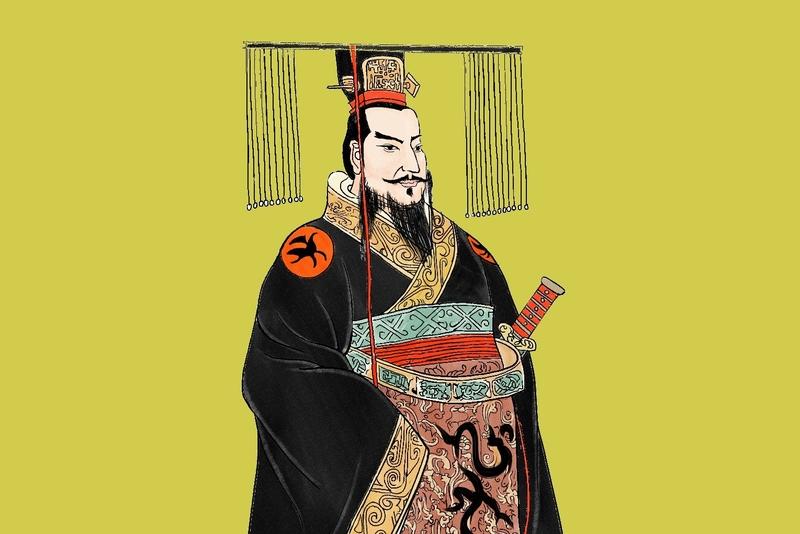

This is the ninth in a series of articles by Epoch Times staff describing the foundations of Chinese civilization, and setting forth the traditional Chinese worldview. The series surveys the course of Chinese history, showing how key figures aided in the creation of China’s divinely inspired culture. This installment introduces Qin Shi Huang, the first historical emperor.

Ending the tradition of abdication to a chosen successor, as had been the case with the rulers Yao and Shun, Yu the Great founded the hereditary Xia Dynasty. A thousand years passed before King Wu defeated the Yin Shang kingdom, which had subdued the Xia, and founded the 800-year-long Zhou Dynasty.

During the Zhou kingdom’s gradual decline from the Spring and Autumn Period beginning in the eighth century B.C., the fractured Chinese civilization entered a centuries-long saga of political intrigue, military exploits, and cultural maturation.

The Warring States and the Rise of Qin

The final victory of Qin State and its king Ying Zheng, who went on to rule China’s first imperial dynasty, was the conclusion of a historical saga that played out over centuries in what the Chinese referred to as “tianxia,” the known world under heaven.

The rise and fall of Chinese dynasties can be characterized by its cyclical pattern: As society sinks into moral degeneracy, social disorder, and natural disaster, rebellious forces emerge to purge the corrupt or ossified regime and establish a new dynasty.

According to ancient records, China was once home to thousands of states. By the time of the late Zhou Dynasty, there were hundreds, and this figure declined yet further to about 140 in the Spring and Autumn Period. Come the era of the Warring States in the final years of the Zhou, only seven remained standing. Their rulers now fancied themselves kings in their own right, ignoring the feeble decrees of the powerless Zhou monarch.

Ying Zheng was the latest of six ambitious kings governing the western Chinese state of Qin, who spent over a century turning this backwater region into a regional power by inviting and employing talented administrators and advisers from all around China. Many of these men had been overlooked in their homelands, but Qin’s rulers readily accepted them into the highest government offices, greatly strengthening the state.

The Warring States Period began roughly in 500 B.C. and lasted for about 300 years. As Qin grew, its primary rival was the wealthy Qi State, a coastal power in eastern China.

To negate Qi’s initial edge, Qin State embarked on a patient and intricate game of diplomacy whereby it encouraged contradictory schools of inter-regional relations. As a result, a Qi-led coalition, created by the “vertical school” of the scholar Su Qin, rose along a north-south axis to defend against Qin’s frightening rate of expansion, but it was undermined by Qin’s subversion of individual states that held up the alliance, represented by the efforts of Zhang Yi’s “horizontal school.”

By the time of Ying Zheng, the anti-Qin alliance was all but powerless, whereas Qin had fought multiple successful wars on all its eastern borders while assimilating non-Chinese peoples from the frontiers. The empire was ripe for the taking.