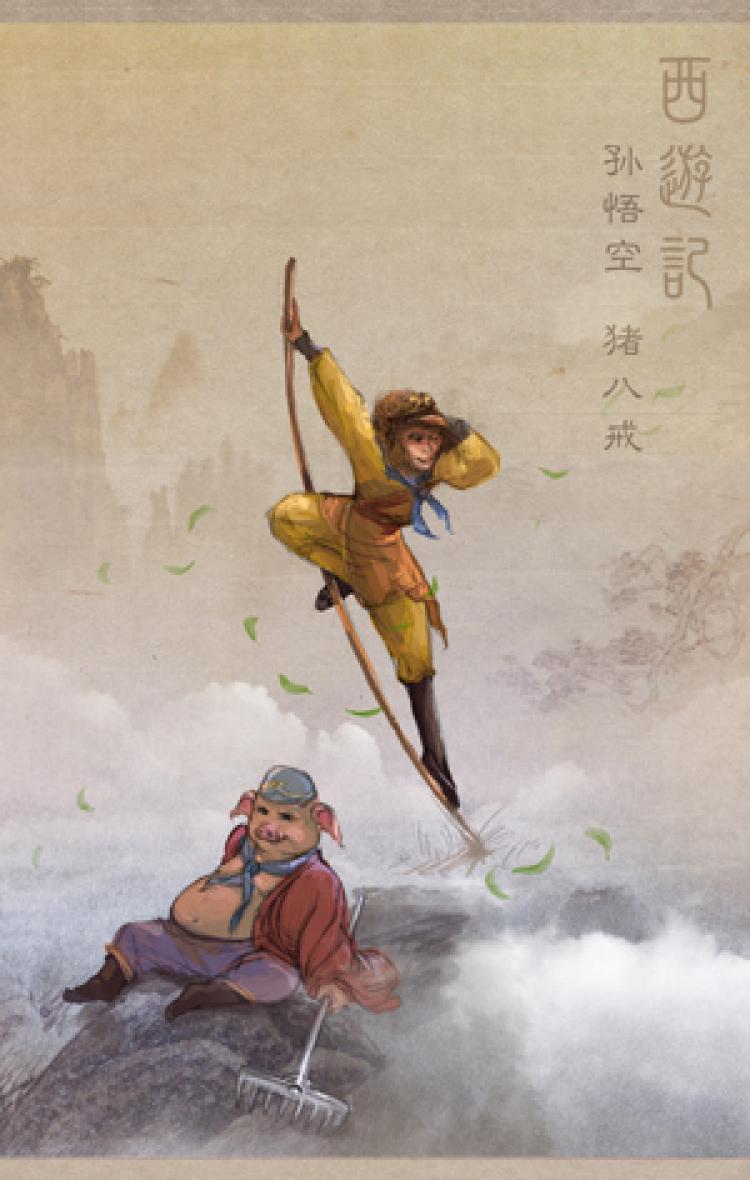

The Story Behind the Scene: ‘Journey to the West’

Journey to the West is one of the Four Great Classical Novels of Chinese literature.

JOURNEYING: Monkey King, a very talented Taoist, and Pigsy, a notorious womanizer, join a Chinese monk for his journey to India in search of sacred scriptures and enlightenment. Vivian Song/The Epoch Times

|Updated: