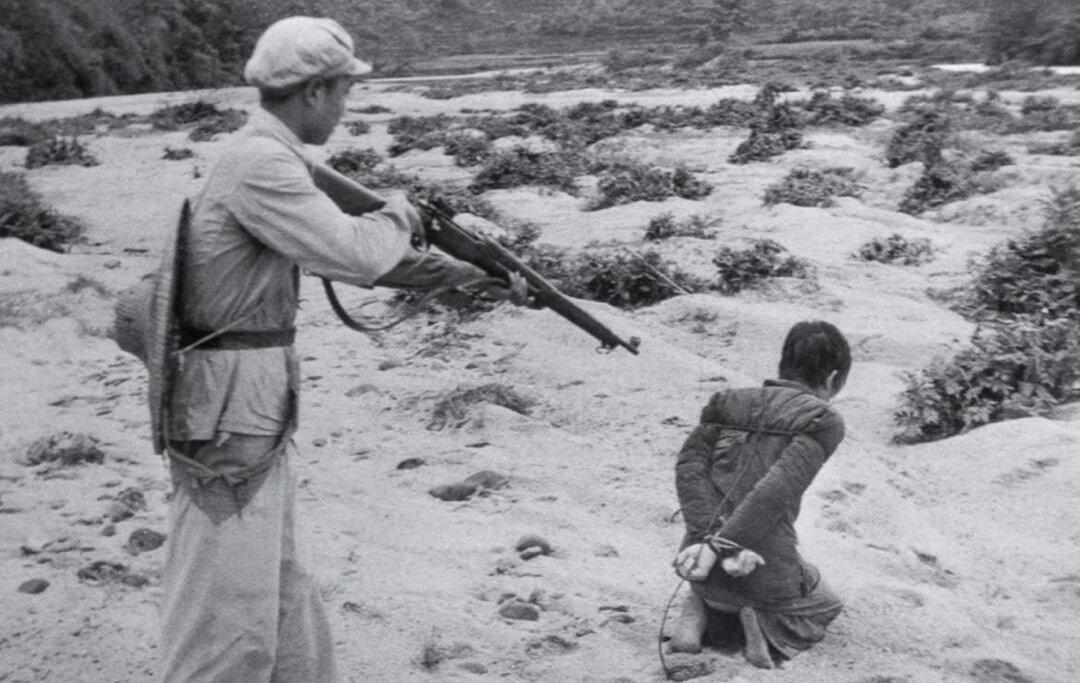

Like a funnel cloud longing to touch Earth and become a tornado, the specter of Communism was up in the air, with no Earthly home, haunting Europe in early 1871.

The Paris Commune, a bloody insurrection covering 73 days, became Communism’s first Earthly home, like a tornado touching down. The specter was embodied.