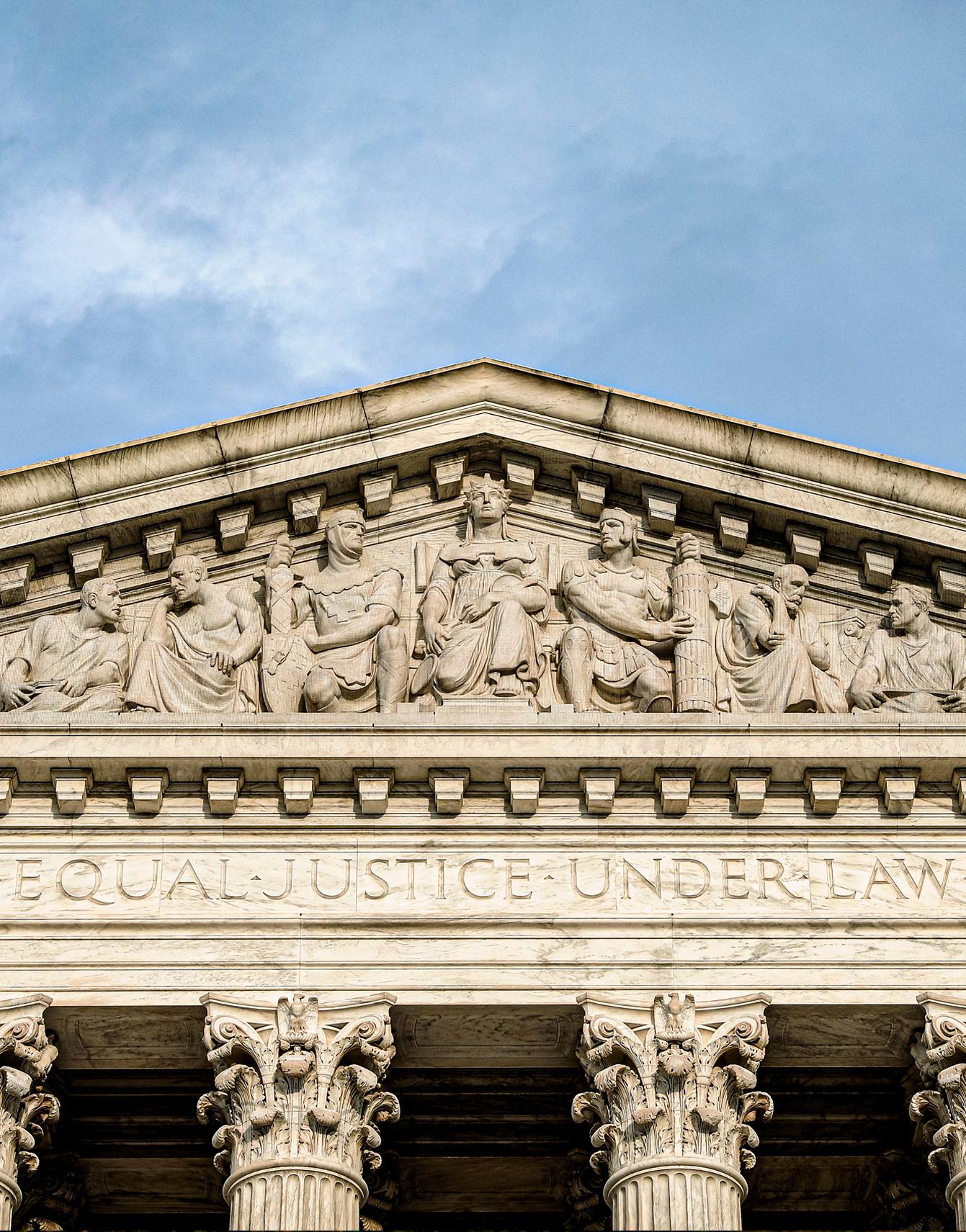

The Supreme Court made a wave of historic decisions in 2024 on topics ranging from presidential immunity to social media and ballot disqualification.

The presidential election combined with rising administrative law disputes helped tee up controversies that put the court and its decisions in the spotlight. Those decisions created rippling effects for other cases and how entire branches of government are expected to make decisions.