Janet Kern is on the brink of completing her Nez Perce film, “Horse Tribe.” Due to financial struggles, the film has been in the making for 10 years. But this inconvenience may have turned into a boon.

“If I hadn’t stayed with the story and concluded it at a different time...” said Kern, a documentary journalist.

She would have missed “the choices the players made, which illuminates human nature in a way that is complex, full of nuance, struggle, and humane— more than a story of simple success.”

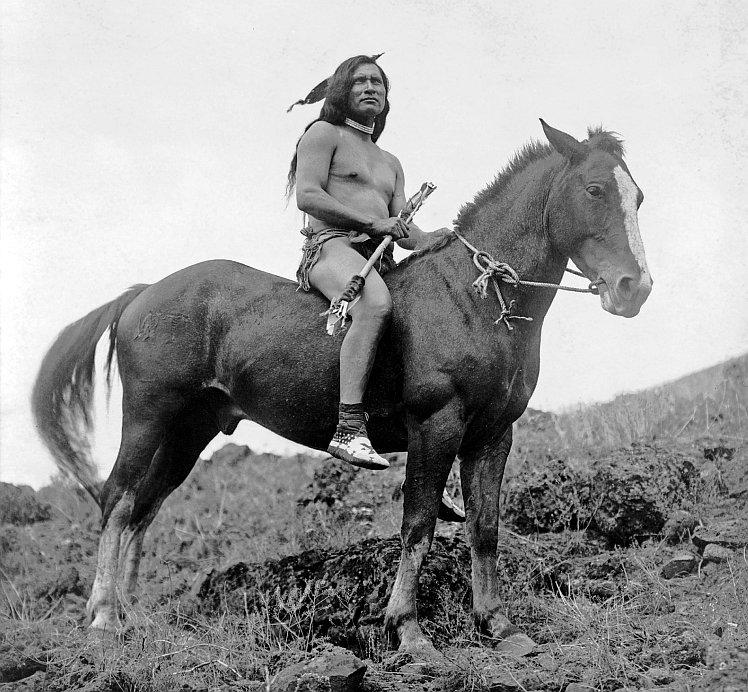

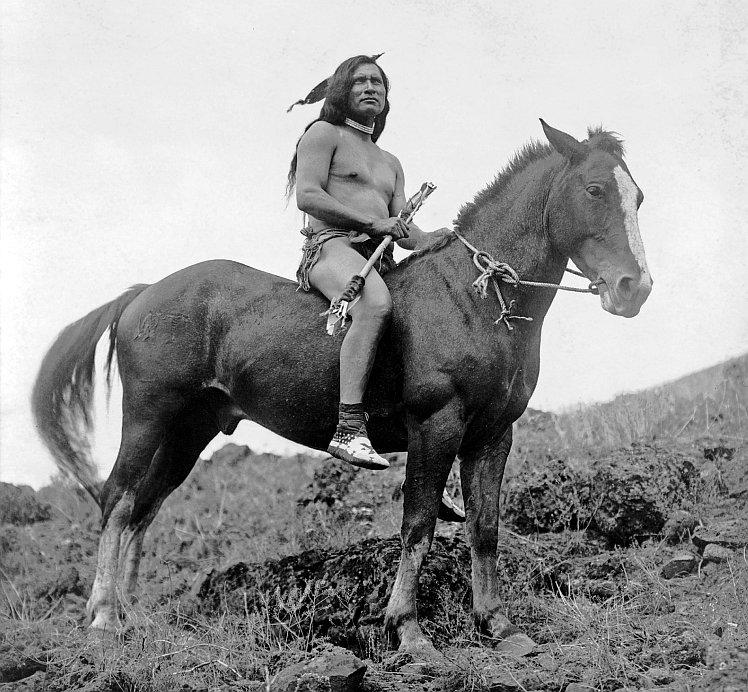

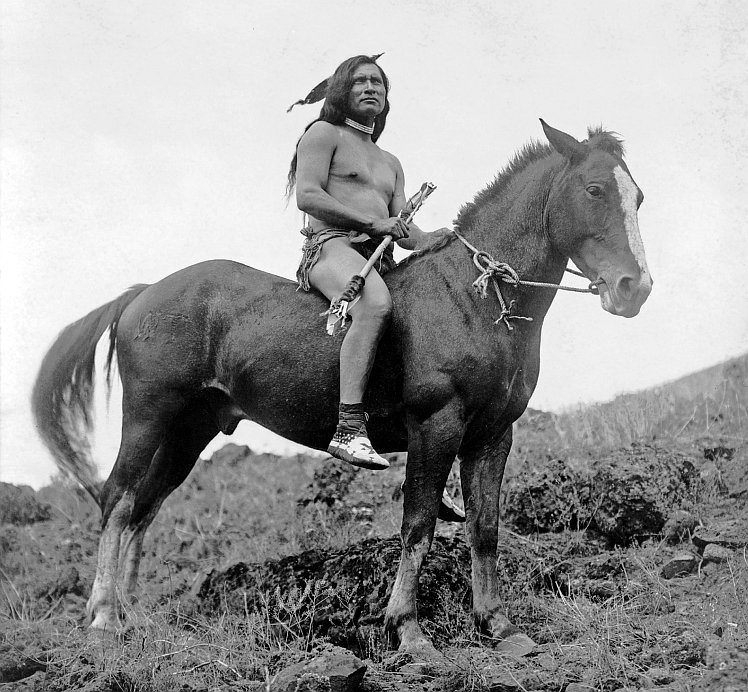

The film is based on the process of the modern Nez Perce tribe getting back their horses, a cultural core, after losing everything during a war with the U.S.

The only Nez Perce reservation is in Lapwai, Idaho, of the Pacific North West. They have been recognized for centuries as one of America’s greatest horse tribes.

Gen. W.T. Sherman, a Civil War general, called the epic battle “the most extraordinary of Indian wars.” In 1877, the U.S. Army chased the Nez Perce for 1,300 miles, losing every battle except the last.

According to Kern, the Nez Perce’s initial success and victories were due to their “superior knowledge of horses and how to travel with them.” But after losing the last skirmish, the government took away their most valuable weapon, their horses.

The “epic story boils down to a heroic, but deeply flawed main character,”—Rudy Shebala, a Navajo who married a Nez Perce and crossbred a new breed of horses, “The Nez Perce horse.”

This marked the return of horses for the tribe.

“In the long run if we had the horse culture back, it would do so many good things for our people. [That culture] is associated with hard work and ethics that would prompt the revitalization of our culture entirely,” said Aaron Miles, the natural resource manager of the Nez Perce tribe.

According to Kern, the Nez Perce has always had a “romantic affiliation” with the Appaloosa, most commonly known as the spotted horse. Shebala crossbred the Appaloosa with a rare breed called the Akhal-Teke—only 2,000 exist in the world. The crossbreed created a more narrow kind of horse, easier to ride and grip.

As a part of breeding horses, Shebala also created the Nez Perce Horse Registry, a systematic way to register horses and keep track of which horses are owned, along with how they are bred.

Shebala is “charismatic, sometimes temperamental, and a brilliant horseman,” Kern said.

He convinced a Minnesotan man to move his four rare stallions to Idaho for the Nez Perce’s breeding use. Shebala was also “spearheaded” in getting the Administration for Native Americans (ANA) to raise $2.3 million to fund the Nez Perce horse registry, over the course of the nine years that he was in charge.

“He was very much the driving force behind the energy and success of the horse program. But he succumbed to his personal demons and got a DUI,” said Kern. Shebala was then dismissed by the tribal council from his position as director of the Nez Perce horse registry.

It was a controversial dismissal. Some felt that a Navajo should not have been running the Horse Registry, while others felt he was vital to the success of the Registry.

“It was difficult to keep the program going [after Shebala left]. It continues operation on a modified scale,” Kern said.

It costs $300,000 a year to transport, feed, water, inoculate, and fence the horses. Without Shebala’s help, the “herd was getting unmanageable once the last of their grant had expired,” Kern said.

At its peak, the Registry had 130 horses. The tribal council voted to put some 40 horses off to auction, stirring strong feelings. In the end, only 25 were auctioned when rebels took away the rest from the pre-auction site, setting them loose on remote tribal forestland. “It was a very interesting political development,” Kern said.

“Some tribal members thought the [auctioneers] were crooks that should be prosecuted. Others thought they were modern warriors who needed to do what they had to do,” she said.

Kern, a white Scottish woman, sat among a circle of 300 tribe members of the Joseph Band, a Nez Perce group at the Colville Reservation in Spokane, Wash. Laughter broke throughout the room as Janet realized that “walk in backwards,” meant to enter in reverse order, not literally walk backwards. Janet had entered and walked backwards to her seat as the tribe silently watched, fighting to swallow their giggles.

What stuck out to Janet about the tribe was their “reverence and wonderful sense of humor. No one enjoys a joke more than they do,” despite their sorrowful history, she said. “I don’t know how they remain intact after such widespread loss.”

A Legacy Recorded

Footage of interviews with tribal elders is going to be donated to the Nez Perce museum in Idaho. These interviews include tribal elders telling stories of growing up and fate.

“I don’t know if those stories exist except in the memories of those they shared it with,” Kern said. “Now that material will be available for their descendants and other tribal members to have access to 100 years after they’re gone. ... It may matter a lot someday.”

Kern feels that her film will be greeted with ambivalent feelings. “It’s a realistic portrait of what happened at a given point in time. Peoples’ actions are not always noble, positive, or well thought out.”

“It’s a 21st century story about an ancient culture,” she said.

Kern hopes the broadcast of the film will draw attention and support for the Nez Perce registry.