LANSING, Mich.—A year after the tap water in Flint was exposed as a source of dangerous levels of lead, residents of the impoverished city are still grappling with the man-made public health crisis, which has led to criminal charges and drawn attention in the presidential election.

Doctors discovered high amounts of the toxin in children last September and warned against using the Flint River water. Local health officials declared an emergency and Republican Gov. Rick Snyder confirmed there were “serious issues” after state officials downplayed concerns despite other problems with the municipal water.

In addition to the criminal investigations, the crisis has sparked congressional hearings, lawsuits and scrutiny of lead testing across the country. Here’s where things stand today:

Is the Water Safe?

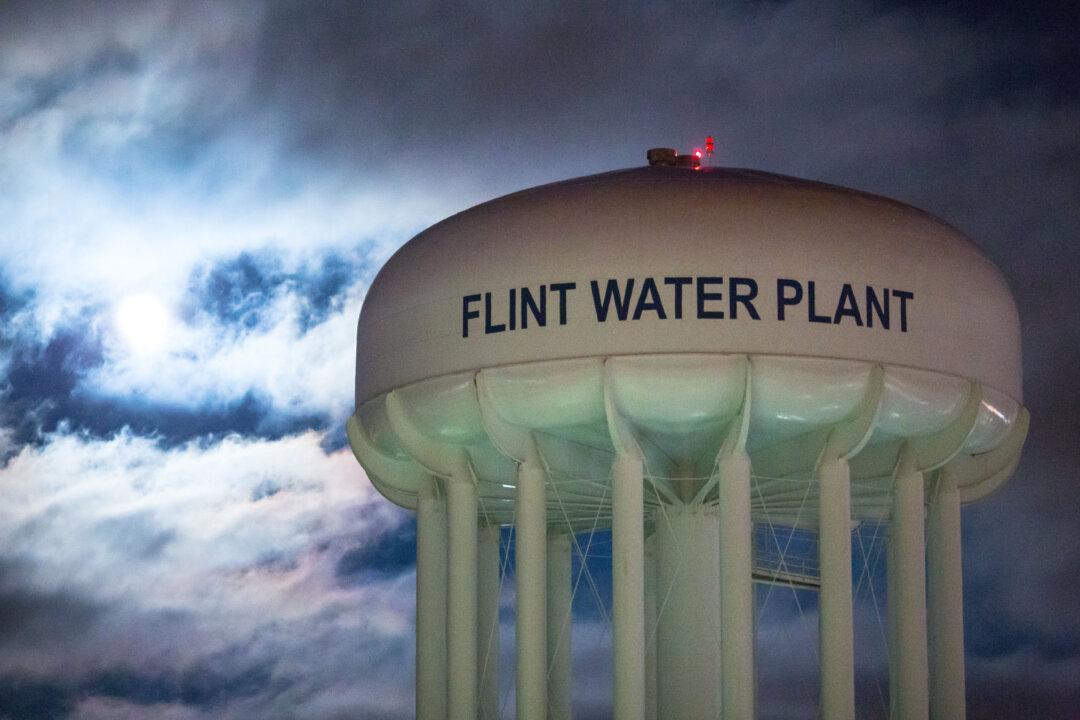

Flint, whose water source was switched in 2014 to save money while the city was under state emergency management, returned to a Detroit-area water system in October. But Flint’s 99,000 residents still can’t drink the water without a filter until the system has been made safe with corrosion-reducing phosphates, a critical step that was missing when Flint used the river for 18 months. The state is still distributing filters and bottled water at spots throughout Flint. The state health agency says the decision on whether to shower or bathe with city water “is an individual one.”