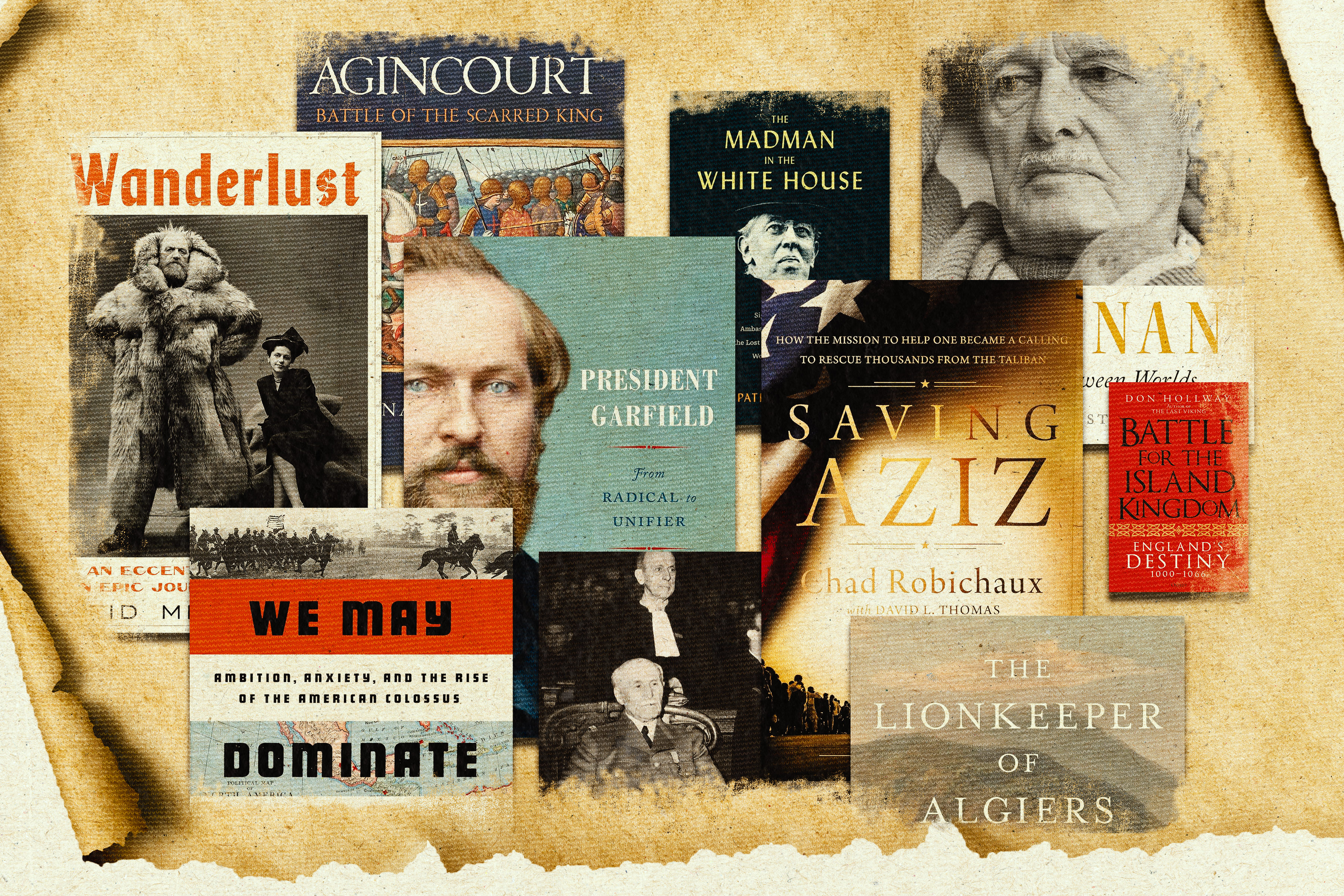

This year, I wrote more than 40 reviews of history books, on some good, some better than others, some a chore to finish, and some so wonderful they belong in my top five. From ancient history to modern history, from biographies to memoirs, from wartime to peacetime, these are the five that were the best written, most thoroughly researched, and most memorable. I have assembled five other honorable mentions that were too good to leave off the list completely.

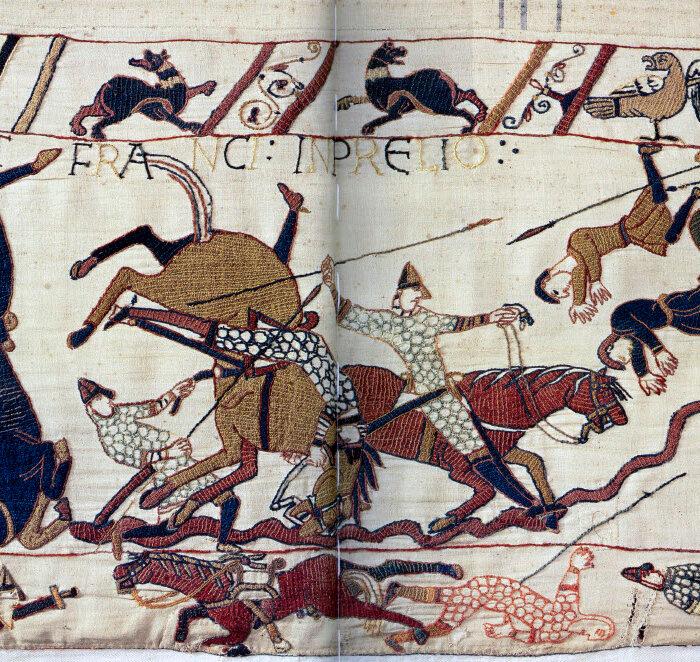

5. ‘Battle for the Island Kingdom’

Ruthless, vengeful, traitorous, brutal, and pious—it all sounds so medieval. And this is precisely the era in which author Don Hollway does such great work. His third book is a bloody and violent triumph, as it takes readers briskly yet thoroughly through the decades leading to the Norman invasion of England and the famous Battle of Hastings in 1066. With the ultimate climax to this story—a year that ended with three famous and incredibly consequential battles—this book seamlessly ties in many storylines ranging from England and its earldoms to Normandy and France to the Vikings of Scandinavia. All seem to be vying for the crown, and those who aren’t eligible still work tirelessly and ruthlessly to help their “candidate” secure the throne.

4. ‘Kennan’

George Kennan is remembered as one of the United States’ greatest diplomats and arguably the most consequential of the 20th century. He is credited with devising President Harry Truman’s foreign policy doctrine of containment against the Soviet Union, which remained in effect throughout the Cold War. Although Kennan is most remembered for his “long telegram,” the singular 5,000-word transmission that described the policy, there is so much more to him.

Frank Costigliola presents the diplomat as a nuanced, intriguing, sometimes cold, and brilliant workaholic. The author demonstrates that although the telegram was his most influential work, it wasn’t his favorite, and he eventually regretted writing it. The author weaves together Kennan’s family life, his professional life, and his love-hate relationship with Russia, a relationship with all the markings of a love affair destined to end tragically.

3. ‘President Garfield’

Considering his term in office was cut tragically short—to only 200 days (and half of those were spent with him trying to recover from an assassin’s bullet)—the lack of attention that James Garfield has received from historians is self-explanatory. C.W. Goodyear has made up for much of that dismissal, and his biography of the 20th president proves that Garfield shouldn’t be dismissed.

Pulling from countless contemporary sources, from journal entries to letters to congressional minutes to newspaper clippings, the historian paints Garfield as a man most desired for public office: honest, sympathetic, and principled. For such a relatively young historian, Mr. Goodyear’s gift of precise yet exhaustive storytelling that holds the reader’s attention is at a level one would expect from a highly seasoned biographer.

2. ‘France on Trial’

The life story of Philippe Pétain has humble beginnings, transitions into a meteoric rise as a national hero of World War I, and then plummets into villainy. Pétain’s reputation found itself among the rubble of World War II’s aftermath, when he became the face of the Vichy government and remained so until the end of the German occupation.

Author Julian Jackson presents a man whose firm belief in the justice and rightness of his own actions led to his downfall—and he does it all during Pétain’s treason trial. The British historian, whose niche is World War II France, masterfully uses the trial as a literary device to tell the story of not just the trial, but also those years that preceded it, the decisions Pétain made as the Vichy leader, the repercussions of those decisions, and how his actions put not only himself and those in the government who collaborated with the Germans on trial but also, as is clear from the title, all of France.

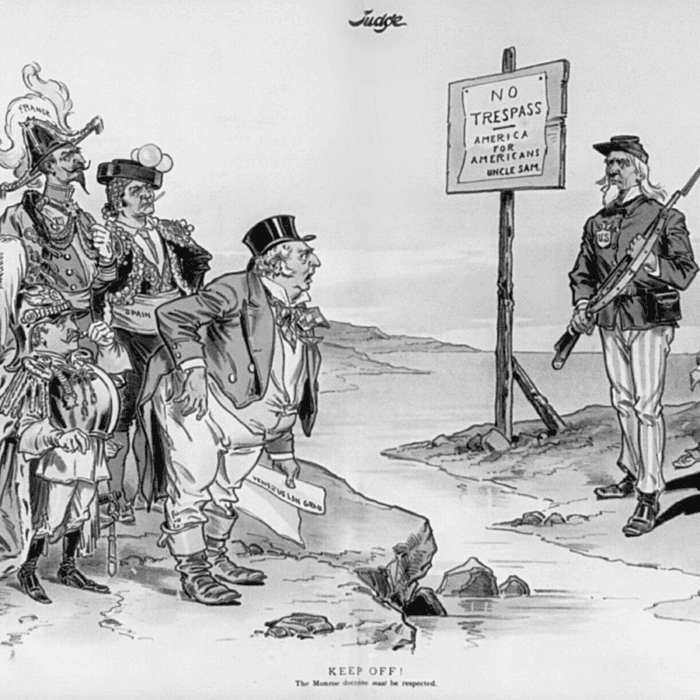

1. ‘We May Dominate the World’

I usually read several books at a time, but shortly after I began “We May Dominate the World,” I put aside all other reading. Sean Mirski, in his debut work, displayed the skill and creativity of a veteran at the top of his game.

The author utilized a collection of foreign relation stories ranging from Napoleon III’s affront to the United States in Mexico to the liberation of Cuba to the construction of the Panama Canal in order to explain the methods, the reasons, and the anxieties behind the United States’ foreign policy decisions in Latin America from the Civil War era to the Gilded Age through to World War II.

Mr. Mirski pored over sources from numerous administrations, their diplomats, political allies and critics, and Latin American leaders in his eight years of research (his notes section at the end of the book is appreciatively lengthy) and used these varied perspectives extensively and never without good purpose.

Honorable Mentions (In No Particular Order)

‘Saving Aziz: How the Mission to Save One Became a Calling to Rescue Thousands From the Taliban’

‘Agincourt: Battle of the Scarred King’

‘Wanderlust: An Eccentric Explorer, an Epic Journey, a Lost Age’

‘The Madman in the White House: Sigmund Freud, Ambassador Bullitt, and the Lost Psychobiography of Woodrow Wilson’

‘The Lionkeeper of Algiers: How an American Captain Rose to Power in Barbary and Saved His Homeland from War’

Through high-seas adventure, torturous imprisonment, and tactful, candid, and calculated decision-making, a young sea captain finds his place in the lore of early American heroes.