 2014 troop withdrawal. Among its slogans is, “The West has the clocks ... but the Taliban have the time,” according to a report from retired Four-Star Gen. Barry McCaffrey.

Read more...A Foreign Culture

A Foreign Culture

The battle for perception—part of the U.S. campaign to “win hearts and minds,” and its COIN counterinsurgency strategy—will ultimately determine which governing force the Afghan people recognize.

This campaign has taken a blow from widespread reports of corruption within the Afghan government. “Partly because many Afghans view the central government as ‘predatory,’ many Afghans and international donors have lost faith in Karzai’s leadership,” states a report from the Congressional Research Service (CRS).

Attempts to mend the situation, coupled with its being broadcast to the world, have also crossed cultural lines that have offended the Karzai administration.

“During 2010, Obama administration criticism of the shortcomings of the Karzai government, particularly its corruption, caused substantial frictions in U.S.-Karzai relations,” states the CRS report.

Karzai taking offense points to a larger issue the United States is facing—they don’t fully understand the Afghan culture.

“I haven’t talked to Karzai since January 2008, but the reason is [that] we humiliated him in public” said Jere Van Dyk in an earlier interview with The Epoch Times. He added, in Afghan culture, “honor counts for everything. A man’s pride.”

Van Dyk lived with the mujahedeen in 1980s while they fought the Soviets, and spent 45 days in a Taliban prison in 2008. He recounted the experience in his book, “Captive, My Time As A Prisoner Of The Taliban.”

Van Dyk shares the same perception as Berquist: “Why is the United States having such a hard time? It’s because the Afghans are divided. Deep down they are not committed to this idea of a Western democracy.”

Berquist noted, “We need to help build their nation if it’s going to work, but the original plan was not to go into nation building. The original plan was to go in and rout out the Taliban and Al-Qaeda and weaken them at their home.”

He added, however, that the situation is not as bad as it often sounds. “Especially in intelligence, which is my piece of the pie, we don’t report our successes,” Berquist said. “I think the perception that things are spiraling out of control is false. We have a pretty good footing there.”