During the late 11th century, an order of Nizari Ismailies was formed in Persia and Syria by a man called Hassan-i Sabbah. These were the notorious Hashshashins who captured many mountain fortresses and posed a threat to Sunni Seljuk authority in Persia. Perhaps the Hashshashin were most famous for the way they got rid of their opponents – through highly-skilled assassinations. In fact, the word ‘assassin’ is said to have originated from this order.

Although there are many stories about the Hashshashin, it is rather difficult to separate fact from fiction. For a start, much of our accounts about the Hashshashin are derived either from European sources or people who were hostile towards this order. For example, according to a story heard in the orient by the Italian traveller, Marco Polo, Hassan would drug his followers with hashish, and lead them to ‘paradise’. When his followers regained their senses, Hassan would claim that he was the only one who had the means to allow them to return to ‘paradise’. Thus, his followers were completely devoted to Hassan and carry out his every will. Nevertheless, there are some problems with this story.

For instance, the use of hashish might have been a false tale. It seems that the term hashshishi was first used by the Fatimid caliph al-Amir in 1122 as a derogatory reference to the Syrian Nizaris. Instead of literally meaning that these people took the hashish drug, it was supposed to be taken figuratively, and meant ‘outcasts’ or ‘rabble’. This term was applied by anti-Ismaili historians to the Syrian and Persian Ismailies, and eventually spread through Europe via the crusaders.

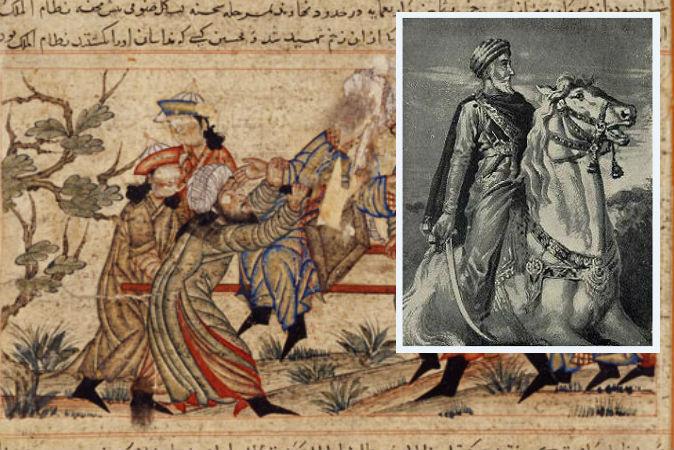

Even the Hashshashin’s reputation as cold-blooded killers may be questioned. There were indeed figures who were murdered by the Hashashins in broad daylight. Perhaps one of their most famous victims is Conrad of Montferrat, the de facto King of Jerusalem at the end of the 12th century. According to history, Conrad was murdered while strolling in the courtyard of the city of Tyre with an entourage of mailed knights. Two hashshashins, disguised as Christian monks, walked towards the centre of the courtyard, stabbed Conrad twice, and killed him. Whilst it is unknown who hired these hashshashins, it has been commonly claimed that Richard the Lionheart and Henry of Champagne were responsible.

What is more impressive than the boldness of the hashshashins is perhaps their efficient use of ‘psychological warfare’. By instilling fear into their enemy, they managed to gain their enemy’s submission without risking their own lives. The great Muslim leader, Saladin, for instance, survived two hashshashin attempts on his life. Nevertheless, this placed him in a state of fear and paranoia, for fear of more assassination attempts. According to one story, one night during his conquest of Masyaf, in Syria, Saladin woke up to find a figure leaving his tent. Beside his bed were hot scones in the shape characteristic to the hashshashin, along with a note pinned by a poisoned dagger. According to the note, he would be killed if he did not withdraw. Needless to say, Saladin decided to settle a truce with the hashshashins.

Despite the hashshashins’ notoriety and skills, they were wiped out by the Mongols who were invading Khwarizm. In 1256, the hashashshin’s stronghold, once thought to be impregnable, fell to the Mongols. Although the hashshashins succeeded in recapturing and holding Alamit for several months in 1275, they were ultimately crushed. From a historian’s perspective, the Mongol conquest of Alamut is a highly significant event, due to the fact that sources which would have been able to tell the story from the hashshashin’s point of view were completely destroyed. As a result, we are left with a somewhat romanticised view of this order, perhaps best seen in video games, most famously in the Assassin’s Creed series.

Republished with permission from Ancient Origins. Read the original.