BEIJING - World Cup Soccer 2006 in Germany propels Chinese soccer fans to the pinnacle of excitement as their daily lives revolve around the games. Soccer is not China’s best-played sport, but it is the most popular one. Some analysis indicates that the enthusiasm and desire for soccer comes from a need to offset China’s position in international soccer competitions. Others believe it compensates for the lack of freedom of speech and democracy in China.

Chinese fans are crazy over this major world event. Living outside of China, people do not understand how fanatical Chinese people are. Shortly after the beginning of the tournament on June 9, there were several suicides of Chinese fans because their favorite team lost.

What is more difficult to understand is that the team that lost was not the Chinese team, which failed to even make the playoff cut. It seems that those Chinese who have always held a national animosity toward certain countries have become global citizens when it comes to soccer. Not only do they lack animosity toward the “western powers,” but they fervently cheer for the team of their choice until the end.

The act of suicide is the extreme response of only a few fans though. Most fans watched the live broadcast throughout the night during the games, that’s all. Many fans were completely familiar with every aspect of their favorite star players, like fans in other countries that have strong soccer teams. Chinese people constantly think and talk about nothing else.

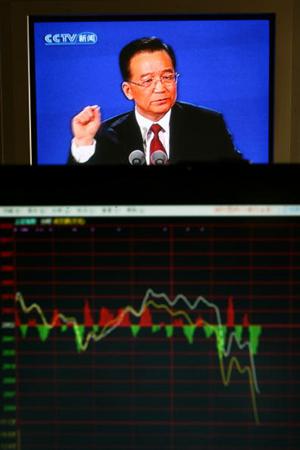

A renowned and reputable China Central Television (CCTV) sportscaster, during a recent quarter finals game between Italy and Australia lost himself and shouted out, “Long live Italy!”

How did this soccer enthusiasm begin in China? Just after the mayhem of the Cultural Revolution, mainland China began live broadcasts of world soccer games in 1978. The freshness of the games opened the souls of many in China.

Chen, a Beijing white-collar worker, and a high school student at the time said: “At that time, many people thought watching world soccer was fashionable.”

On October 18, 1981, the Chinese national team beat the favored Kuwaiti team by three to zero in the World Cup Asia preliminary tournament.

That evening, local university students’ emotions were boiling over. Youths headed by the students from Beijing and Tsinghua Universities marched in the streets, celebrating a seldom seen victory for the Chinese team. Beijing University students shouted out “Strengthen China,” which connected the ball game to a sense of the rise and fall of the country.

Chen, a People’s University student in 1981, also recalled: “We could not set off fire crackers in the apartment building area, so we threw glass thermo-bottles down the stairs because they sounded like fire crackers as they broke.

The People’s University did not allow students to participate in the rallies; the doors were locked. Unable to control their emotions, some students crawled out of the apartment windows to join the parade for this rare celebration.

Some say that the student parade that evening was the first spontaneous student movement since the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) took over in 1949. Since then, fans’ enthusiasm is growing more intense with each world cup playoff.

But the Chinese national team’s performance is not up to par with the enthusiasm of the fans. Other than the 2002 World Cup Soccer playoff held in Korea and Japan, the Chinese team has never made it to the finals.

Lin, a young writer and a big soccer fan explained, “Because the Chinese team’s performance has been unsuccessful, soccer has become an obsession. Fan’s enthusiasm and desires are directed to the Chinese team, in hope that the team would be victorious.”

He said that in the past 20 some years, China has put a lot of effort into soccer, but is unable to win the gold like it has in many other sports. He added, “For China, a major country in the world, this is hard to accept.”

On the other hand, the public doesn’t dare to express their anger at the regime or its organizations. But on the topic of soccer, they can point their fingers at the “China Soccer Association” and express their dissatisfaction and frustration without any adverse consequences.

Lin said, “The regime is probably using this relatively harmless distraction for the public to vent their growing distress over the poverty gap and pressures of life.

“It can be said that the support for any team or star player is a type of psychology compensation for the lack of democracy and freedom of expression in China.” Lin added.