A recent Internet post contrasting Chinese and American approaches to educating youngsters was hotly discussed and widely forwarded online, particularly by Chinese mothers who are eager to seek the best education for their children. The article post, titled “Surprisingly, My Son Received Such Education in America,” describes the school life of a 9-year-old Chinese boy who moved from China to the United States. It was soon reposted nearly 5,000 times on Sina Weibo, China’s version of Twitter.

“In China, his bag had been full of heavy books from first grade. From Grade 1 to Grade 4, we changed school bags three times. The next one was always bigger than the previous. We assumed that the amount of knowledge given to him was also growing,” confessed the mother, who at the beginning was rather confused about the free-spirited American teaching style.

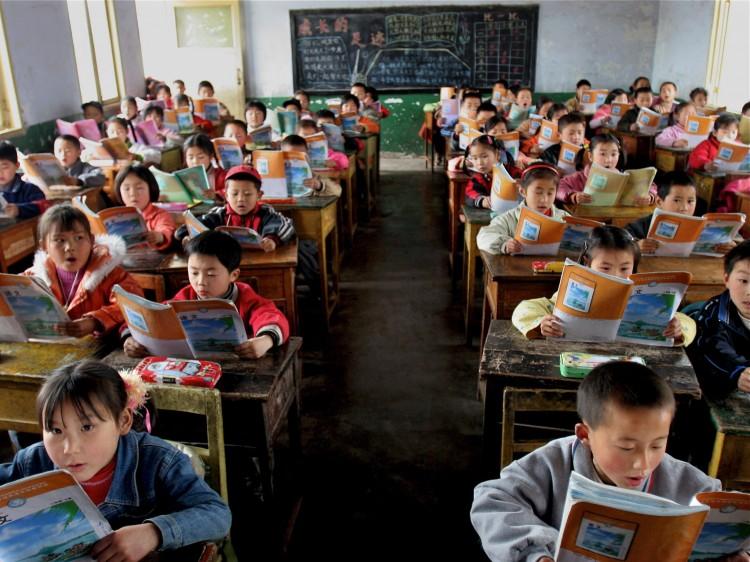

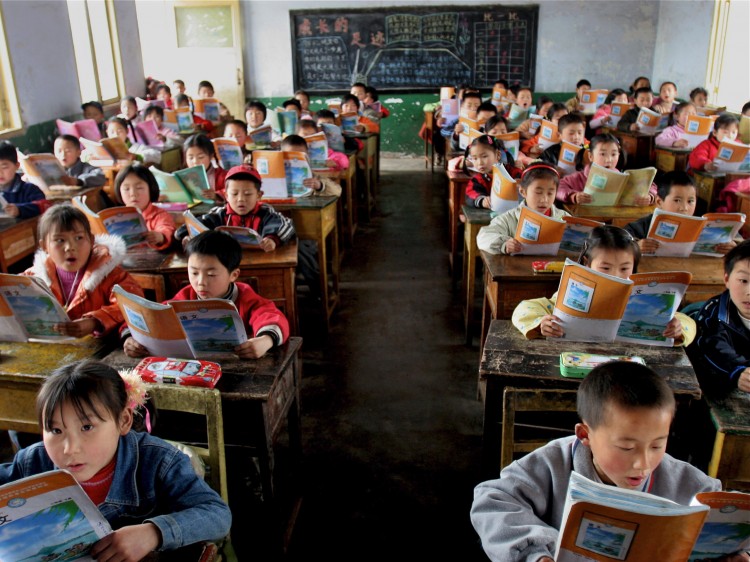

Unlike in Western countries, students in China do not have the freedom to choose what they want to learn. Chinese schools uniformly use standardized textbooks composed and published by the regime. From Grade 1, students receive one textbook for each subject, and have to carry the ones they need to school for class everyday.

But when she asked what was the best thing about going to school in the United States, her son answered “freedom.” “His words hit me like a blow to the head,” the mother wrote.

In China, individual research is rarely used at education levels before college, and students are usually given standardized answers to exercises. One day, her son brought back books from the library to work on a project which he called “the past and future of China.” She thought to herself: “Such a bold topic, would a Ph.D. candidate even dare to work on it?”

Soon the result took her by surprise. “I was stunned upon seeing his work. He separated the materials he gathered into sections and chapters, and attached a bibliography in the end. This was the writing style I learnt during grad school, and at that time, I was 30 years old,” she said in the post.

Another major difference was history class. “When I saw my son browsing through books about the World Wars with joy, I couldn’t help but think about how boring it was for me to memorize the time and detail of historic events. Even when the conclusions were obviously pedantic and wrong, I had no choice but to memorize it.”

Materials in history classes in China are often strongly propagandistic and fabricated for political reasons. A Chinese elementary textbook, available online, shows that the first long reading exercise for first graders is a 200-character passage about a prominent communist figure planting a tree. “Grandpa Deng Xiaoping attracted the eyes of many. He held a shovel in his hands and his forehead was full of sweat. But still, he would not want to take a break,” the text said.

In contrast, American teachers encouraged students to find answers to history themselves, the mother wrote. “Teachers are expressing the idea of humanism through questions, and they help them to pay attention to the fate of human beings. They teach the kids ways to tackle big questions. There are no standard answers to these questions, and some of them require someone to use his or her whole life to search for the answers.”

“I always think about the way elementary students work in China. They sit with their backs straight, carry heavy books, spend hours on homework and do their best to pass the rigid exams,” she wrote. “It gives us a huge sense of pressure and oppression.”

The Epoch Times publishes in 35 countries and in 19 languages. Subscribe to our e-newsletter.