With the release of the new film focused on “Number 42,” interest in Jackie Robinson has been revived and rightfully so. He is an important historical figure. And I had the opportunity to do a lot of writing about Jack Roosevelt Robinson in several of my books.

So for your reading pleasure, here is a tasting menu.

One of the perks I have experienced in writing sports books and articles has been the interesting characters I have met, and the friendships I have made.

One such person was Irving Rudd, a Damon Runyan type character who for a time was the publicity director of the old Brooklyn Dodgers.

Irving became a good friend of mine and my wife Myrna. His words enrich my book “Rickey and Robinson.” His words over and over again enriched the five oral histories the Frommers have written.

Jackie Robinson and Irving Rudd had a special relationship. What follows is an insight into the black pioneer from our book “It Happened in the Catskills.” It comes to you in the voice of Rudd.

Recalling a winter weekend in 1954. Rudd and his wife and Jackie Robinson and his wife Rachel went up to the famed Grossinger’s Hotel for some relaxation. Rudd recounts in “It Happened in the Catskills” :

“You skate?” Jackie Robinson asked.

“Not very well.” I answered.

“C’mon, Irv; let’s go skating anyway.”

I said, “Okay,” and we all went to the icehouse. We put skates on. The wives go to the rail to watch. Jackie goes out on the ice and proceeds to lose his balance and falls flat on his back. Geez! The image of Walter O’Malley, the owner of the Dodgers, came into my head. I just blew my job. Jackie Robinson just fractured something—why didn’t I stop him from skating?

Then Robinson gets up and brushes himself off.

“C’mon, Irv, let’s race” He gives me that big smile.

So the two of us like two drunks go around the rink of Grossinger’s. He’s flopping on his knees. I’m sliding on my can. We get up and keep going and flopping and going and flopping and going. And he beats me by five yards.

“Let’s do it again,” he says.

Around we go. This time he beats me by about 20 yards.

“One more time,” he says.

By now, he’s really skating. He is such a natural, gifted athlete. He’s skating like a guy who has been at it for weeks. It’s no contest. He’s almost lapped the field on me.

Now there’s a crowd that’s gathered and they’re cheering. He puts his arms around me, and he wasn’t a demonstrative man. “Irv,” he says, “am I glad you were here this weekend with me. I just had to beat someone before I went home.”

That story gives true insight into Jack Roosevelt Robinson and what he went through in his time as a Brooklyn Dodger. And what a time it was: He played in the major leagues for a decade. He won the inaugural Rookie of the Year Award in 1947, the National League Most Valuable Player Award in 1949, and he helped the Dodgers win six pennants and one world championship. Despite all the pressure he played under, Jackie Robinson was still able to record a lifetime batting average of .311.

From my point of view there is no event in sports history as significant as the breaking of baseball’s color line. It changed the national pastime forever. It ushered in a whole new era in baseball and in all sports. All these long years after Robinson’s death at the age of only 53 in 1972—more athletes, not just the black ones, would be well served to remember the debt owed Jackie Robinson and Branch Rickey.

Here is how I described what it was like at the very start in my book “Rickey and Robinson.”

With the blue number 42 on the back of his Brooklyn Dodger home uniform, Jackie Robinson took his place at first base at Ebbets Field on April 15, 1947. It was 32 years to the day since Jack Johnson had become the first black heavyweight champion of the world.

Many of the 26,633 at that tiny ballpark on that chilly spring day were not even baseball fans, but had come out to see “the one” who would break the sport’s age-old color line. Robinson’s wife, Rachel, was there along with the infant Jackie Jr. Many in the crowd wore “I’m for Jackie” buttons and badges, and screamed each time the black pioneer came to bat or touched the ball.

Jackie Robinson grounded out to short his first time up. He was retired on a fly ball to left field in his second at bat. He grounded into a rally-killing double play in his final at bat of the day.

The Dodgers won the game, 5-3, nipping Johnny Sain and the Boston Braves. For Robinson it was a muted performance, but the first of his 1,382 major league games was in the record books—and he had broken baseball’s color line forever.

“I was nervous on my first day in my first game at Ebbets Field,” Robinson told reporters afterward. “But nothing has bothered me since.”

On April 18, 1947, at the Polo Grounds, in the shadow of the largest black community in the country, Jackie Robinson smashed his first major league home run as the Dodgers defeated the Giants, 10–4.

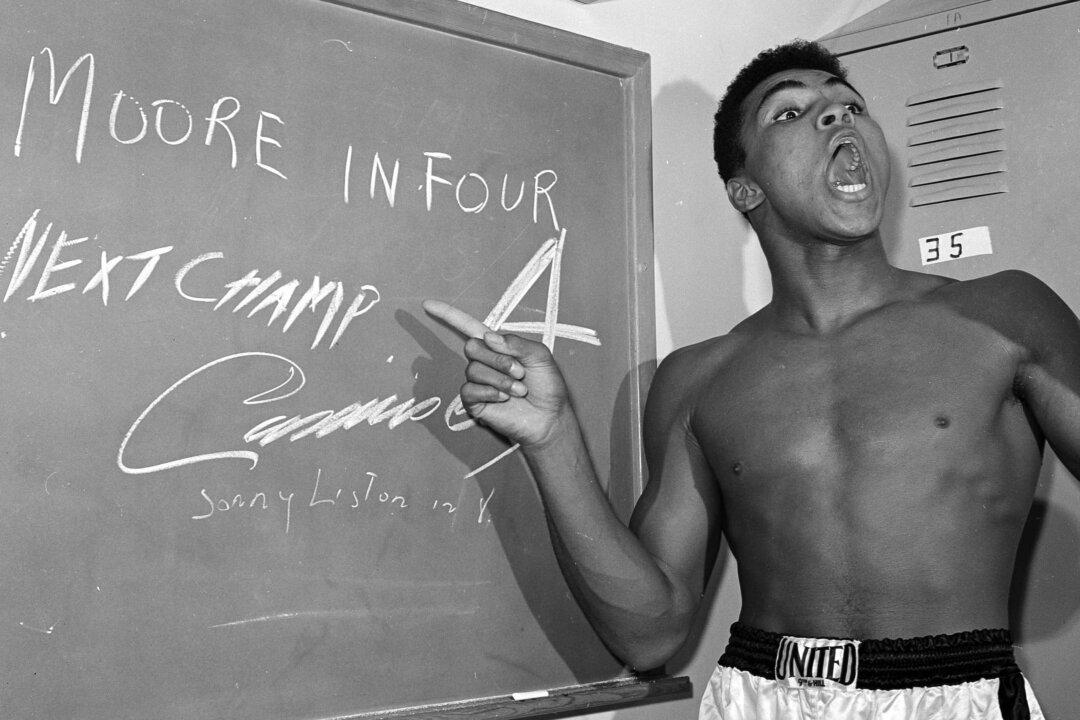

Writer James Baldwin had noted: “Back in the thirties and forties, Joe Louis was the only hero that we ever had. When he won a fight, everybody in Harlem was up in heaven. On that April day the large contingent of blacks in the crowd of nearly 40,000 had another hero to be ‘up in heaven’ about, another hero to stand beside Joe Louis.”

Part sociological phenomenon, part entertainment spectacle, part revolution, part media event, the Jackie Robinson story played out its poignant, dramatic, and historic scenes through that 1947 season.

Toward the end of the season, a Jackie Robinson Day was staged at Ebbets Field. Robinson was now a major drawing card rivaling Bob Feller and Ted Williams in the American League.

“I thank you all.” Robinson said over the microphone in that high-pitched voice. He acknowledged the gifts he’d received, which included a new car, a television and radio set and an electric broiler.

The famed and great dancer Bill “Bojangles” Robinson stood next to Jackie Robinson. “I am 69 years old,” Bill Robinson said. “But I never thought I would live to see the day when I would stand face to face with Ty Cobb in Technicolor.”

The motivations of Brooklyn Dodger general manager Branch Rickey have always been questioned. Why did he sign Jackie Robinson? How much of what he did came from a moral conviction that the color line must go, and how much came from a desire to make money and field a winning team?

Monte Irvin, who wrote the foreword to my book who came up to star for the New York Giants in 1949, suggests that what Rickey did is far more important than why he did it.

“Regardless of the motives,” Irvin observes, “Rickey had the conviction to pursue and to follow through.”

Breaking baseball’s color line enabled Rickey to tap into a gold mine, but he elected not to monopolize the rich lode of talent in the Negro Leagues.

Monte Irvin cold have been a Brooklyn Dodger, as well as other Negro League greats like Larry Doby, Sam Jethroe, and Satchel Paige. But Rickey had Robinson, Roy Campanella, Don Newcombe, and Joe Black. He was very much in favor of the other teams integrating, too.

Bigoted major league club owners who had called Rickey complaining, “You’re gonna kill baseball bringing that n----- in now,” were now asking, “Branch, do you know where I can get a couple of colored boys as good as Jackie and Campy and Newk?”

Branch Rickey invented the baseball farm system when he was with the St. Louis Cardinals and presided over their famous Gashouse gang. He was an incredibly brilliant baseball man. He ran the Dodgers with a calm efficiency. Part of that calm efficiency translated to advising Robinson well. Reacting to the taunts and threats, and fighting back against the bigots could win a battle. But too much protesting could lose the war.

Jackie Robinson took the abuse: the cut signs by players near their throats, the verbal curses, the spiking attempts, the cold shouldering, and the death threats that came in the mail.

By 1949, Jackie Robinson was in his third season as a Brooklyn Dodger and was no longer the lone black man on the baseball diamond—he could now let it all hang out. Branch Rickey who had kept the man Dodger fans called “Robby” under wraps was elated.

“I sat back happily,” Rickey recalled, “knowing that with the restraints removed, Robinson was going to show the National League a thing or two.”

Jackie’s wife Rachel Robinson told me: “It was hard for a man as assertive as Jack to contain his own rage, yet he felt that the end goal was so critical that there was no question that he would do it. And he knew he could do it even better if he could ventilate, express himself, use his own style.”

And what a style it was.

At times the style seemed to be a case of trick photography. He was an illusionist in a baseball uniform, a magician on the base paths. The walking leads, the football-like slides, the change of pace runs all were part of Robinson’s approach to the game.

Today Jackie Robinson remains the stuff of dreams, the striving for potential, the substance of accomplishment. Today he remains a powerful, driving symbol of a person with limitless athletic ability, the weight of his people on his soul, raging against a world he didn’t make.

Jack Roosevelt Robinson played for the Dodgers of Brooklyn for a decade, and then he was done. Not many remember that he was actually traded to the New York Giants in 1956—but he refused to go. The owner of the Giants Horace Stoneham presented Robinson with a blank check –“Fill in the amount…”

Jackie refused. “I came in as a Dodger and that’s how I go out,” he said. “Thanks anyway.”

The thanks is due the man they called “Robby” for what he accomplished in breaking the color line in baseball will last through all eternity. He blazed a path for many to follow, and they have enriched the game of baseball with their talent, verve, drive, and commitment. It has become a better game.

I had the good fortune to interview Jack’s brother Mack Robinson in Pasadena, Calif. I was a bit shocked that he taped me taping him. He was that suspicious of writers. But that is another story.

“From time to time, Mack told me, “I’m watching sporting events and I look at the TV screen and I see Jackie Robinson. I look at the whole spectrum of black America’s life from 1900 to 1947. We’re no longer the butlers, the servants, the maid. We’re senators and congressmen. We’re baseball managers. I trace it back to my brother and Branch Rickey breaking the color line and creating a social revolution in a white man’s world. Blacks have excelled in all areas because Jackie Robinson showed the world we could.”

The last words in my “Rickey and Robinson” also belong to Rudd:

“I always used to think of who I would like going down a dark alley with me. I can think of a lot of great fighters, gangsters I was raised with in Brownsville, strong men like Gil Hodges. But for sheer courage, I would pick Jackie (Robinson). He didn’t back up.”

Finally, a story that appears in “It Happened in Brooklyn,” the oral history I wrote along with my wife Myrna Katz Frommer.

The speaker is identified as Max Wechsler:

When school was out, I sometimes went with my father in his taxi. One summer morning, we were driving in East Flatbush down Snyder Avenue when he pointed out a dark red brick house with a high porch.

“I think Jackie Robinson lives there,” he said. He parked across the street, and we got out of the cab, stood on the sidewalk, and looked at it.

Suddenly the front door opened. A black man in a short-sleeved shirt stepped out. I didn’t believe it. Here we were on a quiet street on a summer morning. No one else was around. This man was not wearing the baggy, ice-cream-white uniform of the Brooklyn Dodgers that accentuated his blackness. He was dressed in regular clothes, coming out of a regular house in a regular Brooklyn neighborhood, a guy like anyone else, going for a newspaper and a bottle of milk.

Then incredibly, he crossed the street and came right toward me. Seeing that unmistakable pigeon-toed walk, the rock of the shoulders and hips I had seen so many times on the baseball field, I had no doubt who it was.

“Hi Jackie, I’m one of your biggest fans,” I said self-consciously. “Do you think the Dodgers are gonna win the pennant this year?”

His handsome face looked sternly down at me. “We’ll try our best,” he said.

“Good luck,” I said.

“Thanks.” He put his big hand out, and I took it. We shook hands, and I felt the strength and firmness of his grip.

I was a nervy kid, but I didn’t ask for an autograph or think to prolong the conversation. I just watched as he walked away down the street.

At last the truth can be told. I am blowing my own cover. That kid, was me.

A noted oral historian and sports journalist, the author of 41 sports books including the classics: “New York City Baseball 1947-1957,” “Shoeless Joe and Ragtime Baseball,” “Remembering Yankee Stadium” and “Remembering Fenway Park,” his book on the first Super Bowl will be published fall 2014.