NEW YORK—Those supporting fast-food workers’ efforts to unionize released a report Oct. 15 drawing attention to the taxpayer costs of low wages.

Just over half (52 percent) of fast-food workers nationally are enrolled in one or more public assistance programs, according to the University of Illinois and UC Berkeley Labor Center report. By contrast, only 25 percent of the overall workforce uses public assistance.

In New York, the number of fast-food workers on some form of assistance is 60 percent.

Pulling in just $7.25 an hour isn’t cutting it for many low-wage workers. They have to rely on programs such as food stamps, Medicaid, and earned income tax credits. The safety net has become a bridge to fill the gap low wages have left. A quarter of the estimated 104,000 fast-food workers in New York receive food stamps.

The cost of government assistance for fast food workers is $7 billion per year. New York State accounts for $708 million of those costs, according to the report’s authors.

Article Continues after the discussion. Vote and comment

[tok id=9c3730b09a15c65efb53bf85a25f3d08 partner=1966]

“Those low wages have a cost, and it is sometimes a hidden cost,” said Stephanie Luce, an associate professor of labor studies at CUNY on Oct. 15.

Organizing for Change

Fast-food workers—73 percent of whom do not live with their parents, and 26 percent of whom have children—have spent much of the last year organizing in hopes of earning better wages.

Broad support for raising the minimum wage exists at the federal level, with President Barack Obama favoring the approach, but actual progress has been minimal.

A small gain, the state of New York is planning to raise the minimum wage from $7.25 to $9 per hour by 2016, an amount that will not keep up with inflation.

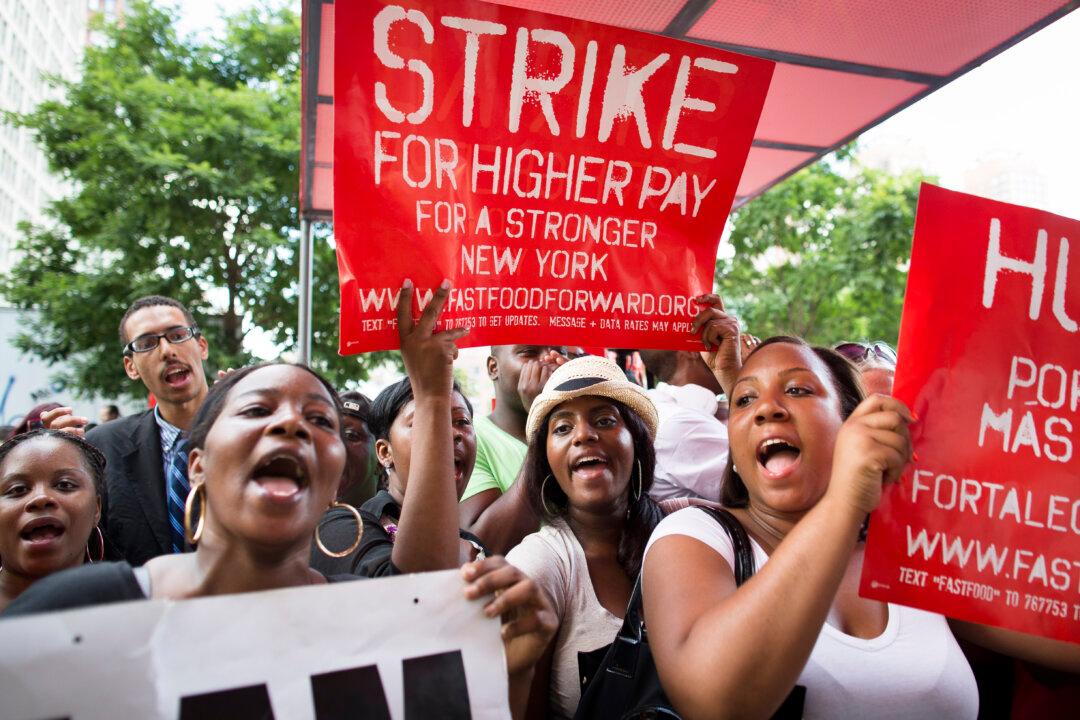

Last November, in New York City, 200 fast-food workers went on strike.

New York Communities for Change and other local community groups organized the first strikes. The Service Employees International Union (SEIU) also stepped in to help strategize and support the larger national movement to raise wages, and ultimately unionize fast food workers.

In August, the movement gained national momentum when fast-food workers in 58 cities went on strike demanding higher wages.

“Workers need to continue to build power, develop their movement, and begin to understand how to strategize in a manner that leverages a stronger response from the industry,” said the Rev. Martin Rafanan, a community organizer in St. Louis who spoke on a conference call with reporters Oct. 15.

Company Response

Fast food companies have generally balked at the idea of raising wages, claiming thin margins prevent them from doing so.

“Significant additional labor costs can negatively impact a restaurant’s ability to hire or maintain jobs,” said Katie Laning Niebaum, a spokeswoman for the National Restaurant Association, which includes the nation’s largest fast food employer McDonalds, in an email commenting on the issue this summer.

According to Luce, “there is a lot of research that shows raising the minimum wage has a positive impact for workers, but it depends on how much the wage is raised.” She added the benefit would only work if the hours stayed the same.

“Just raising the wage not a solution on its own will not eliminate poverty. But it is one piece of it.”

With additional reporting by Kristen Meriwether