The Legacy and Life of Margaret Olley

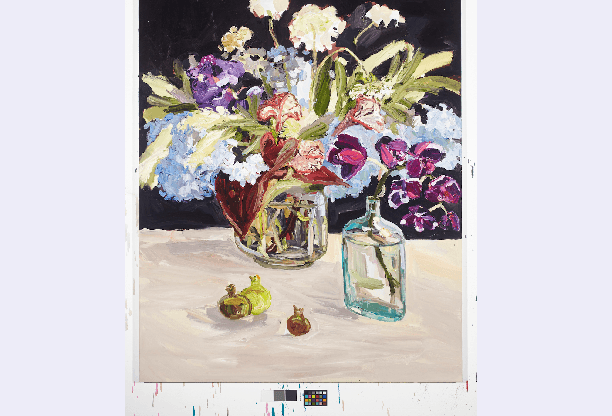

Famous for her rich and detailed still life’s, intimate interiors and occasional landscapes, and influenced by the early impressionists of Europe, she is represented in all the major institutions in Australia.

|Updated: