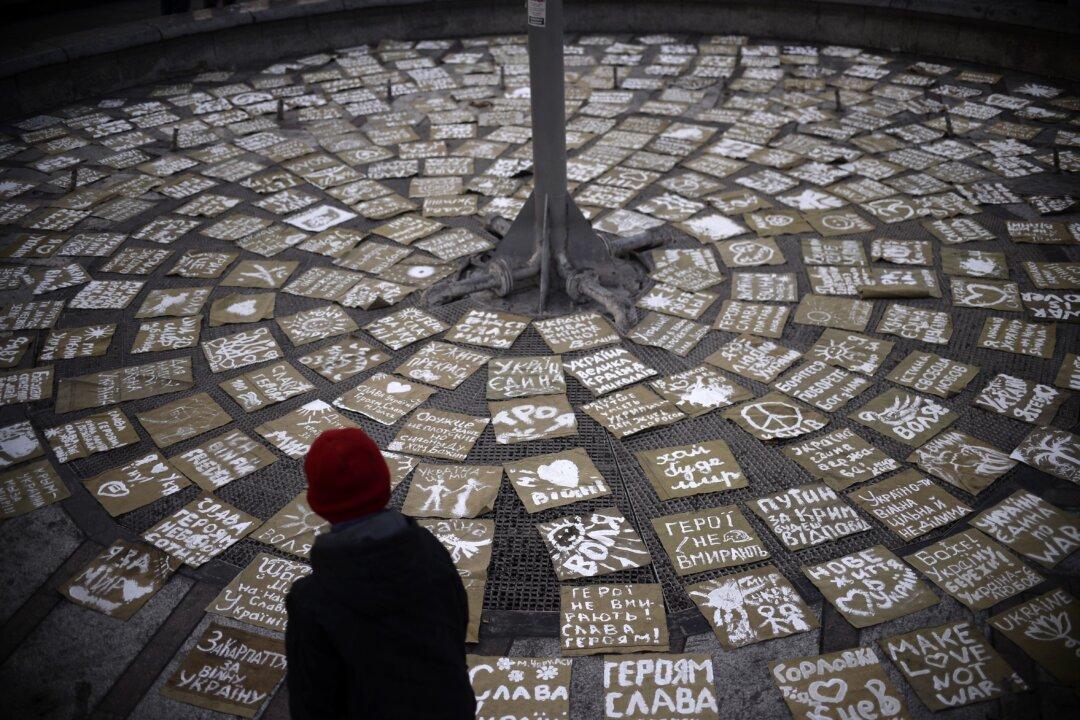

Maidan Square in Kiev. Taksim Square in Istanbul. Tahrir Square in Cairo. Recent democratic movements around the globe have risen, or crashed and burned, on the hard pavement of vast urban public squares. The media largely has focused on the role of social media technology in these movements. But too few observers have considered the significance of the empty public spaces themselves.

Comedian Jon Stewart was one who got it. He quipped that if he ever becomes a dictator, he’d “get rid of these [bleep]ing squares” Why? Because “nothing good happens for dictators” in such places.

In the U.S., children are taught that the public square is essential to democracy. Here, the phrase “public square” is practically synonymous with free political speech. But these days “public square” is more likely to be a metaphor for media in all its forms than it is a reference to an actual, concrete place.

For at least a generation, urban planners and sociologists have bemoaned the decline of public space in American life. While older towns and cities, particularly in the Northeast and South, may have been built around a commons or town square, most newer cities in the West—often planned with the automobile in mind—were designed without town centers. The explicit intention of many planners was to give people their own private spaces rather than provide opportunities to come together in public.

“We stopped building public squares in the post-war years also in part because of the fear of who would use them,” says Fred Kent, president of the Project for Public Spaces in New York. “And those we do have, we don’t use very much.”

If public squares are essential to democracy, is their relative absence in modern American life bad for our democracy—or a sign that we’re not as democratic as we imagine?

I can’t help but think of that over-the-top Cadillac television commercial that features a tightly wound, barrel-chested, blond dude who exalts the “crazy, driven” American work ethic while disdaining those “other countries” whose people “stroll home,” “stop by the café,” and “take August off.” The commercial, while clearly a caricature, does manage to capture a macho disdain that Americans—including myself—are sometimes guilty of exhibiting toward non-productive time, the hours and days that are not filled with goal-oriented activity.

That bias toward filling time also applies to our collective approach to space. Think of the hyper-commercialized, sensory overload that is New York’s Times Square or the clutter of billboards that line L.A’s Sunset Strip. Whether it’s a shopping mall or a new park, planners harbor a strong bias toward filling spaces with everything from vendor stalls to matching outdoor furniture. Places, they tell us, can’t just lie there empty; they must be “activated” by amenities and organized programs.

It’s tempting to pin this desire for distraction on our aggressive consumer culture or on an ingrained American emphasis on action over repose. But the causes are likely even more far reaching. Herbert Muschamp, the late architecture critic for The New York Times, felt that “horror vacui”—the fear of emptiness—kept Americans from creating and enjoying open public spaces. But empty spaces, he argued, are the kind of places—think Japanese gardens—that encourage us to collect our thoughts and ponder new ones.

Common public places are also ideal—maybe even necessary—for the performance of quintessential democratic behaviors. As in Maidan, Taksim, and Tahrir squares, they’re a stage for the expression of political opinions. But they’re also a space that facilitates the everyday social interaction of citizens whose paths may otherwise never cross.

In capital cities, such spaces are where groups of citizens can make political claims and demonstrate the scale of their displeasure within close proximity of governmental power. But everywhere else, diverse and open public places that are not the domain of any particular social group or stratum are the physical embodiment and symbolic expressions of a diverse citizenry peacefully inhabiting a common geographic place. They connect us to democracy not through an interaction with the government but by encouraging us to interact with one another.

In Washington, protests are increasingly scripted and controlled by organized interest groups rather arising organically out of broad public sentiment. Nationally, the decline of public space is part of a troublesome broader trend of Americans choosing to socialize with and live near people very much like themselves. It follows, then, that a fragmenting country whose constituent parts are increasingly keeping to themselves would abandon the public square, both figuratively and literally.

So, yes, the decline of public space in America is bad for democratic culture. Balancing the parts and the whole has always been the most challenging aspect of the American experiment. And if we want our democracy to function and thrive, we need to learn to live with and negotiate social differences and competing interests.

It won’t solve all our democracy’s problems, but restoring spaces where Americans can interact across ideological, religious, racial, and class lines would be a promising start.