Two decades ago, a forested mountain ridge in upstate New York was home to nothing but a small cabin and a big dream.

It is now known as Dragon Springs, consisting of a campus and the headquarters of Shen Yun Performing Arts, a classical Chinese dance company that performs for a global audience of more than a million people each year, showcasing a China that existed before communism.

Behind their efforts to forge the elite performing arts company—which has grown to become a cultural force that performs at the world’s most prominent venues—is their belief in Falun Gong.

Mr. Li Hongzhi is the founder of Falun Gong, a spiritual practice that grew so popular in communist-controlled China that the regime has tried to eradicate it since 1999. In response, Falun Gong practitioners have made nonstop efforts in China and abroad to raise awareness about the persecution, including through cultural and religious nonprofits such as Shen Yun.

Mr. Li now designs costumes for Shen Yun, writes lyrics, composes music, and oversees the entire artistic vision of the show, to help revive 5,000 years of traditional Chinese culture that has been all but lost in China. Shen Yun also depicts the present-day brutality of the communist regime.

As the CCP turned against Falun Gong in the late 1990s, Mr. Li was the subject of extensive smear campaigns in China designed to turn the public against him and the popular practice. In the United States, where he and many Falun Gong practitioners found refuge, some of the same tropes the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) used against Mr. Li back then are now appearing in the media.

Driving the narrative is The New York Times, which in recent months has published nine articles attacking Falun Gong and Shen Yun. One of its most recent articles fixated on Shen Yun’s cash reserves of $266 million and implied, without evidence, that it benefits Mr. Li.

Mr. Li said he isn’t involved in Shen Yun’s finances and doesn’t accept compensation for his role as artistic director for Shen Yun.

“No one gives me a cent; I’m unpaid,” Mr. Li said in a rare interview, held at Dragon Springs with Sound of Hope Radio, a Chinese-language nonprofit radio network.

Mr. Li said his focus is on the spiritual elevation of Falun Gong practitioners, including those who have set up companies in the United States as part of their effort to counter the persecution.

The organizations include newspapers such as The Epoch Times, television stations such as NTD News, radio networks such as Sound of Hope, websites, internet blockade circumvention tools, and schools.

While these companies’ founding members are Falun Gong practitioners, Mr. Li says he’s not involved, aside from urging practitioners to elevate their character through spiritual practice.

“Their operations, staffing, and finances aren’t something I intervene in, so I don’t really know about how they are run,” he said.

“I must allow them to walk their own path; that’s part of their spiritual journey. If I keep intervening, it’s like tearing down the bridges and roads along their path. So, I don’t manage any of those things—my focus is solely on the practitioners’ spiritual practice.”

Mr. Li takes pride in the spirit of frugality. This virtue has taken Shen Yun far since the hardscrabble years and seen the company grow into a global influence. Less visible is the long list of bills they have to pay from day to day: talent to train, expensive production equipment to acquire, new costumes to make each year, and salaries to pay.

These high costs are one of the reasons Shen Yun keeps cash reserves, the company’s president, Zhou Yu, said.

The COVID-19 pandemic taught them to be financially prepared in case of any emergency; they managed to stay afloat through the pandemic, and keep all their staff, despite not performing for 1 1/2 years. The company has affirmed it has “every intention” to do the same if need be in the future.

The funds also serve another significant purpose: “to prepare for the time when Shen Yun can go to China when change occurs in the country,” Zhou said. “We are currently preparing for performances in China by cultivating talent and reserving funds.”

Communist China is still hostile to Shen Yun. It is, however, the company’s dream to take China’s 5,000 years of traditional culture back to its homeland.

The Beginnings

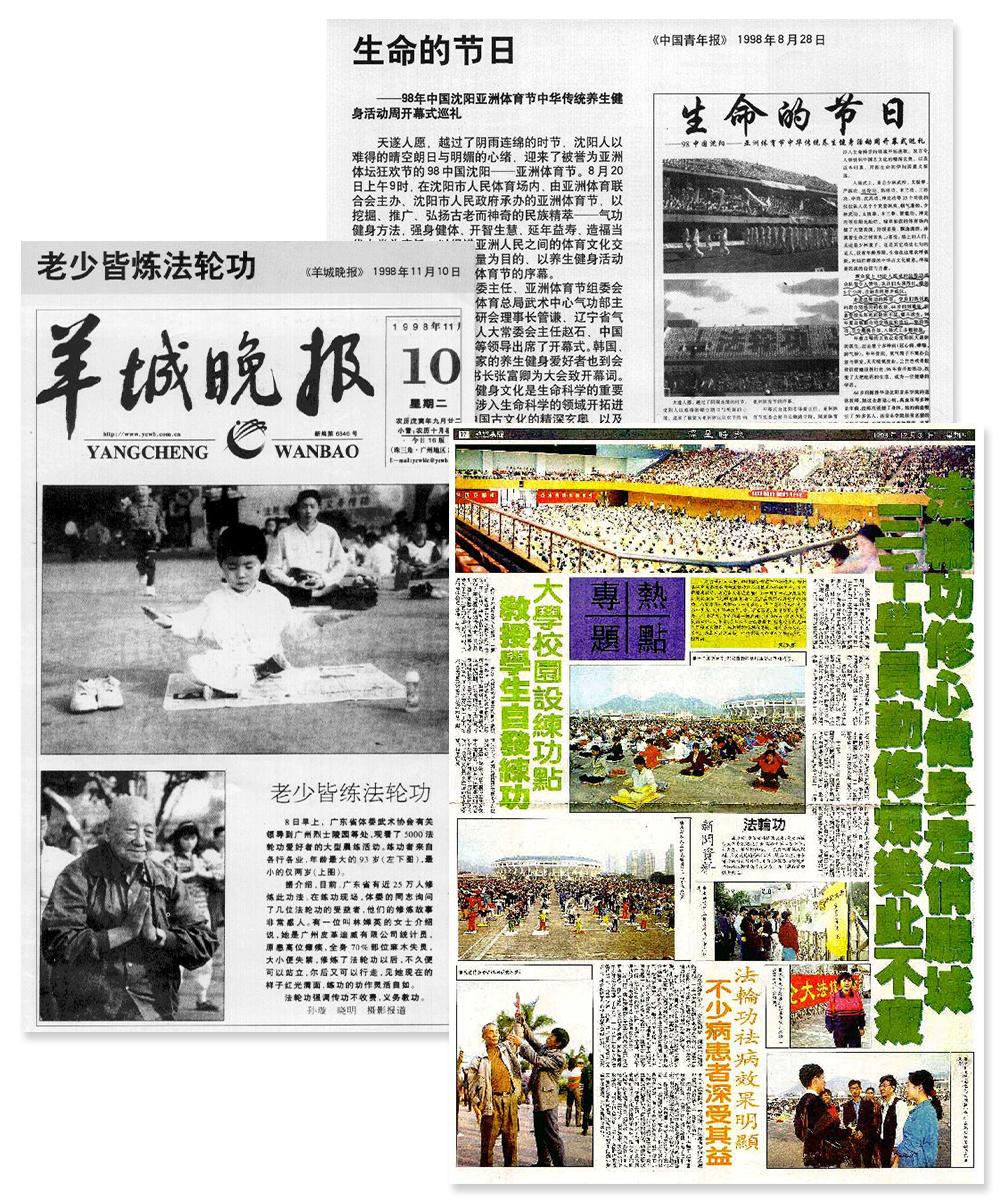

When Mr. Li brought Falun Gong to the public in 1992, China was going through a major shift. The Party’s atheist communist ideals and series of deadly political campaigns—from the decade-long Cultural Revolution to the Tiananmen Square massacre—had shaken the Chinese people to the core.Qigong, an ancient energy system that integrates body postures and mindfulness, rose to fill the spiritual hole in a population that for thousands of years had based their beliefs on Buddhism, Daoism, and Confucianism.

In one 1992 seminar in the northeastern Chinese city of Changchun, 40-year-old Mr. Li awed the crowd by explaining spiritual concepts in layman terms that had long confounded even ardent qigong enthusiasts. Soon, they were renting venues for him, eager to hear him talk in greater depth and in a more formal setting.

In the two years that followed, Mr. Li delivered 56 seminars that averaged nine days each, across the nation. An estimated 60,000 people attended. Those attendees passed on the practice to friends and family; the friends and family passed it along further; and it rapidly spread all over the country, person-to-person.

Truthfulness, compassion, and tolerance are the guiding principles of Falun Gong, which also encompasses a set of meditative exercises. Practitioners are taught to apply these simple concepts in all aspects of their lives to improve their character. This is described as their personal cultivation.

In 1994, Jin Chengquan attended one of the last lecture series in his home province of Jilin.

Then 20, Jin remembered being struck by Mr. Li saying that “matter and mind are one and the same.” It made sense to him then that improving one’s inner self could bring about physical benefits.

‘Your Influence in China Is Too Great’

Unassuming, punctual, patient: These are the words several early lecture attendees used in describing Mr. Li to The Epoch Times.Traveling across China to deliver his lectures wasn’t a life of luxury. Longtime volunteer assistant Mi Ruijing recalled noticing signs of wear on Mr. Li’s clothes and shoes, and Ye Hao, a retired senior Chinese police official who traveled with Mr. Li, said Mr. Li hand-washed his clothes and hung them up to dry each night.

He said their meals on those trips were often ramen topped with the cheapest type of sausage.

The lectures often sold out quickly, and stadiums sometimes opened up additional space to accommodate the capacity.

Notwithstanding the acclaim, Mr. Li charged a low entry fee of a few dozen yuan, less than $10 for new students, and half price for repeat attendees, barely enough to cover costs. The emphasis wasn’t on making money but on teaching how to hone one’s character. Attendees took it to heart, and the culture within the lectures transformed rapidly. After the first day, many stopped vying for front-row seats. People gave up tickets or ceded the best spots to first-timers and returned lost jewelry or wallets to staffers, who used a loudspeaker to find the owners.

The lecture series was ultimately transcribed and made into a book, which became the main text of Falun Gong, called “Zhuan Falun,” or “Turning the Law Wheel.” The book made the best-seller list in Beijing multiple times. The Chinese Embassy in France invited Mr. Li to Paris in 1995 for his first overseas lecture. And Chinese state media publicized the healing effects of Falun Gong and how practitioners had uplifted society.

Official estimates put the number of Falun Gong practitioners in China at between 70 million and 100 million in the late 1990s.

Top CCP officials were taking notice of the burgeoning popularity with unease.

In 1996, a department director in the State Council invited Mr. Li to dine with her.

“At that time, I was often invited out to eat by people who were hoping to be healed,” Mr. Li said in the interview.

“After we sat down, the official was straightforward with me, saying, ‘Teacher Li, your influence in China has become too great. You need to leave the country.’”

Knowing the CCP’s history well, Mr. Li understood the implied threat and saw no other choice if he wanted to keep practitioners safe under a ruthless atheist regime. He applied for a priority visa on account of extraordinary ability and in 1998 emigrated to the United States.

At the same time, Chinese spies were after Mr. Li in the United States. He spent roughly a year on the road moving constantly so they wouldn’t be able to find him.

Eventually, some Falun Gong practitioners bought and donated a patch of land in upstate New York. There, a group of volunteers painstakingly built Dragon Springs, a complex designed in the architectural style of China’s ancient Tang Dynasty, and the headquarters of Shen Yun.

Gradually, the community grew and became a haven for people fleeing the brutality in communist China. Children who had lost their parents to torture in China became some of Shen Yun’s earliest performers.

“We Falun Gong practitioners are essentially refugees in the United States,” Zhou said. While other arts groups may rely heavily on corporate donations or government funding, Shen Yun has had to be self-reliant.

“Major American companies, fearing the CCP, have also refrained from sponsoring us. We are surviving the challenges through our own efforts,” Zhou said.

Despite the ongoing attacks and suppression, Shen Yun says it remains committed to its mission: “to showcase the beauty, majesty, and spirituality of China’s 5,000-year-old civilization.”

Shen Yun plays a role in the effort to “give voice to victims’ stories” and save lives, the company said in a statement.

“We cherish this country, and are grateful for the liberty it provides.”