According to tradition, Chinese New Year celebrations continue until the Lantern Festival, which falls on the 15th day of the first month on the Chinese lunar calendar.

On the Western calendar, the Lantern Festival this year takes place on March 5, marking the end of more than two weeks of festivities that began on Chinese New Year’s Day on Feb. 19.

The Lantern Festival is traditionally marked by lantern displays and other activities that pay reverence to the divine, and by making and eating small, round dumplings that symbolize family togetherness and happiness.

The Lantern Festival is also called Yuanxiao Festival, or Yuan Xiao Jie (元宵節, yuán xiāo jié), where 元 (yuán), literally “first,” indicates the first month; 宵 (xiāo) refers to night; and 節 (jié) means festival.

The Yuanxiao Festival is also the first time for the full moon to appear in the new year.

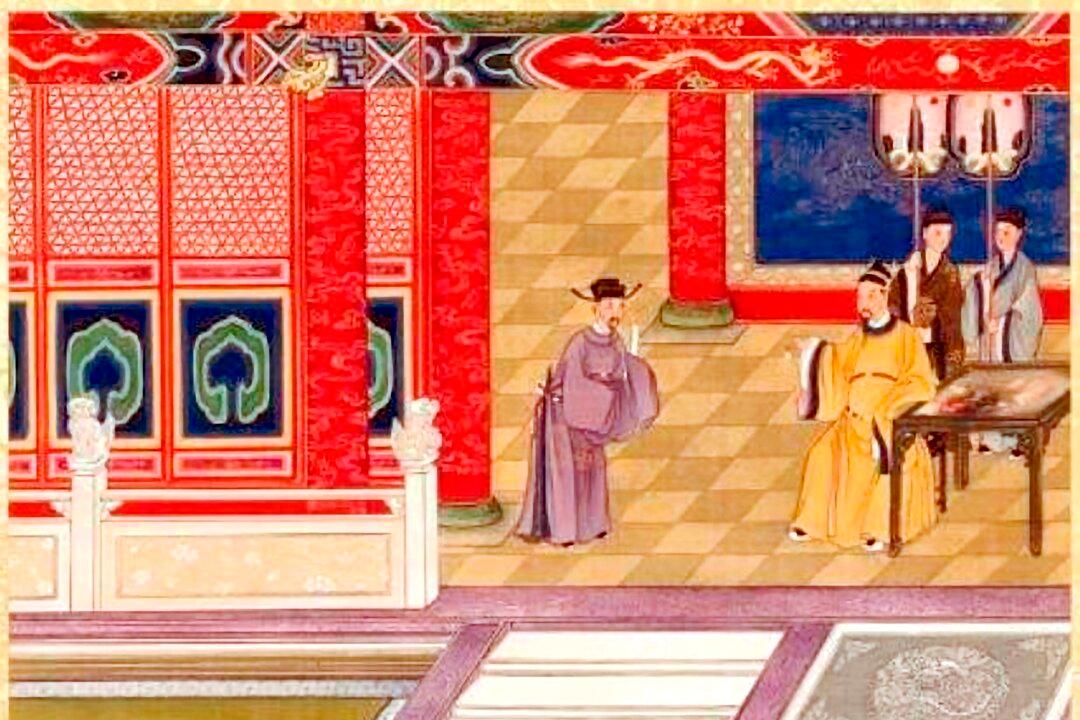

‘Official of Heaven’ Bestows Good Fortune

There are many stories about the origin of the festival. One comes from the time of Qin Shihuang (259–210 B.C.), who was the first emperor to unite the country after conquering all the other feudal states at that time.