How does our educational system prepare the next generation of students for living and working in the digital age? Try giving out free pizza.

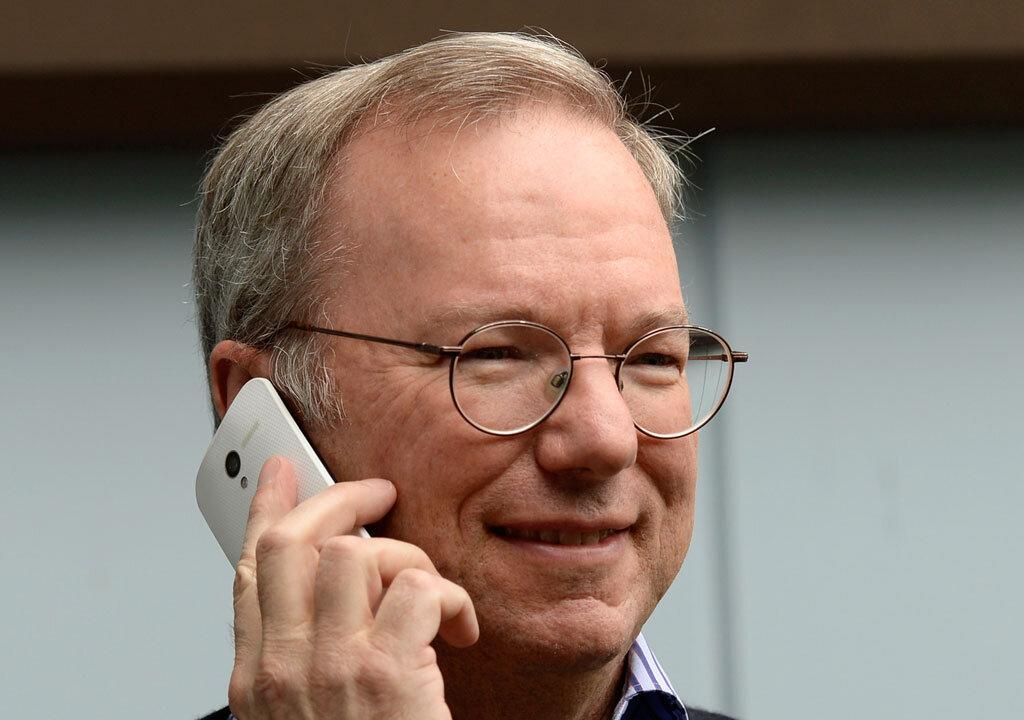

Learning to use analytical skills to measure and solve problems is an essential life skill in the coming era, one that every major university should be — but isn’t necessarily — teaching students, said Eric Schmidt, Google’s longtime CEO, and now its executive chairman. All that would be needed to jumpstart that process is to gather smart young people interested in entrepreneurship in a room together for pizza and get them talking to each other.

“Because that’s how people learn,” he said. “The sense of being in the middle of something great is hugely motivating to people who want to start new things.”

In order to create another “hive of knowledge” like Silicon Valley, cities need to reproduce key elements that seem to make everything work, like a stable base of venture capital, weak employment contract laws, a culture of sharing, and a steady supply of very smart people flowing in and out, said Schmidt. But it’s a tall order.

“Here in Cambridge, we have some of the smartest people in the world … If I can be critical for a sec: Why have you guys not produced the equivalent of Twitter, Facebook, Google, and so forth? I don’t know,” he said. “So there’s an action item for you.” His comments reflected the corporate reality, though the key founders of both Microsoft and Facebook were former Harvard College students.

Schmidt’s remarks came Thursday evening during a wide-ranging talk about leadership, innovation, and entrepreneurship at the Harvard Kennedy School (HKS), a session sponsored by the Institute of Politics with moderator David Gergen, co-director of the Center for Public Leadership, and an introduction by HKS Dean David Ellwood.

Schmidt defined entrepreneurs as confident, often young visionaries able to see what others cannot and who neither suffer fools gladly nor want for self-confidence.

“We need to celebrate these people, we need to find them, and if you’re not like that, you need to befriend them because you’re going to work for them, so be nice to them,” he told students. He said they also don’t wilt in the face of adversity.

“The successful entrepreneur doubles down, fights harder, leads harder, challenges harder, and eventually wins. The unsuccessful entrepreneur gets scared, gets tentative, loses confidence, falls apart,” Schmidt said. “That’s the difference between $1 billion and zero.”

Saying he was a C-level executive at Novell and Sun Microsystems before joining Google in 2001, Schmidt said the key to leadership, besides a sense of humor, a taste for risk, and a tolerance of failure, is to surround yourself with bright people and let them create.

“I think it’s important that you recognize that you’re not actually doing the work that other people are, that your job is to understand what they’re doing, to get the strategy right and empower them. Most of the problems that companies get into … is the failure of strategy,” he said, adding, “The job of a leader is to call back and say: What are we going to do about this and keep people’s noses to fixing it.”

Schmidt challenged HKS students to solve the nation’s employment problem as a pathway to relieving a host of other societal ills, such as crime and health, and he urged those studying foreign policy to apply mathematical laws used frequently in the digital world to identify and reconsider the connection and relationships within a handful of centers around the world.

Taking to task what he termed the inefficiencies of most nonprofits and NGOs, Schmidt called for more innovation.

“The thing I would tell you about nonprofits is that they’re full of extremely well-meaning people who need to build things,” he said, referring to online platforms that can deliver services. “There’s so much waste in the philanthropic world because they don’t measure their outcomes. We’ve asked them the basic questions. How many of this did you save? How much of this? And they can’t answer them. That’s an indication of poor management in need of better tools.”

This article was originally published at the Harvard Gazette.